© Steve Cary, February 21, 2024

With winter receding in our rearview mirrors, it is past time to lay out some fun projects and goals for the 2024 season. In doing so, I want to draw attention to our state’s northwest quadrant, where new things turn up regularly and many questions remain to be answered because few of us spend any time there. If you have your own 2024 goals and objectives, that is terrific and more power to you. But if you’re scratching your head about what to do this year, please consider Northern Azure and Julia Orangetip, which I’ll discuss below. But first this message:

The US Fish and Wildlife Service recently published in the Federal Register the listing rule for the silverspot butterfly as “threatened” with a 4(d) rule. The news release is here: https://www.fws.gov/press-release/2024-02/silverspot-butterfly-receives-protections-under-endangered-species-act. The news release has hyperlinks to a PDF version of the Federal Register document and to the Species Status Assessment. The SSA can also be found on the following ECOS website along with other documents including the Recovery Outline: Species Profile for Silverspot (Speyeria nokomis nokomis) (fws.gov). The recovery planning process is expected to begin later this year.

For butterflyers, one extraordinary blessing of living in New Mexico is the abundance of public lands that can be accessed for butterfly appreciation purposes. Federal lands managed by the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are a huge part of that asset, but the State of New Mexico also manages a lot of land we can recreate on. Lands managed by New Mexico State Parks, New Mexico State Land Office, and New Mexico Department of Game & Fish can be accessed legally with annual permits or licenses for which only nominal fees are charged.

- New Mexico State Parks $40 annual day use pass here: https://newmexicostateparks.reserveamerica.com/

- New Mexico State Land Office $35 recreational access permit here: Forms & Applications | NM State Land Office (nmstatelands.org)

- New Mexico Department of Game and Fish licensing is here: Welcome – NMDGF (state.nm.us). I usually add on donations for the Department’s wildlife education and habitat management programs, so your costs may vary, but they are in the same ballpark as the other two.

Orangetip Detectives. If you get your permits in-hand in the next few weeks, you’ll be ready to help figure out the orangetips in northwestern New Mexico. Two species seem to converge there: Southwestern (Anthocharis thoosa) and Rocky Mountain (Anthocharis julia) (see below). I suspect we transition from Southwestern Orangetip to Rocky Mountain Orangetip somewhere between Heron Lake and the Colorado border, but neither species is documented very well in Rio Arriba or San Juan counties. Data are sparse and you can help remedy that. Good places to look include Humphries Wildlife Area, Sargent Wildlife Area, Rio Chama Wildlife Area (all New Mexico Game & Fish Department GAIN properties), as well as Heron Lake State Park, and Carracas Mesa, which is in the Dulce Ranger District of the Carson National Forest.

April is the month to be out there. Male orangetips like to patrol hilltops within piñon/juniper woodlands, so modest summits below 8500 ft are good places to check in mid-April. For example, on Carracas Mesa they fly on Mesteña Peak, 7700 ft, which you can drive to if road conditions permit. At Humphries WMA they fly on Tecolote Rim, 8100 ft, about a two-mile hike south from the parking area on US 64 west of Chama. At Heron Lake State Park, I saw one orangetip last year in the pygmy ponderosa pine forest on the Rio Chama rim (~7200 ft). Late in the flight season (early May) look for females nectaring at and placing eggs on native mustards. For identification purposes, photographs of undersides are most helpful because ventral marbling is dark green on Southwestern Orangetip but gray on Southern Rocky Mountain Orangetip. Feel free to reach out to me if you need more information or encouragement.

Adding the Northern Azure to Our Butterfly Fauna. Butterflies of New Mexico co-authors Mike Toliver and I, in consultation with Colorado’s Mike Fisher (2009) and after review of work by Colorado’s late, great Jim Scott (2022), have concluded that New Mexico has at least two different species of Azures. And one of those has two subspecies in NM, so actually we have three distinguishable azures. What can I say? Life and Nature are not simple!

