© Steve Cary, November 20, 2025

Mike Toliver authored our featured story this month, see below. But first I want to mention a little about who was on-the-wing this past month or so. Many of you recorded American Snouts penetrating farther north than usual this autumn. A couple weeks ago at the Randall Davey Audubon Center in the foothills east of Santa Fe, I observed two or three motoring determinedly northward through the gardens about three feet off the ground. You can see iNaturalist sightings in Taos and Raton, as well as along the Colorado Front Range as far as Fort Collins. Northward dispersal is far easier out on the plains than it is in rugged mountain terrain.

Monarchs also have been seen on their southbound autumn migration. On the sunny, but very windy afternoon of October 8, Marcy and I were setting up camp at Clayton Lake State Park (Union County), where we aimed to see the famous dinosaur trackway. A Monarch was positioned on the lee (north) side of a big juniper, flapping vigorously to make headway south, but the stiff wind always rebuffed it back into the shelter of the juniper. Later that afternoon after we were set up, we walked along the south lake shore. Approaching a patch of cottonwoods, we watched a Monarch deftly fly up under a low cottonwood canopy, fold its wings and disappear. Over the next 30 minutes we saw 4 or 5, apparently finishing their flight across the lake, and heading into the shelter of the cottonwoods, where they would call it a day and roost for the night.

Monarchs were still making their way south across our Eastern Plains more than a month later when Allie Arning snapped this one at Ute Lake State Park on November 14.

If you check maps at iNaturalist.org and journeynorth.org, you can get a sense of what has been happening in NM, but also the greater context of the main Monarch flight corridor, which has been mostly east of NM, as it is most years. My friend Karen recently shared this link – First GPS-tracked monarchs reach Michoacán winter sanctuary – which I’m sure you will find fascinating. Barry discovered you can download the Project Monarch app and see where GPS-tagged Monarchs have been spotted. Tagging Monarchs is not like it used to be!

A Blast from the Recent Past – by Mike Toliver

I’ve been working to update maps in our BONM website, and so I downloaded all the records from iNaturalist and Butterflies and Moths of North America for 2024 (we last updated most of the maps in 2023). As I worked on this, it occurred to me that a summary of the 2024 season might be of interest to you.

