by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver

The Brushfoots (Nymphalidae). This family is our second richest in terms of number of species and perhaps the most variable in terms of sizes, colors, patterns and behaviors. Despite the obvious differences in wing morphology, almost all members share a unifying structural character: on adults, the forelegs are reduced to tiny, brush-like structures, leaving only four functional legs. The exception that proves the rule is female Libytheinae, which have functional forelegs, emphasizing their ancestral status. Many of our most familiar butterflies are members of this family. Pursuant to Pelham’s (2023) catalog, we have ~100 species in ten subfamilies distributed as shown below. Other works may arrange, lump, or divide families in other ways. Updated June 26, 2023

Tropical Brushfoots (Nymphalidae: Biblidinae). This subfamily is tropical and subtropical in composition and contributes only four strays to our butterfly fauna. Of those, only the Common Mestra is seen here with any regularity. Membership in this group is under debate among taxonomists. There is no doubt that other butterfly species in this family have wandered to New Mexico or will do so in the future. It is a large family with many species. In fact, several other Biblidine species have been anecdotally reported from our state, but without substantiating data. The discussion below addresses those species for which a date, location and observer are confidently known. Photos are needed.

- Dingy Purplewing (Eunica monima) Florida Purplewing, Eunica tatila

- Blackened Bluewing (Myscelia cyananthe)

- Gray Cracker (Hamadryas februa)

- Glaucous Cracker (Hamadryas glauconome)

- Guatemalan Cracker (Hamadryas guatemalena)

- Common Mestra (Mestra amymone)

Eunica monima (Stoll 1782) Dingy Purplewing (updated August 13, 2023)

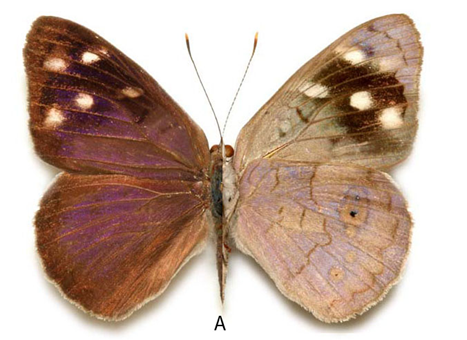

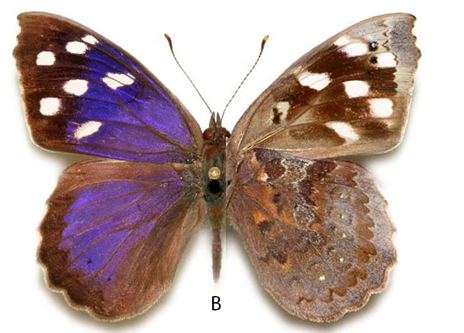

Description. Dingy Purplewing is far from dingy; males sport a bright purple sheen on the upperside. Forewing has a series of apical white spots. Females are similar but lack the purple sheen. Beneath, the ground color is a light grayish brown with a subtle arrangement of darker brown lines. The apex of the forewing repeats the white spots of the upper surface. The hindwing has a series of small postmedian spots. Range and Habitat. Dingy Purplewing is native to Central America, the Caribbean and south Florida. It occurs in our area rarely as an accidental stray. Life History. In its tropical habitat, larvae are herbivores on Zanthoxylum pentamon, a member of the citrus family (Rutaceae). Flight. Dingy Purplewings produce continuous generations in their tropical home. Individuals turn up in our area preferentially in late summer, coinciding with southerly air flow during the monsoon season. Adults are adept fliers, alighting on the undersides of leaves with their heads down, disappearing from view. Comments. Our solitary report came from Cloverdale (Hidalgo County), on 1 August 1986 (Kilian Roever). Adults will feed at flowers, tree sap, excrement and moist earth. There is a (very) slim chance that a related species could be found in the SE corner of NM: the Florida Purplewing – Eunica tatila tatila (Herrich-Schäffer [1855]) – was recorded from Ector County, TX, barely 30 miles from our SE border. Florida Purplewing is distinguished from Dingy Purplewing by a concave tip at the apex of the front wing, more extensive white spots in that area, and a mottled and darker ventral surface.

Purplewings – dorsal left, ventral right. A. Dingy Purplewing (Eunica monima) male: San Blas Mecatan, 260m, Mexico, Nayarit 1-X-1996. B. Florida Purplewing (Eunica tatila) male; Cabo Corrientes ca. 15.5 km S Mismaloya, Mexico, Jalisco 13-15-XI-1995 (Photos by Andy Warren).

