by Steven J. Cary and MIchael E. Toliver

The Brushfoots (Nymphalidae). This family is our second richest in terms of number of species and perhaps the most variable in terms of sizes, colors, patterns and behaviors. Despite the obvious differences in wing morphology, almost all members share a unifying structural character: on adults, the forelegs are reduced to tiny, brush-like structures, leaving only four functional legs. The exception that proves the rule is female Libytheinae, which have functional forelegs, emphasizing their ancestral status. Many of our most familiar butterflies are members of this family. Pursuant to Pelham’s (2023) catalog, we have ~100 species in ten subfamilies distributed as shown below. Other works may arrange, lump, or divide families in other ways. Updated June 26, 2023

Fritillaries and Longwings (Nymphalidae: Heliconiinae). This group of 18 butterflies includes some distinctively large, colorful fritillaries of our montane regions. They range in size from wingspans of 1.5 inches for the lesser fritillaries up to 3.5 inches for the greater fritillaries. Their larvae often favor violets (Violaceae). This subfamily also includes equally striking tropical or subtropical longwing species which are usually seen in New Mexico only as rare or infrequent strays. Their bright colors and wingspans up to 3.5 inches make them memorable sights. Larvae of several species eat passion vine (Passifloraceae). Our photographic coverage of the longwings is mediocre at best. Better images are hereby invited for our review and inclusion, with credit, of course.

- Julia (Dryas iulia)

- Banded Orange Heliconian (Dryadula phaetusa)

- Isabella Heliconian (Eueides isabella)

- Zebra Heliconian (Heliconius charithonia)

- Gulf Fritillary (Dione incarnata)

- Mexican Silverspot (Dione moneta)

- Variegated Fritillary (Euptoieta claudia)

- Mexican Fritillary (Euptoieta hegesia)

- Freija Fritillary (Boloria freija)

- Arctic Fritillary (Boloria chariclea)

- Silver-bordered Fritillary (Boloria myrina)

- Nokomis Fritillary (Argynnis nokomis)

- Great Spangled Fritillary (Argynnis cybele)

- Aphrodite Fritillary (Argynnis aphrodite)

- Northwestern Fritillary (Argynnis hesperis)

- Southwestern Fritillary (Argynnis nausicaa)

- Edwards’ Fritillary (Argynnis edwardsii)

- Bischoff’s Fritillary (Argynnis bischoffii)

- Regal Fritillary (Argynnis idalia)

- Callippe Fritillary (Argynnis callippe)

Dryas iulia (Fabricius 1775) Julia Heliconian (updated June 23, 2023)

Description. Of all our Longwings, brilliant orange Julia has the longest, narrowest wings. Males are brilliant orange above; females have a black line on the forewing to blunt the gleam. Ventral surfaces are tan, with red at the base. Range and habitat. This butterfly is neotropical, straying north to the US border. It has become fairly routine in Texas and Florida, where it may have escaped butterfly house captivity and become naturalized. It remains a very rare stray elsewhere. Life history. Larvae eat passion vines (Passifloraceae) in Mexico. Flight. Flies year around in the tropics. Strays to New Mexico would most likely be encountered in summer to late fall. Comments. Julia was seen at Ramon (county: Li) in May 2001 by the falcon-eyed Christopher Rustay. This record was replicated two decades later when one was spotted in Albuquerque’s Northeast Heights on Sept. 14, 2021, and reported to iNaturalist. Accidental escapes of this species may occur from the Albuquerque BioPark (D. Ferguson, pers. com. 2009), and this report may represent one. Wild strays to New Mexico are likely to be subspecies Dryas iulia moderata (N. Riley 1926). Plant nurseries sell a fair amount of passion vine in southern New Mexico, and this butterfly could temporarily survive or reproduce there to support rare accidental releases or rare wild strays of this species.