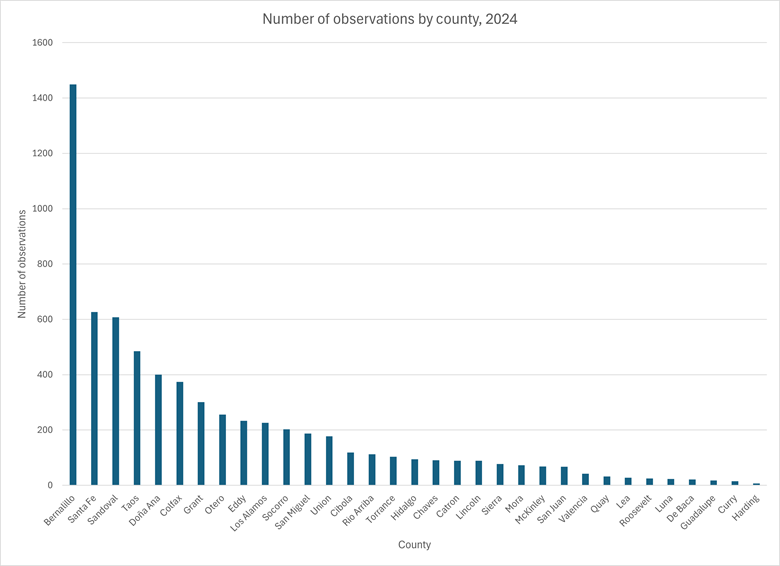

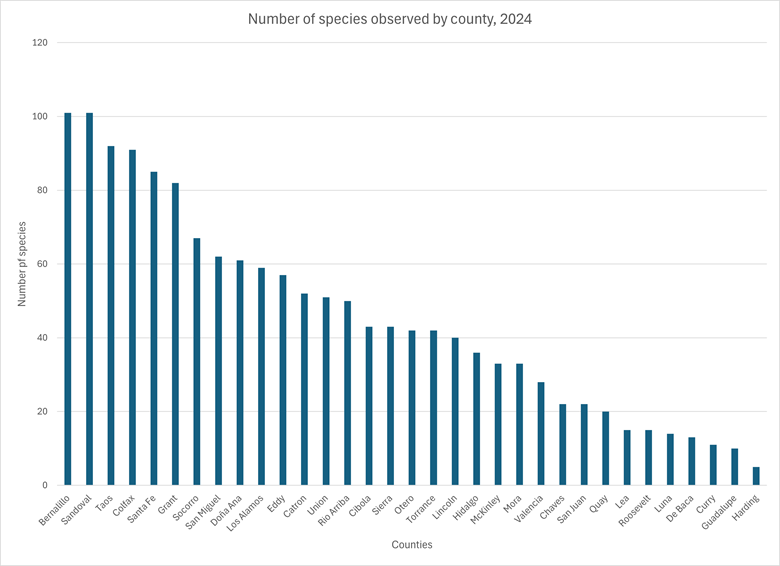

First of all, you folks observed and reported 245 different taxa (species and subspecies), representing about 52% of the known or suspected butterflies from New Mexico. Two of those, Microtia elvira – the Elfoid Checkerspot, and Eurytides marcellus – the Zebra Swallowtail, were new finds for the state (see https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/244221258 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/276090388). To accomplish this, you made and reported 6719 total observations in all NM counties. Not surprisingly, the county with the highest number of observations was Bernalillo, given that county has the largest number of observers. Bernalillo and Sandoval counties tied for the most taxa observed (101). Our eastern counties had the fewest observations – a shame because I suspect there’s treasure there!

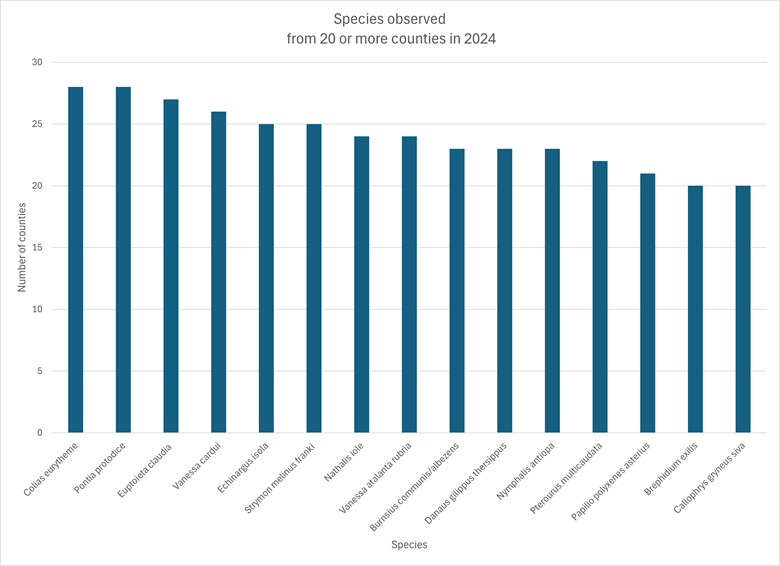

The Checkered White was observed the most (225 observations in 28 counties), with 60 species being observed only once. Four species (Pygmy Blue, Reakirt’s Blue, Dainty Sulphur, and Sleepy Orange) were observed throughout the year. The Pygmy Blue showed up on January 5th and the Dainty Sulphur said goodbye to 2024 on December 30th.

There were 15 species reported from 20 or more counties; I suspect you won’t be surprised at which species those are:

Conversely, 60 species were observed from only one county. Most of those species were observed 5 times or less; a notable exception was the Capitan Mountains Fritillary which was observed in Otero County 33 times.

| Species | No. of records | No. of counties | County |

| Amblyscirtes oslari | 3 | 1 | Bernalillo |

| Eurytides marcellus | 1 | 1 | Bernalillo |

| Heliconius charithonia vazquezae | 1 | 1 | Bernalillo |

| Argynnis nokomis | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Atrytonopsis lunus | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Euphydryas anicia hermosa | 2 | 1 | Catron |

| Hesperia pahaska williamsi | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Limenitis weidemeyerii angustifascia | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Pholisora albicirrus | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Poladryas arachne nympha | 1 | 1 | Catron |