Myscelia cyananthe (C. Felder & R. Felder 1867) Blackened Bluewing (updated August 16, 2023)

Description. Bluewings are unmistakable; bright blue stripes on the upperside of both wings on a dark background. Two species are known from the US, but so far only the Blackened Bluewing has found its way to NM. Blackened Bluewing is distinguished from its close relative, the Mexican Bluewing (Myscelia ethusa [Doyère 1840] – a very unlikely stray to NM), by the darker apex of the dorsal forewing and the broader blue bands on the dorsal hindwing. Otherwise, no other butterfly currently known from NM approaches this species in appearance. Range and Habitat. All the Myscelia species are tropical and subtropical. They prefer shaded tropical forests. Life History. The nearest breeding areas for the Blackened Bluewing are the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Mexico, including much of Sonora. Myscelia cyananthe flies and breeds year-round in the tropics. Flight. Occasional strays are reported from Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, usually in late summer and autumn. Comments. Our single record is from 12 May 1902, when an individual was captured in Dry Canyon near Alamogordo at the base of the Sacramento Mountains (Otero County) by Henry L. Viereck (Skinner 1902c).

Hamadryas februa (Hübner [1823]) Gray Cracker (updated August 17, 2023)

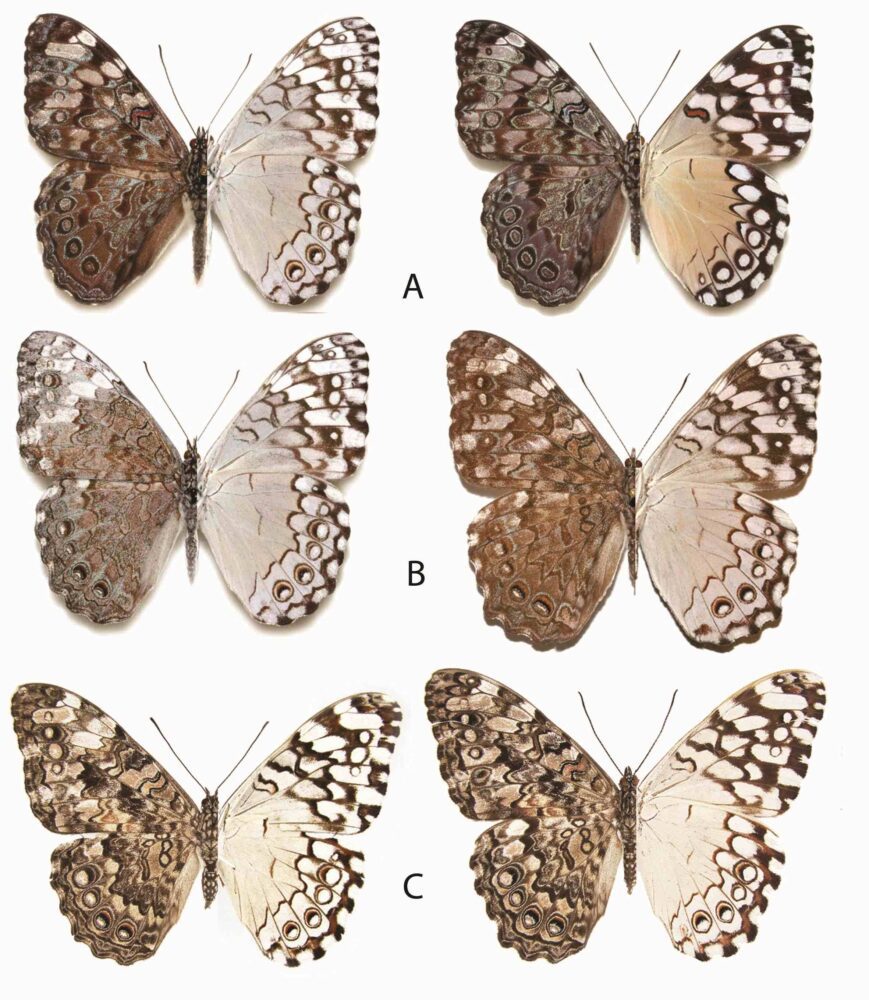

Description. Crackers are a complex group, difficult to distinguish from one another though very distinct as a group. The mottled pattern on the dorsal surface is characteristic of Crackers and will serve to separate them from all other butterflies here. Jenkins (1983) published a revision of the group which included a key to aid in identification. Seasonal and individual variation drastically increases the difficulty of recognizing species; in most cases a collected specimen would be necessary to identify which species one has. With that in mind, the Gray Cracker might be separated from the very similar Glaucous Cracker (Hamadryas glauconome grisea Jenkins, 1983) by the nature of the cross bar at the end of the DFW cell; more complex with some red and darker in februa, and lighter and simpler in glauconome. Range and Habitat. The various Crackers (Hamadryas species) are a subtropical group distributed northward from Argentina, reaching North America only infrequently and by accident. They inhabit Lower Sonoran Zone woodlands and may very well ride our warming climate farther north into New Mexico with greater frequency. Life history. Euphorbiaceae (e.g., Dalechampia species, Tragia species) are larval hosts, but there is no evidence of breeding in New Mexico. Flight. Gray Cracker is multivoltine farther south. Males perch head-down on tree trunks with wings laid flat, then dart out at passing butterflies while making a cracking sound with specialized abdominal structures. Presumably the sound warns away competing males and attracts females. Comments. Our one report is dated 19 July 1990, from Clanton Draw, Peloncillo Mountains (Hidalgo County) by Kilian Roever, suggesting occasional penetration into New Mexico during the summer monsoon.

