by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver

The Brushfoots (Nymphalidae). This family is our second richest in terms of number of species and perhaps the most variable in terms of sizes, colors, patterns and behaviors. Despite the obvious differences in wing morphology, almost all members share a unifying structural character: on adults, the forelegs are reduced to tiny, brush-like structures, leaving only four functional legs. The exception that proves the rule is female Libytheinae, which have functional forelegs, emphasizing their ancestral status. Many of our most familiar butterflies are members of this family. Pursuant to Pelham’s (2023) catalog, we have ~100 species in ten subfamilies distributed as shown below. Other works may arrange, lump, or divide families in other ways. Updated June 16, 2023

- Libytheinae: Snout Butterflies (1),

- Danainae: Milkweed Butterfllies (3),

- Heliconiinae:Fritillaries and Longwings (17),

- Limenitidinae: Admirals and Sisters (4),

- Apaturinae: Emperors (4),

- Biblidinae: Tropical Brushfoots (3 or 4?),

- Cyrestinae: Daggerwings (1),

- Nymphalinae: True Brushfoots (48?),

- Charaxinae: Leafwings (2), and

- Satyrinae: Satyrs (17).

Snouts (Libytheinae). Does it seem silly to erect an entire subfamily to house one (okay, two) species? I suppose the Snouts must be just that different. In fact, they seem to be a very ancient branch of the Nymphalid family: there are fossils from the Florissant Fossil Bed (~34 million years old) and each continent (except Antarctica) has at least one species (but rarely more). Females have well-developed front legs, unlike any other Nymphalid. A number of phylogenetic studies show that Libytheines are at the root of the family Nymphalidae, further supporting their ancient heritage. There is one species of snout butterfly in North America, a second in the Caribbean. Updated June 16, 2023

- American Snout (Libytheana carinenta larvata) Libytheana bachmannii

Libytheana carinenta (Cramer 1777) American Snout (updated June 22, 2023)

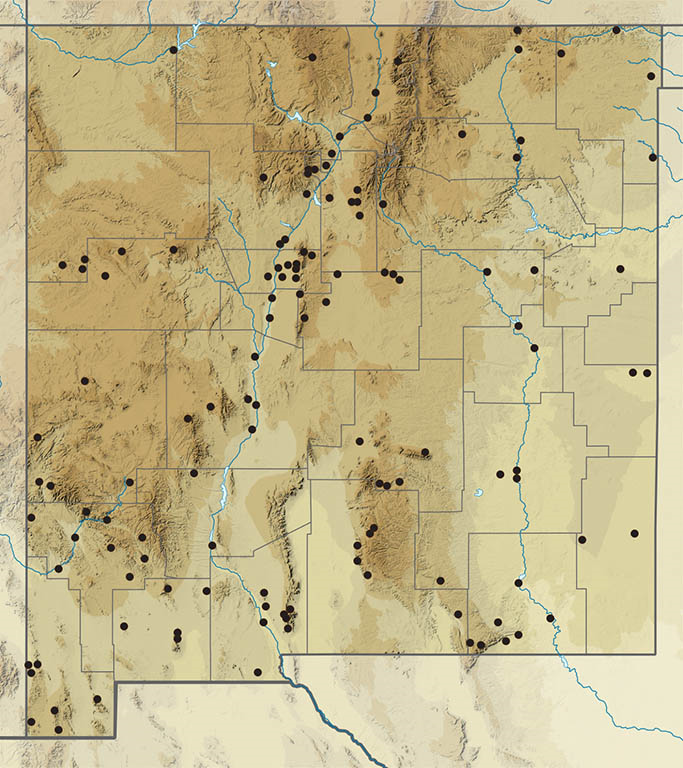

Description. This, the only member of this subfamily found regularly in the US, is identified by the elongated palpi (the “snout”) and the notch in the outer forewing margin. Libytheana carinenta has orange patches on dark wings, with white spots near the dorsal forewing apex. The underside is iridescent gray when freshly emerged, aging to mottled, camouflaged gray. The combination of wing shape and ventral colors mimics a dried leaf when perched on a twig, wings closed; the “snout” serves as a leaf “petiole.” Range and Habitat. Snouts are common in Mexico and the southern US, including southern New Mexico (counties: all but Cu). It lives in Upper Sonoran Zone riparian habitats where the larval hosts thrive. This species is strongly dispersive and expansionary, often penetrating far north during late summer and fall, but apparently with no return flight in autumn. Life History. Larvae eat foliage of hackberry trees (Ulmaceae). In our area Snouts use Celtis reticulata and Celtis pallida, scrubby trees that grow in riparian canyons and arroyos in southern and eastern New Mexico. Flight. New Mexico records fall between January 2 and December 28, indicating almost year-round presence in the south in mild winters. Farther north, snouts are winter-killed and must reinvade each year from farther south, after which it may produce up to two warm season broods. Individuals flying in early spring may have overwintered in southern NM. Peak numbers are in July to October. Adults come to riparian nectar (e.g., Baccharis). Comments. Other guides may present this butterfly as Libytheana bachmannii Kirtland, but that name no longer applies. Our Snouts belong to subspecies Libytheana carinenta larvata (Strecker). J. D. Eff reported “thousands” in Belen (Va) from 29 June to 15 July 1950.