| Callophrys affinis apama | 6 | 1 | Cibola |

| Callophrys fotis | 2 | 1 | Cibola |

| Icaricia icarioides nigrafem | 9 | 1 | Colfax |

| Lon hobomok wetona | 4 | 1 | Colfax |

| Oeneis ridingsii ridingsii | 2 | 1 | Colfax |

| Anthocharis cethura pima | 2 | 1 | Doña Ana |

| Apodemia duryi | 2 | 1 | Doña Ana |

| Callophrys henrici solatus | 1 | 1 | Doña Ana |

| Kricogonia lyside | 1 | 1 | Doña Ana |

| Yvretta carus | 1 | 1 | Doña Ana |

| Amblyscirtes nysa | 5 | 1 | Eddy |

| Amblyscirtes texanae | 1 | 1 | Eddy |

| Microtia elada | 1 | 1 | Eddy |

| Systasia pulverulenta | 1 | 1 | Eddy |

| Argynnis nausicaa nausicaa | 9 | 1 | Grant |

| Atrytonopsis deva | 1 | 1 | Grant |

| Burnsius oileus | 1 | 1 | Grant |

| Microtia perse | 1 | 1 | Grant |

| Telegonus cellus | 1 | 1 | Grant |

| Poladryas minuta | 1 | 1 | Harding |

| Agathymus aryxna | 2 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Apodemia cleis | 2 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Asterocampa leilia | 2 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Chlosyne theona thekla | 2 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Codatractus arizonensis | 1 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Euptoieta hegesia meridiania | 1 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Microtia dymas chara | 6 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Microtia elvira | 1 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Sisymbria sisymbrii transversa | 1 | 1 | Hidalgo |

| Anaea aidea | 1 | 1 | Lea |

| Argynnis nausicaa capitanensis | 33 | 1 | Otero |

| Anthocharis julia prestonorum | 1 | 1 | Rio Arriba |

| Boloria myrina tollandensis | 1 | 1 | Rio Arriba |

| Colias scudderii | 1 | 1 | Rio Arriba |

| Euphilotes stanfordorum | 5 | 1 | San Juan |

| Pontieuchloia beckerii | 3 | 1 | San Juan |

| Euphilotes rita coloradensis | 4 | 1 | Sandoval |

| Yvretta rhesus | 1 | 1 | Socorro |

| Colias meadii | 5 | 1 | Taos |

| Erebia magdalena | 2 | 1 | Taos |

| Euchloe ausonides coloradensis | 5 | 1 | Taos |

| Euphydryas anicia brucei | 3 | 1 | Taos |

| Lycaena cupreus snowi | 1 | 1 | Taos |

| Oeneis melissa lucilla | 6 | 1 | Taos |

| Oeneis uhleri uhleri | 1 | 1 | Taos |

| Papilio indra minori | 1 | 1 | Taos |

| Anatrytone logan lagus | 2 | 1 | Union |

| Atrytonopsis hianna turneri | 1 | 1 | Union |

| Gesta martialis | 1 | 1 | Union |

| Satyrium favonius violae | 3 | 1 | Union |

As you can see from this table, Hidalgo had the most unique species (no big surprise there), but there were 3 unique species from Bernalillo, two of which were quite remarkable – Zebra Swallowtail and Zebra Heliconian. The Zebra Heliconian has been recorded from Bernalillo County before, but the Zebra Swallowtail is very unexpected. We suspect an escapee from the BioPark, but our attempts to contact the observer have been unsuccessful so far. The nearest record of the Zebra Swallowtail to this one is more than 500 miles away to the east (Oklahoma City).

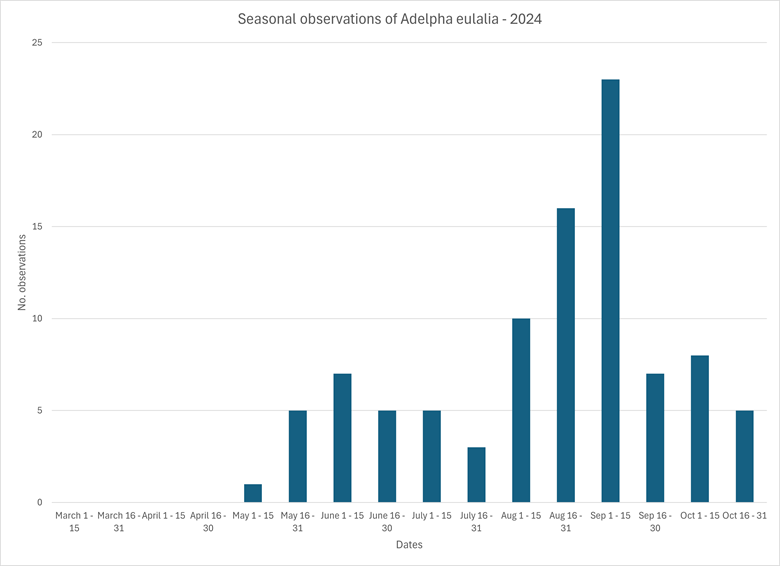

These data also lend themselves to other sorts of analyses. For example, we can look at the seasonal distribution of each species and see if any patterns appear. If we add observations from other years, we might be able to see some trends (global warming, anyone?). I compared seasonal distribution in the Arizona Sister (Adelpha eulalia) in 2024 and then in 2023 – 2024: here’s what that looks like:

2024 seasonal distribution

Two generations?

2023 – 2024 seasonal distribution

While we can’t make any earth-shaking conclusions from this (does look like two generations, though, doesn’t it?), I hope you can see the potential.