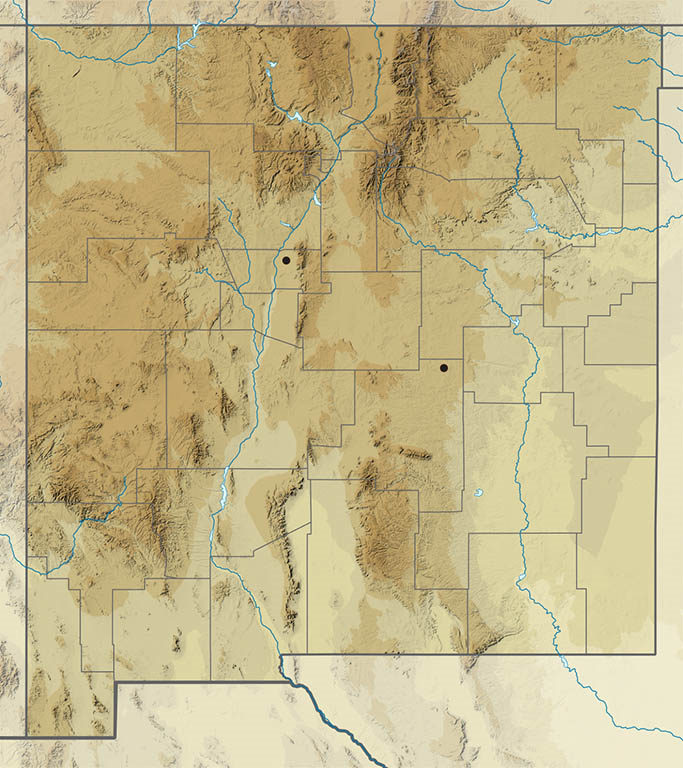

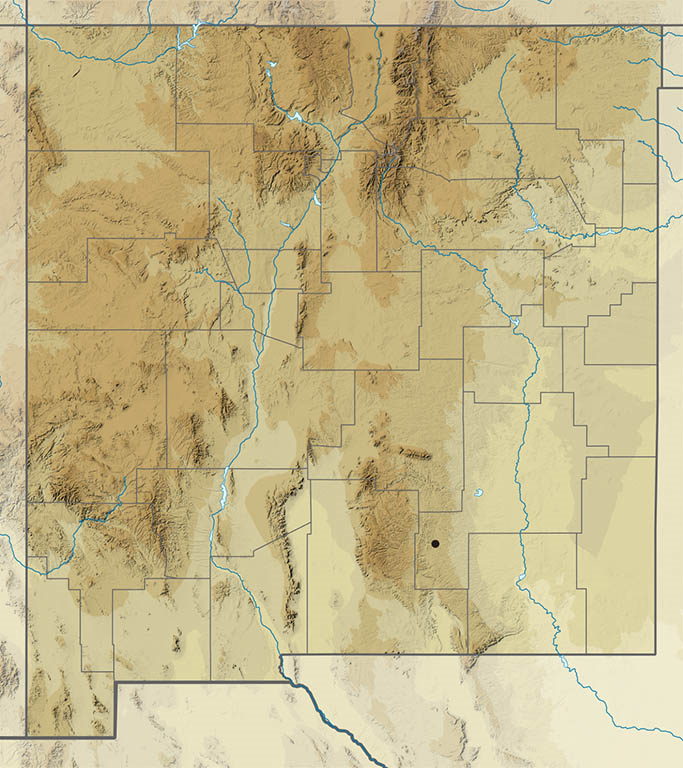

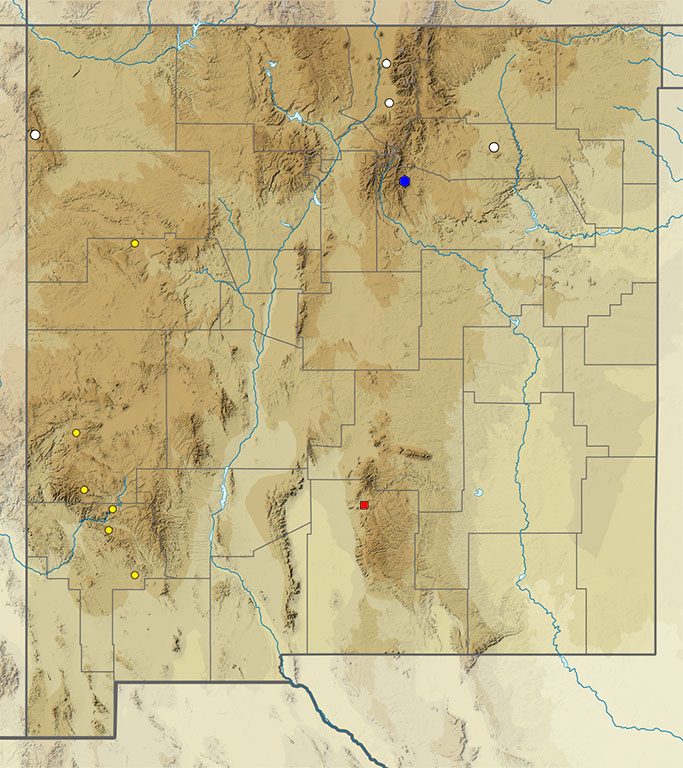

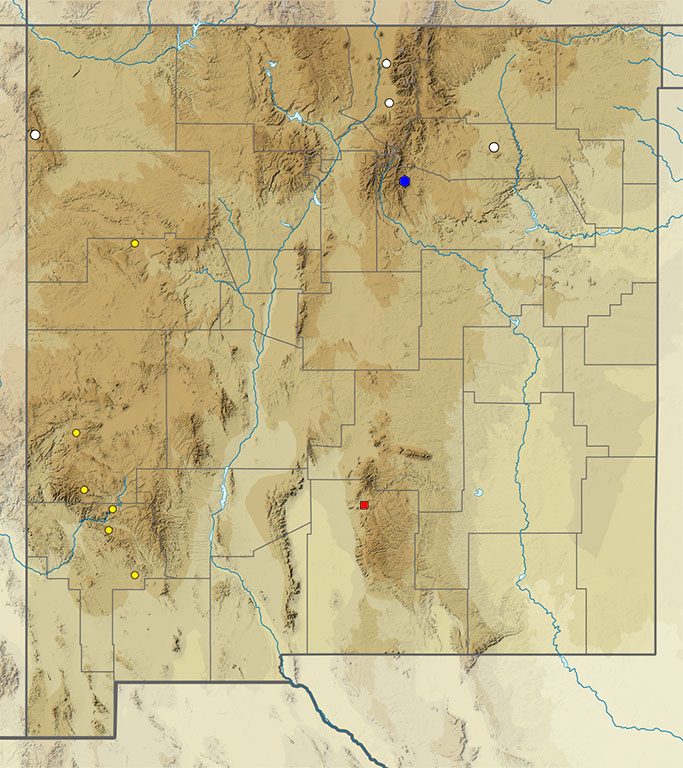

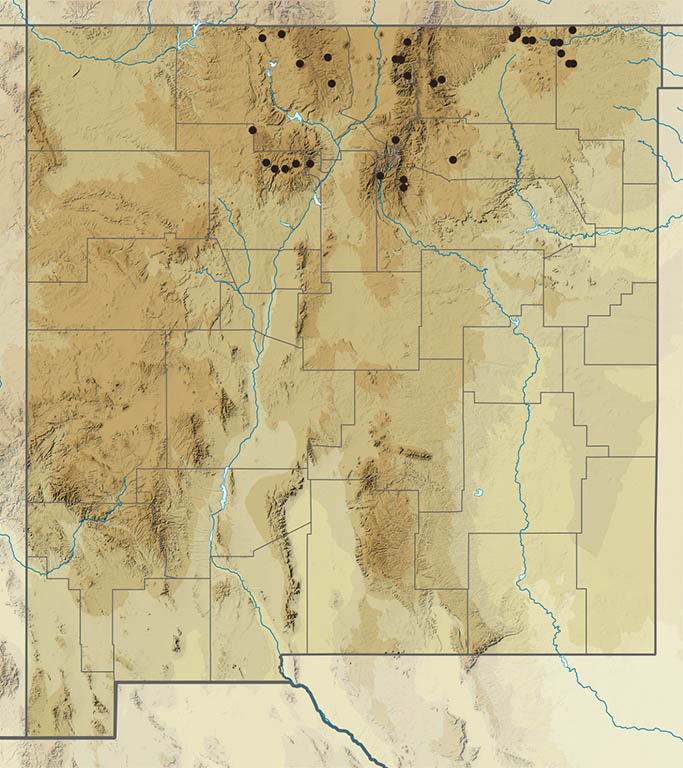

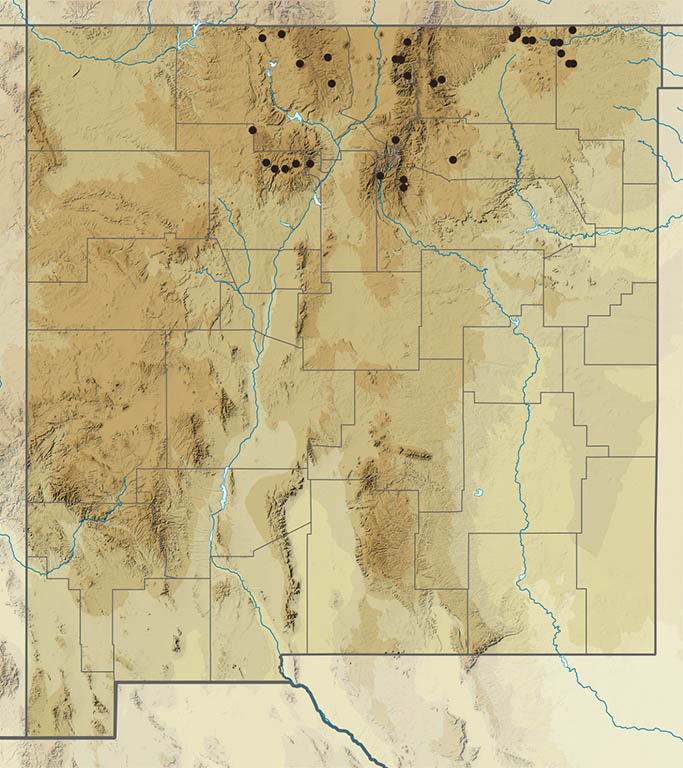

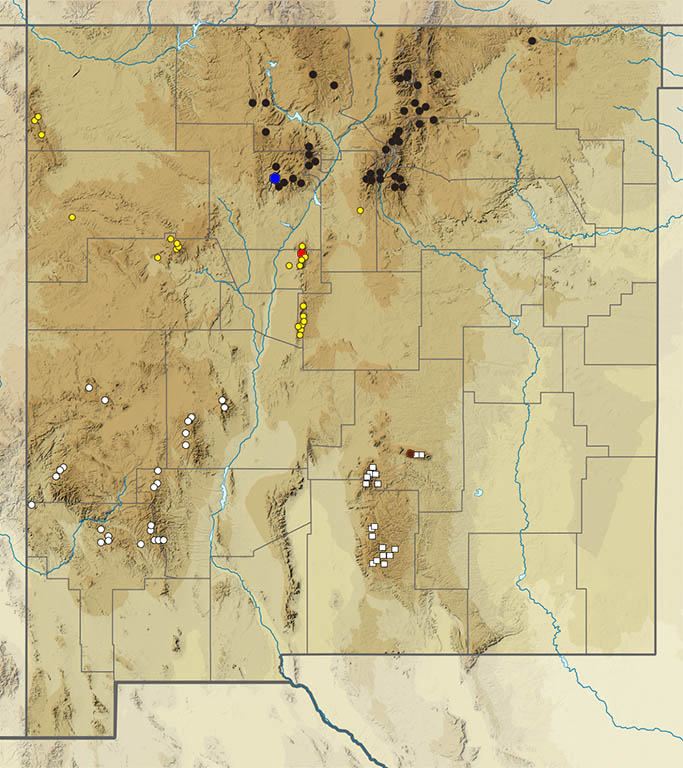

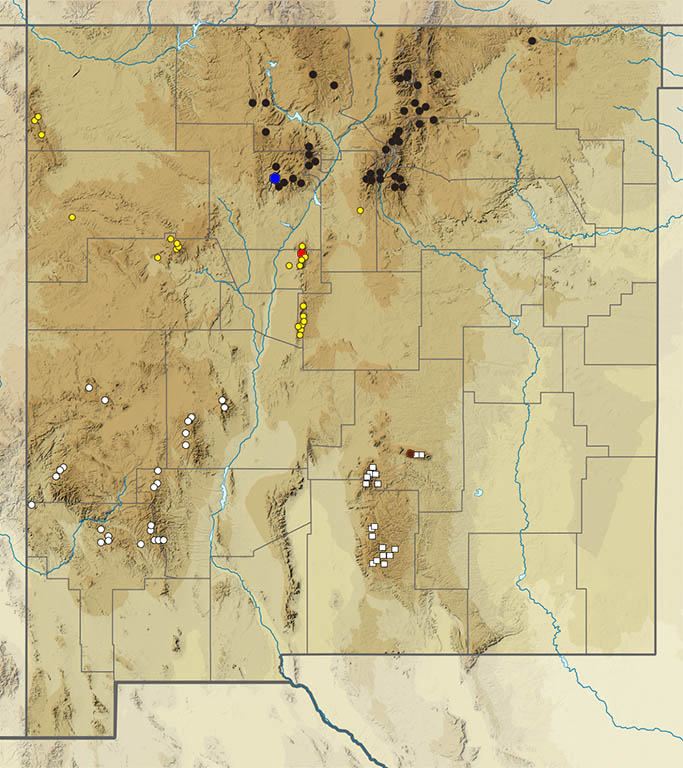

Occurrences of Julia Heliconian (Dryas iulia) in New Mexico.

Dryadula phaetusa (Linnaeus 1758) Banded Orange Heliconian (updated June 24, 2023)

Description. An unmistakable butterfly, aptly named “Banded Orange.” The upper surface of both wings is a burnt orange, with two transverse dark bands on the front wings and a single transverse band on the hind wing. Margins are edged in black, with the hindwing margin punctuated with orange dots. The ventral surface repeats the pattern of the dorsal surface in more subdued tones. Range and habitat. Dryadula phaetusa is seen in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of south Texas and a rare stray once made it all the way to Kansas, but its native range is well south of there. It is typically found in lowland tropical fields. Life history. Larvae eat Passifloraceae, but it is unlikely that any breeding by lost vagrants takes place in New Mexico. Flight. In the US, one is most likely to see this in the late summer and fall. Oddly, our record is from April. The species flies year-round in its normal habitat. Comments. This tropical creature has only once graced our state. Dan Leifheit visited Carlsbad Caverns National Park (Eddy County) on April 18, 2017. Next to the shade structure near the natural entrance used by the bats, he found an odd butterfly nectaring at Apache Plume. He submitted two photos of this butterfly to the BAMONA website. His photos were taken from a distance but that was good enough. It was unmistakably the Banded Orange Heliconian (https://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/sighting_details/1114865 ). The BAMONA reviewer for New Mexico noted as follows: “WOW! this is the first time that species has been seen in New Mexico.”

