© Steven J. Cary, March 31, 2024

By the time you read this, winter will be over, at least from a calendar perspective. What the weather does, however, is a completely different matter. Nevertheless, I hope your winter went well, whatever that means for you. As for me, I am looking forward to good butterflying in 2024. In this month’s blog we have two stories. Before we discuss Summer Azure, I encourage you to get comfortable, to sit back and enjoy a brief but productive guided safari by Jim Von Loh . . .

Butterflies are slowly starting to appear! story and photos by Jim Von Loh. On March 11, I visited a short segment of Sotol Creek near the Pine Tree Trail, east of Aguirre Springs Campground, on the east-facing slope of the Organ Mountains, Doña Ana County. A few Ornate Tree Lizards (Urosaurus ornatus Baird & Girard, 1852) were perched on sun-warmed rocks along the drainage and hunting insects visiting the moist sand, so I sat for about 45 minutes near them and photographed moths and butterflies landing on the moist sand. Typically, the hunting lizards moved slowly (sometimes jumping from rock-to-rock) until seeing prey, made short stalking runs towards the prey, then burst into a quick run for the ambush/capture.

Do we need an epitaph here? As sad as it is to see a lovely hairstreak gobbled up, it reminds us that insects were designed to be eaten. The insects’ reproductive strategy: offspring get little to zero care, but overwhelming numbers ensure that some survive. Not very romantic is it?

The Pleasures of Azures, by Steve Cary, Andy Warren and Mike Toliver. In a recent blog post (Feb. 2024), Steve confidently introduced readers to Northern Azure (Celastrina lucia) which had not previously been reported from NM. Well, that announcement may have been premature. The azures (Celastrina spp.) are a complicated group whose members can be difficult to decipher, and Steve readily admits that he dove headlong into taxonomic waters warranting a more cautious and studied approach. Announcement of Northern Azure in New Mexico triggered a detailed response from Andy Warren, who is of the opinion that neither we nor Colorado have Northern Azure. Mike T., Andy and I discussed the matter over a few emails, eventually agreeing we needed more information about azures in New Mexico before we could draw any well-supported conclusions.

When it comes to publicly available information, the photographs of Celastrina species in BAMONA and iNaturalist are great resources. However, many observations on those platforms show only a dorsal or ventral surface; focus and lighting are sometimes issues, as well. As a result, quite a few observations are not confidently determinable to species. In comparison, properly curated physical specimens allow a researcher to examine each individual’s upperside and underside in the same light conditions. An excellent assortment of New Mexico azures reside in a curated collection housed at the Gillette Museum at Colorado State University (CSU) in Fort Collins. Being only a two-hour drive away, and it being mid-winter, Andy generously volunteered to go look things over and take photos where needed. Much of the discussion that follows in this and future Azure posts (yes, more are coming), hinges on Andy’s work with about 500 CSU Celastrina specimens collected by our dear late colleagues, Richard Holland and Ray Stanford. *Our huge thanks go to Chuck Harp for providing access to Celastrina specimens in the Gillette Museum at Colorado State University.* Andy also worked with relevant Celastrina specimens from his personal collection.

Today we begin with the easy one: Summer Azure (Celastrina neglecta). It never occurred to the two New Mexico-focused authors (Steve & Mike T.) to consider Summer Azure a potential member of the New Mexico butterfly fauna. It’s an eastern species that Mike T. sees regularly near his Illinois home. If only we had read Mike Fisher’s account of Summer Azure in Colorado (2009: 111). Said Mike F.: “summer [Celastrina] blues recorded in eastern Colorado away from the foothills of the Front Range most likely represent this blue [Summer Azure]. They never seem to be very commonly encountered. Perhaps it occurs more consistently along the stream and river courses of our eastern lowlands, hot places in the summer which are infrequently visited [by lepidopterists]. Westward to near the foot of the mountains, this blue has been found very sporadically at best.” And one last bit: “I have seen no males of this blue from Colorado, only females.”

Andy, who grew up chasing butterflies in the foothills around Denver, immediately recognized it in the Gillette Museum specimen drawer. Below are photos he took of the New Mexico specimen, a heretofore unrecognized state record, collected by Richard Holland in August 1997. Said Andy: “If you get a chance, check out Mike Fisher’s writeup of neglecta. I pretty much agree 100% with everything he says there, including mostly ragged females being encountered . . . Most years neglecta is not seen in the Denver area, but some years they make it in.” Now you tell us. And apparently they can make it into northeastern New Mexico, too!

Summer Azure female (Celastrina neglecta) dorsal and ventral, Clayton Lake State Park, 5200 ft elev., Union Co., NM; August 4, 1997 (collected by Richard Holland; photos by Andy Warren; Gillette Museum, Colorado State Univ.