Hamadryas glauconome (H. Bates, 1864) Glaucous Cracker (added March 17, 2025

Description. Glaucous Cracker has the typical Cracker pattern of mottled gray with a series of submarginal eyespots on the dorsal surface; a repeat of that pattern on the ventral surface near the margins while the basal region becomes more or less unicolorous. Jenkins (1983), figures 2 – 4, noted that the cross bar at the distal end of the FW cell was narrow on Glaucous, wide on Gray Cracker (H. februa) and Gray Cracker has red in that bar. The bar width may be as variable as many of the other characters in Hamadryas. There is an eye spot in cell Cu1, Cu2 of the VFW in Glaucous which is lacking in the Gray (hard to see in living individuals as they usually perch with wings opened). Glaucous males typically have a light colored DFW apex, lacking in the Gray Cracker. However, seasonal, sexual and individual variation complicates identification of Crackers; best identification would come from a collected specimen. Range and habitat. Tropical to sub-tropical, like other Hamadryas. Its usual range is from Central America to northern Mexico, but it strays north to AZ, NM, and TX. Life history. Preferred larval host is Dalechampia scandens, which is not found in the SW US. (Bailowitz and Brock 2022). Flight. The species flies all year in its native habitat. Our record is from September. Comments. An individual of Hamadryas (probably glauconome) was observed in Skeleton Canyon, T31S, R22W, Sec 23, Peloncillo Mts., 19 September 2001, by William H. Baltosser. In his extensive notes on this observation, Dr. Baltosser noted the “presence of the violet wash” on the dorsal surface, an important character per Ramirez (1987). Our subspecies would be H. glauconome grisea Jenkins, 1983. Note the comparison plate, below, of Hamadryas species that occur, or could occur, in NM. In subspecies grisea, the degree of paleness in the DFW of males varies and may be darker in some individuals.

Hamadryas guatemalena (H. Bates, 1864) Guatemalan Cracker (added March 17, 2025)

Description. Crackers (Hamadryas) are very distinctive as a group, but identifying species within that group can be challenging – see Jenkins 1983. Hamadryas guatemalena is about the size of a Great-spangled Fritillary (Argynnis cybele) – about 3.5 inches. Guatemalan Cracker shows the typical dorsal and ventral mottled patterns of other Hamaydryas, but is distinguished from other Crackers found (or possibly found) in NM by its bluish overlay on the dorsal surface, the shape and color (some red, like februa) of the distal crossbar in the cell of the FW, and the eye spots on the DHW which tend to be more “eye-like” than the eye spots in Glaucous (which tend to have a crescent pupil). Both the FW and HW have a series of submarginal eyespots; those on the HW are “donut shaped” (Jenkins 1983). The male DFW apex is usually darker, as opposed to the lighter color on Glaucous. Ventrally, males have extensive areas of light grey, while females have that region ochraceous. The pattern of mottling and spots is repeated near the margins, but much lighter in color. Range and habitat. Tropical to sub-tropical, like other Hamadryas. Its usual range is from Central America to northern Mexico, but it strays north to AZ, NM, and TX. Life history. Larvae eat Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae), a genus of plants which apparently doesn’t occur in the US. Since a number of fresh specimens have been observed or captured in SE AZ and SW NM, perhaps another Euphorb is used. Some species do use Tragia, which is found in NM. (Bailowitz and Brock 2022). Flight. The species flies all year in its native habitat. The single AZ record is from October. Comments. There is a record for Guatemalan Cracker from Portal in SE AZ, close to the NM border. Our subspecies would be H. guatemalena marmarice (Fruhstorfer, 1916). Note the comparison plate, below, of Hamadryas species that occur, or could occur, in NM.