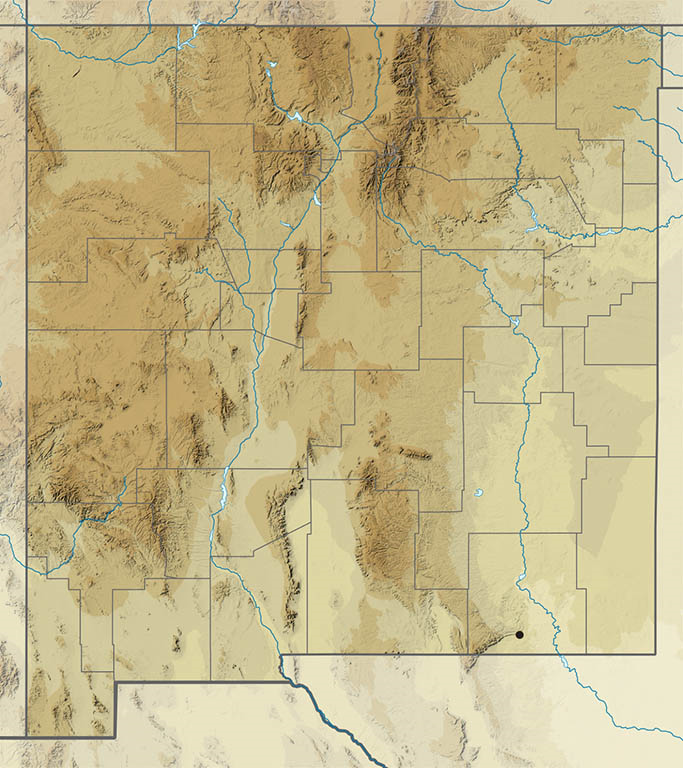

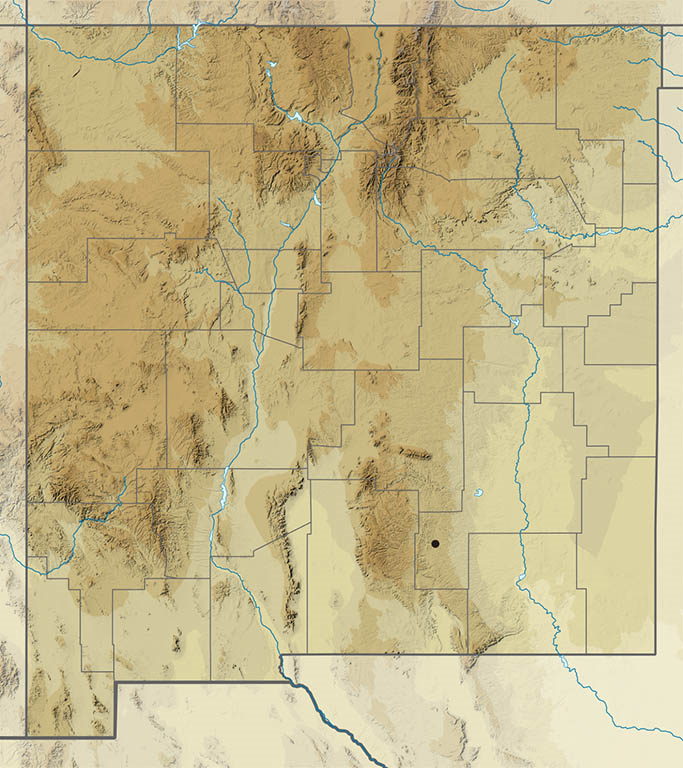

Occurrence of Banded Orange Heliconian (Dryadula phaetusa) in New Mexico.

Eueides isabella (Stoll 1781) Isabella’s Heliconian (updated December 23, 2023)

Description. In addition to the elongated forewing, Isabella is orange with black stripes and yellow at the forewing apex, making it a member of the “tiger striped butterflies” which also includes other genera of Danaines and some Ithomiines as well. Range and habitat. Neotropical in its origins, Isabella occurs in the US chiefly as a rare stray into Arizona, Kansas and New Mexico. Life History. Temporary breeding colonies may establish briefly in south Texas, using Passifloraceae as hosts. Flight. As with most subtropical strays, this species would be least unlikely during and after a productive monsoon season. Comments. Our one, undated specimen is from the Rio Peñasco on the east slope of the Sacramento Mountains near Dunken (Chaves County), in the collection of Ed Peyton.