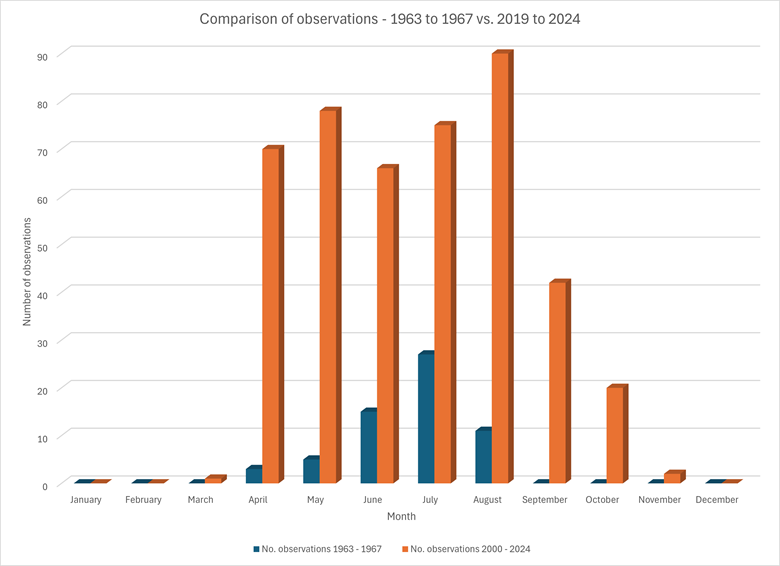

Before Steve, Simon and I went to the Lepidopterists’ Society meeting in August 2025, I had worked on similar graphs for the Two-tailed Tiger Swallowtail (Pterourus multicaudata) using a more extensive data set (see below):

Of course, there were many more observers of the Two-tailed Tiger during the period 2019 to 2024 than there were during 1963 – 1967, but preliminary statistical analyses show significant differences between these observation sets. The Two-tailed Tiger appeared earlier and lasted later in 2019-2024 than in 1963-1967. All this goes to show just how valuable your observations are. Three cheers for citizen science!

Finally, Mike and I are almost done updating the Skippers VI: Folded-wing Skippers (Hesperiinae) web page of BONM. The old page was frozen due to memory overload. Users could access it, but we could not make any corrections, changes or updates to text, photos or maps. Why that page was so overloaded is anyone’s guess, but it may have to do with the fact that ma ny Hesperiinespecies perch with such weird wing angles that multiple photographs were needed to fully illustrate the critters. We solved the problem (with PEEC’s help) by dividing folded-wing skippers into two pages where there had been one. We still need to update the hotlinks and searchable connections between the index and the place on each page for each species. We’re getting there!

We hope you have a very enjoyable Thanksgiving!

The charts are impressive and informative. Thank you, Mike. And thank you, Steve, for keeping us updated.

An interesting observation from Los Alamos – according to iNaturalist before 2025 there were only 3 previous records of American Snout. This year I saw dozens of them along Upper Water Canyon and Upper Los Alamos Canyon in October and early November. I read they are highly migratory and huge numbers are recorded in places like Texas. Two hypotheses:

1) They’re in these canyons every year but Summer’s over and not a lot of people are looking for butterflies

2) Lots of rain this summer increased the overall population causing a few to come up our way.

Anyway I got lots of pictures of snouts and it was fun to learn something new.

Michael, thanks much for your thoughts and comments. Learning something new is what it’s all about. They are inherently prone to dispersing northward every year, but there are bad years (when conditions limit their numbers and dispersal) and good years (when conditions are good, producing population explosions) in their more southerly breeding areas, including southernmost NM. They do not reproduce in the north because there are few/no hostplants. This year must have been one of those years with prime conditions for population size and dispersal. In the past, such dispersal would have been cut off by our traditional October killing frost, but this year cold weather was delayed until November, allowing them another few weeks of dispersal, so they reached farther north in larger numbers than we have usually seen.

Good points Michael Smith. Here in my yard in Tucson I have both larval hosts for snouts so essentially I have a snout lab. I think 1st instar snout larvae may require fresh leaves. They apparently cannot eat older plant growth so female snouts just hang out waiting for the rains to produce such growth. I had no snout action until mid-September when we finally got rain and both my Celtis pallida and C. reticulata put out fresh leaves. Snouts began arriving daily until I would have 20 -30/day in the yard. The larvae go thru quickly but I’m not sure how fast? Maybe in less than three weeks. Their movements north this fall were also recorded in central California. It’s interesting how these events can be regional in nature! Your first point is also quite valid. I once found a snout in August in the Saguache Valley of Colorado near Moffat, well to the north of N.M.

I reared snouts here in IL years ago. I need to find my notes, but my recollection is that they completed development in 10 days or less!