Here are the three:

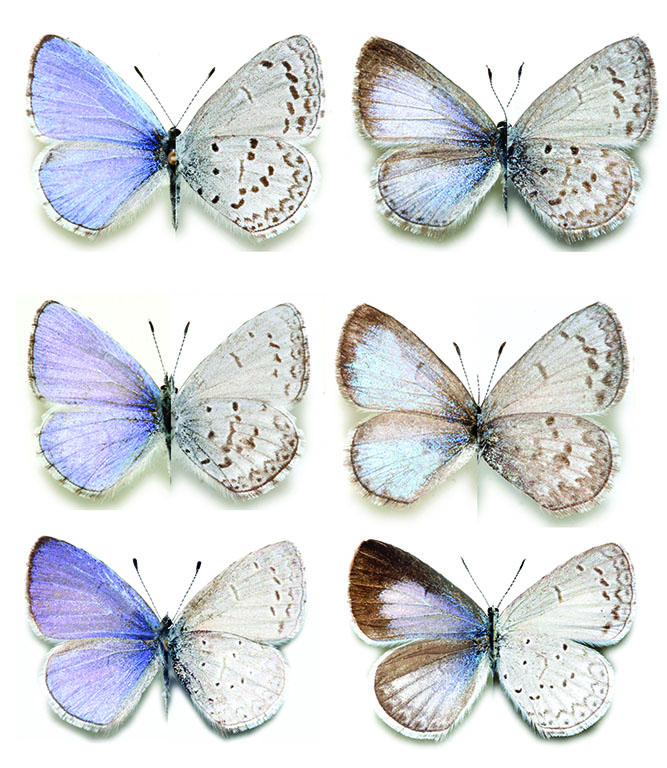

Mike’s figure shows you almost everything you need to know to tell one from the other two. Nevertheless, let a me add a couple paragraphs of interest. [I can’t help it; I like words.]

‘Gray’ Echo Azure (Celastrina echo cinerea) is widespread in New Mexico, occupying all of our counties except in the Eastern Plains. It seems to be the only azure to be found south of I-40. It flies in two or more generations per year, mostly spring (April – June) and summer (July – September). The Plate’s bottom row shows that ‘Gray’ Echo Azure is lightly marked underneath, with a whitish ground color and with marks that are small and gray, as if the printer was low on black toner. Wing fringes are white and have black checks that are weak (forewing) to absent (hindwing). Dorsally, males are iridescent blue with a thin black marginal line that swells near the FW apex. Females also are silvery blue above, but the forewing blue is reduced in coverage and bounded by a broad black submargin that dominates costal and postmedian areas.

Northern Azures (Celastrina lucia ssp.) occupy the top two rows of the Plate. Geographically they are ‘northern’ and in NM that means our north-central mountains, where one also can find Echo. Northern Azure typically has one flight per year and that is in spring (May-June). Northern Azures are more heavily marked underneath than Echo; males (left) have gray/white ground color not much different from Echo males, but the spots and chevrons are larger and darker, showing plenty of toner in the cartridge. The female Northerns (right) have a rather grizzled look to the ground color and the spots and chevrons seem rougher, imprecise, perhaps a tad smeared. Wing fringes, too, seem a bit smeared; they are white to gray with heavier black checks than Echo; forewing checks are heavier than hindwing checks. Dorsally, the male is iridescent blue, alleged by Scott to be less “violety” than on Echo. For me, that iridescence seems so dependent on light angle, viewing angle, and physical wear that I do not count on that as a diagnostic character. Instead, look to the forewing submarginal black, which on females is much restricted compared to Echo.