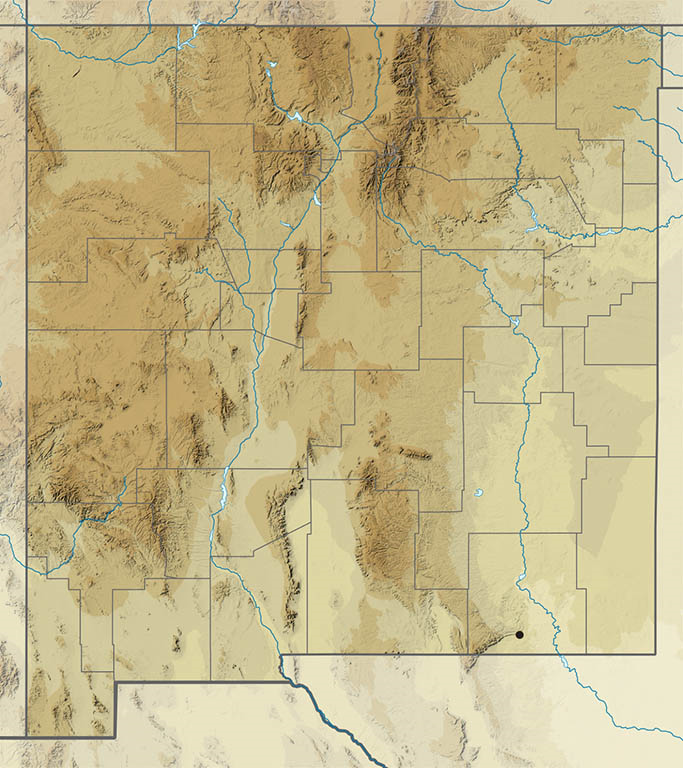

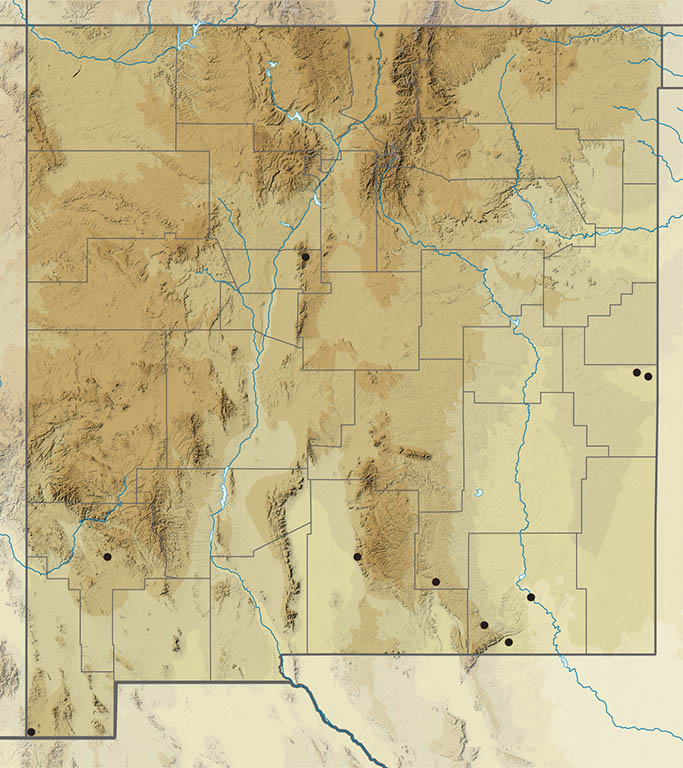

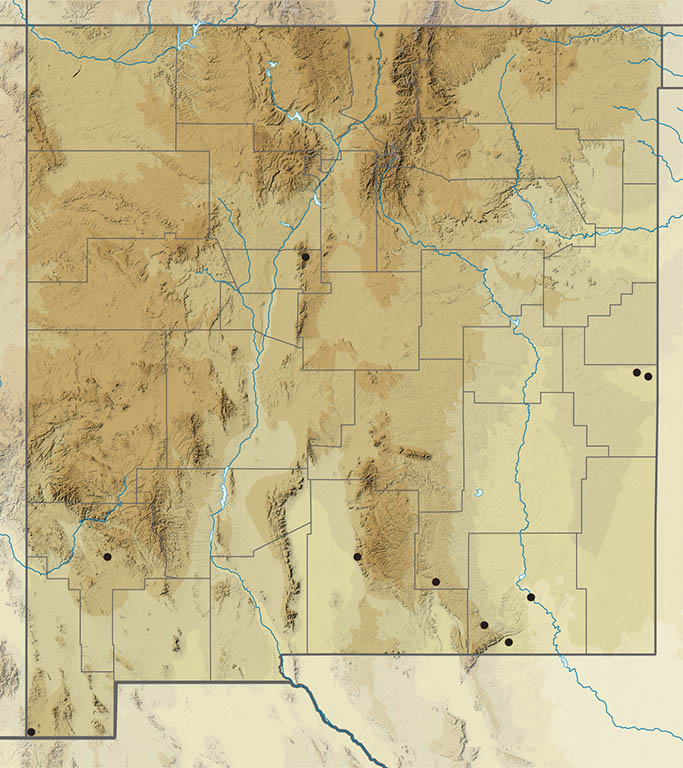

Occurrence of Isabella’s Heliconian (Eueides isabella) in New Mexico.

Heliconius charithonia (Linnaeus 1767) Zebra Heliconian (updated June 26, 2023)

Description. Distinctive Zebra is black with narrow yellow stripes running from wing bases toward the margins. Elongated forewings and the color pattern make it unmistakable in New Mexico. The posterior hindwing stripe is a collection of small yellow spots. Range and Habitat. Zebra is common in Central and South America; it breeds as far north as coastal Mexico and south Florida. Though they do not appear to be sturdy flyers, adults occasionally penetrate into the central US. Their infrequent visits to New Mexico (counties: Be,Ch,Ed,Gr,Hi,Ot,Ro) were recorded at low elevations in the south or along major watercourses. Life History. Passifloraceae (passion vines) are the only larval hosts. Flight. New Mexico records are concentrated in the period between July 19 and October 13, during and after the monsoon, but a spring brood is evident in southeast Arizona (Bailowitz and Brock 2022). Adults nectar and patrol canyons and other low spots. Comments. Dr. Dale Zimmerman reported our first Heliconius charithonia, from Silver City (Gr), on 23 August 1973. Our Zebras belong to the Mexican subspecies Heliconius charithonia vazquezae W. Comstock & F. Brown 1950.

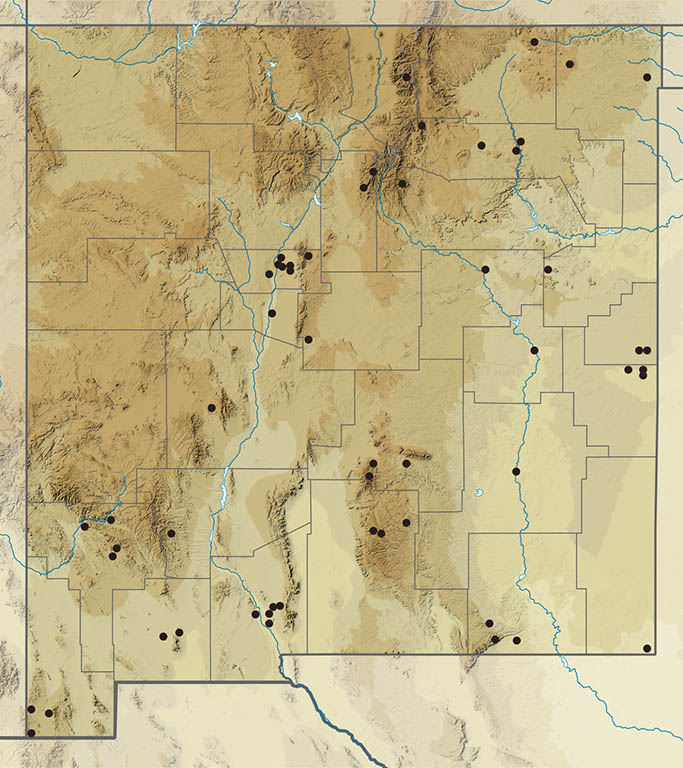

Occurrences of Zebra (Heliconius charithonia) in New Mexico.