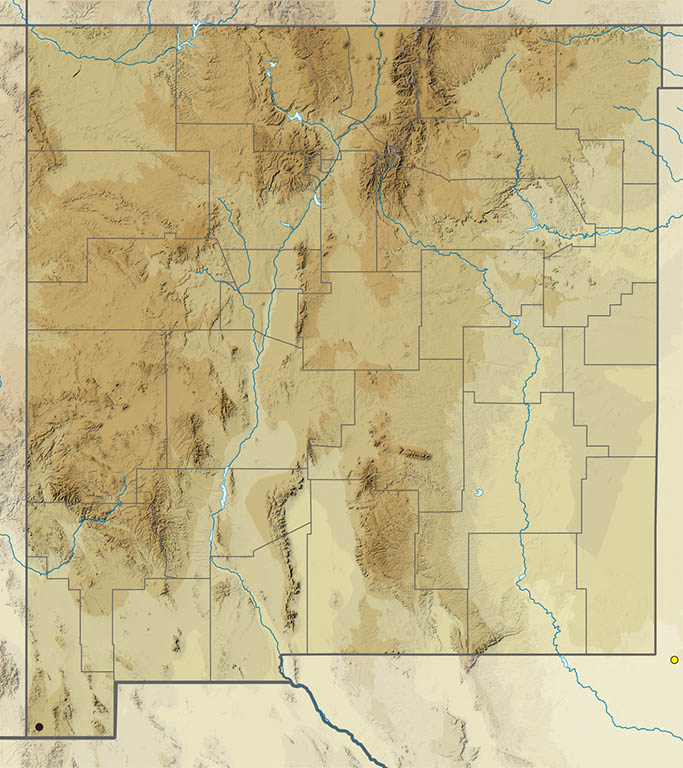

Mestra amymone (Ménétriés 1857) Common Mestra (updated August 17, 2023)

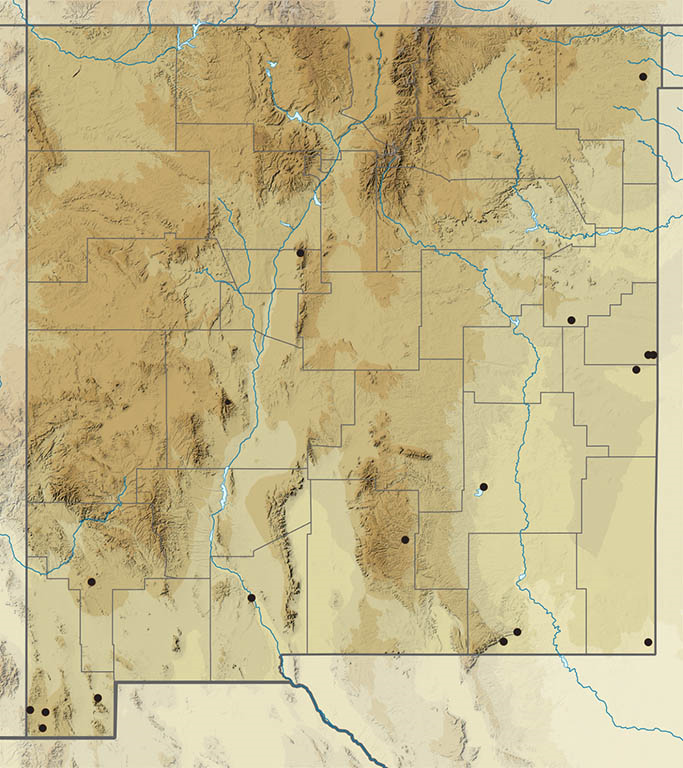

Description. Mestra is of modest size, rather pale (it reminds one of a Pierid rather than a Nymphalid) and rounded. The ventrum is apricot in color with bands of white spots. The upperside is white with gray patches. Black vein-ends give the wing margin a scalloped appearance. Range and Habitat. Mestra amymone lives from Central America northward along both Mexican coasts as far as south Texas. Adults stray northward in summer, singly or in groups, sometimes well into the Great Plains. It wanders somewhat regularly to southeast New Mexico (counties: Be,Ch,Cu,DA,Ed,Gr,Hi,Le,Ot,Qu,Ro,So,Un). Life History. Larvae eat plants in Euphorbiaceae family. Dalechampia scandens, Tragia volubilis and Tragia neptifolia are used elsewhere; Tragia ramosa is the likely host in our state. There is no evidence of reproduction in New Mexico, but a late season generation is quite conceivable. Flight. Our records of Mestra fall between July 23 and November 5, during and on the heels of summer thunderstorm season. In New Mexico, look for it in moist, shady oases where it flies slowly and delicately near the ground and siphons nectar from flowers. At times, the perching and patrolling behavior of males in moist openings suggests a search for mates. Comments. The first two New Mexico specimens of Mestra amymone are in the Carnegie Museum collection, after being captured in the Magdalena Mountains (So) in August 1894 by H. Kahl, a member of Francis H. Snow’s final New Mexico collecting expedition. As with many subtropical vagrants, years may elapse during which none are seen, but when conditions are favorable in its breeding range, it may enter our state in surprising numbers.