The foregoing paragraph applies to both Northern Azure subspecies sidara (top row) and subspecies lumarco (middle row). How does one distinguish between the two subspecies? For now, I do it geographically. The Sangre de Cristos (east of the Rio Grande) seems to have the most prominent and precisely defined ventral spotting (sidara) while the Jemez (west of the Rio Grande) seems to have lumarco. We have not yet examined enough specimens or photographs to be 100 percent certain, but that is the preliminary indication. Honestly, there is overlap in ventral hindwing spotting “densities” between the three Azures. And of course, wear and odd photo angles can render some observations undeterminable.

Furthermore, there is a wildcard in this game. Northern Azure seems particularly prone to unusual ventral hindwing patterns which would be deemed aberrations if they were not so frequently seen. These oddballs occur in up to half of the adults in some parts of Colorado and are sufficiently routine that they have names. They are less frequent in New Mexico, but the names still apply: the blotchy black median area = form lucia; extra black marginal chevrons = form marginata; when both are present = form lucimargo. These various forms occur in both subspecies sidara and lumarco, but more frequently in the latter. Hence, they are merely infrequent in the Jemez, but quite rare in the Sangre de Cristos. They are not known to occur in Echo Azures at all.

We still have much to learn about azures in NM, particularly about Northern Azures. I invite you to do some of your own sleuthing, some photography, and sharing of observations to your favorite citizen science web platform. Much more data are needed to be sure: we have essentially zero data from Mt. Taylor and none from the Tusas Mountains. How can Northern not be there? Dick Holland documented Northern Azures in the Chuska Mountains, but that was 40 years ago. Please go to those places and bring back information. The ideal observation has dorsal and ventral images of the same individual. I realize that’s asking a lot, but the hard-to-get female dorsum shows the most persuasive diagnostic marks, and the iridescent blue makes it all worthwhile.

References Cited

Fisher, Michael S. 2009. The Butterflies of Colorado: Riodinidae and Lycaenidae – Part 4: The Metalmarks, Coppers, Hairstreaks and Blues. Lepidoptera of North America 7.4. Contributions of the C. P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Colorado State University. Fort Collins. 205 pp.

Guppy, C. S. & J. H. Shepard. 2001. Butterflies of British Columbia. Including western Alberta, southern Yukon, the Alaska Panhandle, Washington, Northern Oregon, northern Idaho, northwestern Montana. Royal British Columbia Museum, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver Toronto, 414 pp.

Scott, James A. 2022. Butterflies of the Southern Rocky Mountains Area, and their Natural History and Behavior. Papilio (New Series) #27 March 2022. ISSN 2372-9449. {Text only. See Papilio (New Series) #28, 29, 30, 31 for photos}

Thank you Steve. I enjoyed the pictures. Looking forward to see the Orange tips in April come to our Cherry bush blooms.

Thank you for all the fascinating and helpful information, Steve. Are there any groups that organize hikes to help identify and report our butterflies? I’m a novice and would like to learn from others.

Thanks Steve, always fun to read about what to look for when the warm weather arrives.

I was surprised to read in an article in the Carlsbad Current Argus that the Nokomis Fritillary is thought to to only exist on private land in New Mexico. I will redouble my efforts in the Fall to find it in the Gila. Dr. Zimmerman noted its presence in the highlands but theorized that fire damage & development have extirpated them.

Steve…glad to see you got your peecnature sight back up again. Good generalization on NM Celastrina lucia and echo. A couple of things to correct…

1| The lucia lumarco form with the blotch in the central uhw is lucimargina not “lucimargo” (I was thinking…isn’t your wife’s name Margo or maybe I am mistaken?…if so, that would be easy to understand that error!).

2| Photo opposite ‘Front Range’ Northern Azure you have also name “Northern Azure” from the Jemez Mts. is an aberrant and likely C. echo based on the September date.

3| C. lucia lumarco is found in the Chuska Mts…Holland had specimens Scott examined…his collection as you know is in the CSUC

Gillette Museum in Fort Collins, Colorado.

I forgot to include in item 1| of the post…lucimargina is the form with the blotch in the central uhw AND darkened marginal border…just to clarify.