Dione incarnata (N. Riley 1926) Gulf Coast Fritillary (updated June 27, 2023)

Description. Gulf Coast Fritillary’s elongated forewings are day-glo orange above with black maculations. The hindwing below is gold-brown with large silver spots. The orange ventral forewing has black-ringed silvery spots. Range and Habitat. This subtropical flyer breeds from Florida to coastal Mexico. An able wanderer, it strays nearly to Canada and is a regular tourist in southern New Mexico (counties: Be,Ch,Co,Cu,DB,DA,Ed,Gr,Gu,Ha,Hi,Le,Li,Lu,Mo,Ot,Qu,Ro,SM,SF,Si,So,Ta,To,Un,Va), usually below 6000′. One found its way to the top of Santa Fe Baldy, 12,600′ elevation (SF), on June 18, 2010 (Bob Jilek). Life History. Larval hosts are passionflowers (Passifloraceae). Larvae devour Passiflora in Alamogordo (Ot) and may complete a generation or two each summer, but Gulf Coast Fritillaries cannot survive our harsh winters. Flight. Gulf Coast Fritillaries visit most frequently in summer, often frequenting riparian situations. Our records fall between March 31 and December 4, peaking in July. They are never common and are not seen every year. The species seems to like hilltops. Comments. We used to call this butterfly Gulf Fritillary (Dione vanillae Linnaeus 1758), but recent DNA studies (Zhang et al. 2020; Núñez et al. 2022) indicate that ‘vanillae’ is Caribbean. Its North American cousin, Dione incarnata, is distinct; we call it Gulf Coast Fritillary. We have the nominate (western) subspecies, while Dione incarnata nigrior (Michener 1942) is the eastern subspecies.