Summer Azure female (Celastrina neglecta) Rock Creek Cyn., El Paso Co., CO; August 21, 1990 (collected and photographed by Andy Warren)

Summer Azure male (Celastrina neglecta) dorsal and ventral, Chimney Gulch, Mt. Zion, Jefferson Co., CO; August 10, 1999 (collected and photographed by Andy Warren)

The above images should convey that Summer Azure is bleached rather white ventrally, with black marks very reduced in number and size. Uppersides also have a bleached look; notably, hindwings of males and females are overscaled with a wash of silver/white, which on males is arranged in well-defined whitish streaks between the blue wing veins. No other New Mexico azure has those qualities. Summer Azure also can be distinguished from most other azures by its late summer flight. It does have a spring brood in the East, but to date its western appearances have all been in late summer. It’s a bit weird, don’t you think? A butterfly that lives and breeds in the East and in tallgrass portions of the Great Plains, then the occasional female straggles westward, upstream, uphill, and into the prevailing westerlies. Andy says 1990 and 1993 were good years for C. neglecta in eastern Colorado. Perhaps it’s a combination of unusually good breeding conditions in certain years, producing a large population whose females then disperse more than usual in search of mates or hostplants. Finally, we refer you to the new species account for Summer Azure at Butterflies of New Mexico.

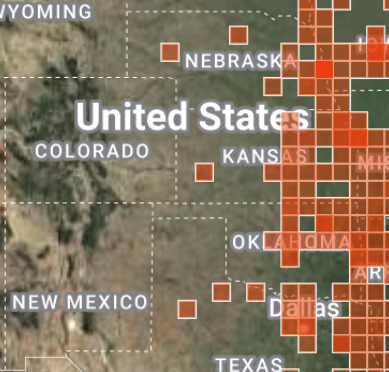

Prior to us undertaking this excavation of old New Mexico and Colorado azure specimens, iNaturalist’s map of Summer Azure in the western Great Plains looked like this March 15 screengrab by Mike T. (below left). It shows a distribution that is densest in the East and thins to the West, with peripheral westernmost observations in western Nebraska, Kansas and Texas. BAMONA shows archival records for eastern Colorado, but nothing in New Mexico.

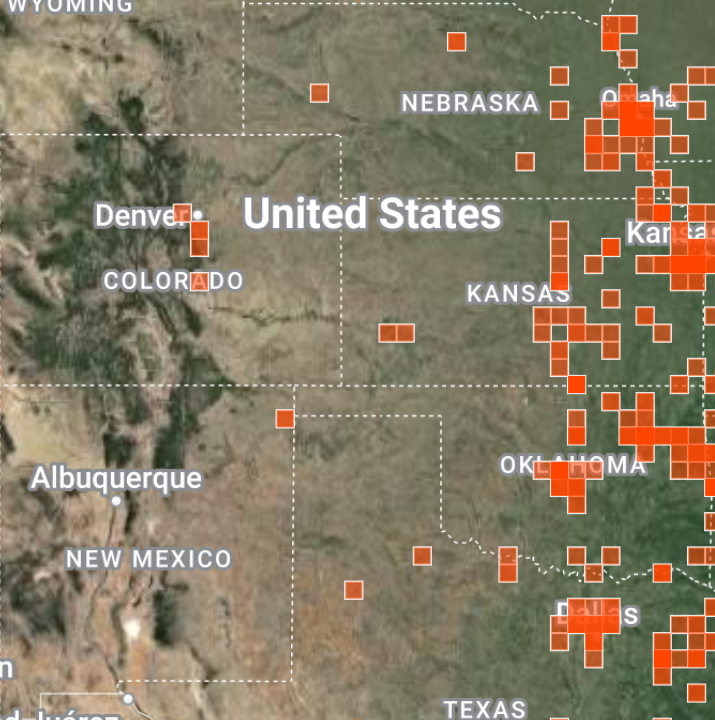

Andy’s recognition of the Summer Azure from Clayton Lake prompted him to dig up his own Summer Azure specimens from Colorado. On March 15, we posted them all (Colorado and New Mexico) to iNaturalist, then “agreed” with each other’s identifications. Now, when you search iNaturalist for Summer Azure in the USA, the mid-section of that map looks like this (above right).

While Summer Azure is a fine addition to New Mexico’s butterfly fauna, we’re not going to recommend you go looking for it in New Mexico (or Colorado) because it has been so rarely encountered here. However, if you want to maximize your odds of seeing it, we suggest you investigate the Dry Cimarron and Canadian River valleys and other east-flowing drainages in northeastern New Mexico during late July and August. Yes, it will be hot, but it might be worth the effort.

Over the course of the next few posts, we will lay out in more detail what New Mexico’s Celastrina world looks like, at least in our opinion. Please tune in next month for that and other stories.

Finally, here is a link to a great NYT article from March 30: When I Became a Birder, Almost Everything Else Fell Into Place https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/30/opinion/birding-spring-merlin-ebird.html?smid=nytcore-android-share&ugrp=c&pvid=3cc41ed5-72c6-48a5-80c7-2501d277caba

Jim’s photos are a great documentation of predation on butterflies. This is rarely photographed or reported, despite the fact that predation seems to be one of the driving forces of butterfly evolution.

Thanks, Mike – there are so many butterfly predators it can boggle the mind. Memorable encounters I’ve had included a leopard frog, a red-winged blackbird, and a few roadrunners. I’d say the most efficient arthropod predators I’ve encountered so far (with representative photo documentation) include robber flies, mantis, and dragonflies. Birds are likely the top butterfly predators and spiders should also be considered…

I’ve also seen most of those (we don’t have many Roadrunners here in C. IL). Ambush bugs are a big threat here. I’ll try and share a picture of a Monarch serving as lunch for a Green Darner.

I’ll post it on iNat – from Florida.

Sad to see my favorite Juniper Hairstreak disappear!

I have a not very good picture of a spider dragging off a painted lady at a flower barrel in Raton.