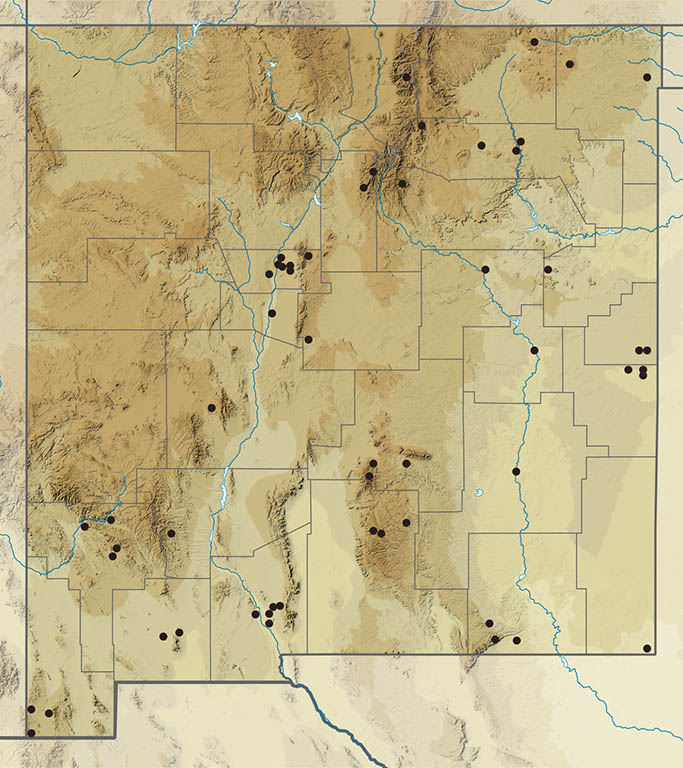

Occurrences of Gulf Coast Fritillary (Dione incarnata) in New Mexico.

Comparison of Gulf Coast Fritillary (A. Dione incarnata) and Mexican Silverspot (B. Dione moneta). Left side, dorsal; right side, ventral. Photos courtesy of Andy Warren.

Dione moneta Hübner [1825] Mexican Silverspot (updated June 28, 2023)

Description. Mexican Silverspots look like Gulf Coast Fritillaries and distinguishing them can be challenging. This species has brown wing bases dorsally, and the forewing cell lacks the spots with white centers found in the Gulf Coast Frit. Veins on fore- and hindwings are outlined in black, unlike the Gulf Coast. Ventrally, Mexican Silverspot has four silver spots at the apex of the forewing underneath as opposed to the three on Gulf Coast Frit. The forewing cell lacks the Gulf’s white-centered spots; instead, the cell is marked by black smudges. It has been said that the Mexican Silverspot resembles a Gulf Coast Fritillary on steroids. Range and habitat. Dione moneta is more tropical, less subtropical than Dione incarnata. It therefore is a much rarer visitor to the southwest US. There are only two New Mexico records (counties: Ot,Ro) from April and May. Bailowitz and Brock (2022 reported only one record from southeast Arizona and only two from all of AZ. Like the Gulf Coast Fritillary, Mexican Silverspot seems to like hilltops. Life history. Many species of Passifloraceae are larval hosts in its tropical home. Flight. The record from Sunspot (Ot) is dated 28 April 1981 (J. McCaffrey). Interestingly, records from AZ and NM are all from April and May, although one might anticipate late summer and fall would be more probable for a tropical stray like the Mexican Silverspot. Comments. Christopher Rustay also reported it from the Melrose migrant trap (Ro).

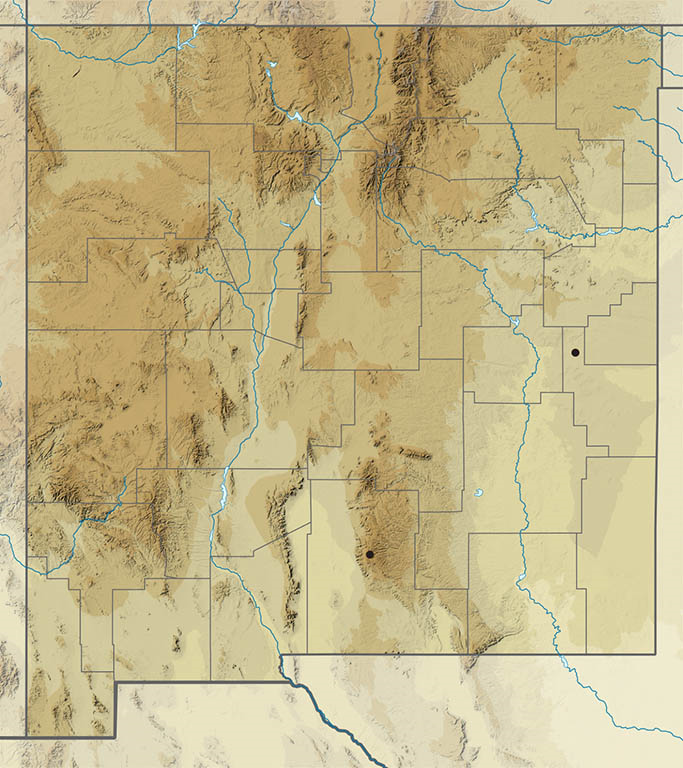

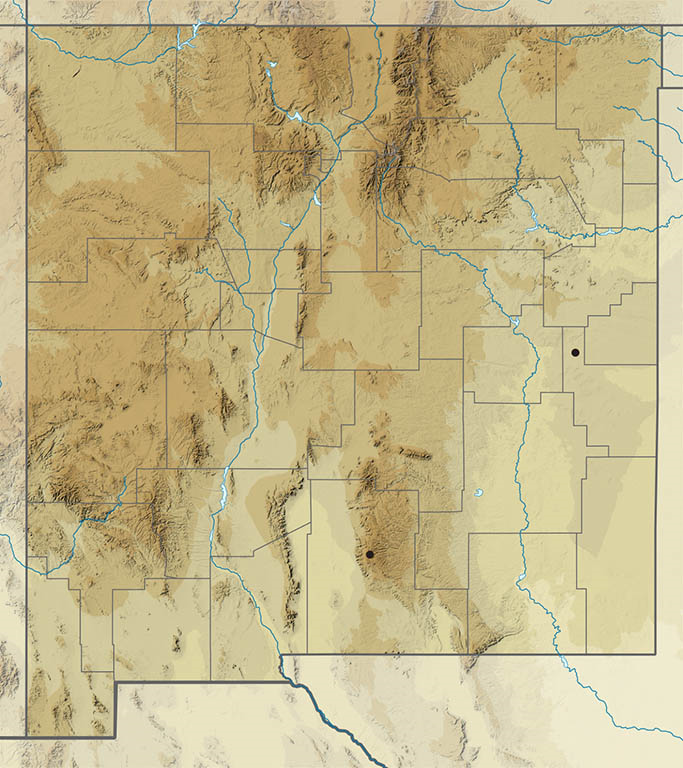

Occurrences of Mexican Silverspot (Dione moneta) in New Mexico,

Euptoieta claudia (Cramer 1775) Variegated Fritillary (updated June 28, 2023)

Description. The Variegated Frit is dull orange above with abundant and regular black markings. Below, it is mottled brown and orange, grizzled with white. Range and Habitat. This butterfly breeds in South America, Central America and in southern North America. It strays broadly across much of the US in good years. In our state it is ubiquitous (all counties) and one of our most familiar butterflies. It is more common at lower elevations, where it may reproduce year-round. Life History. Variegated Fritillaries thrive because they use widespread hosts. Native flaxes (Linaceae), some of which are common in grassland habitats or common roadside wildflowers, seem to be the primary hosts in New Mexico. James A. Scott found a larva on Linum australe near Arroyo del Agua (RA). Ellery Worthen reared a larva on Linum sp. (probably rigidum) in Albuquerque (Be). James Lofton photographed oviposition on Linum lewisii near Portales (Ro). Larvae eat pansies (Violaceae) in Santa Fe (SF). Flight. Euptoieta claudia has several broods per year, as weather permits. Our records span January 22 to December 23, peaking in mid-summer. Relatively subdued colors and low, cautious flight distinguish it from the true fritillaries. Hira Walker reported the following courtship activity on July 20, 2021: “The female stood on the ground while a male vibrated its wings, hopped a circle around her, hopped over her, and then repeated this.” Comments. Over time, Euptoieta claudia becomes easy to recognize in the field because it is seen so often. Unfortunately, many observers become so accustomed to seeing the widespread Variegated Fritillaries that they expect to see it, and they may overlook similar species that may be quite uncommon, like the next one.

Euptoieta hegesia (Cramer 1779) Mexican Fritillary (updated June 28, 2023)

Description. Mexican Fritillary has a hindwing upperside that is unmarked orange in median and postmedian areas. With fewer dark marks, this species has a much brighter look than its close relative, Variegated Fritillary. Range and Habitat. This tropical butterfly breeds north to coastal Mexico and strays to the southwest US, rarely to New Mexico. There are very few authentic New Mexico reports along our Mexico border (counties: DA,Hi,Lu?), but this species can be easy to overlook and it could be more frequently here than our sparse records suggest. Life History. Hosts are Passifloraceae, Convolvulaceae, and Turneraceae. Passiflora sp. is a reported host in Arizona. Passiflora (passionflower) hosts Gulf Fritillary in Las Cruces neighborhoods and those might be good places to look for Mexican Fritillary as well. Flight. Our scant reports span late August to December 10, consistent with monsoon-related dispersal and possible post-monsoon reproduction. Adults fly near the ground in open fields and pastures, often stopping to nectar. Comments. Our subspecies is Euptoieta hegesia meridiania Stichel, 1938.

Occurrences of Mexican Fritillary (Euptoieta hegesia) in New Mexico.

Boloria freija (Thunberg 1791) Freija Fritillary (updated June 29, 2023)

Description. Lesser fritillaries in the genus Boloria are smaller than all the greater fritillaries (Argynnis spp.), but they, too, are bright orange with fine black maculation. Uniquely, Freija has a diagnostic white triangular spot in the middle of the hindwing below, pointing toward the margin. This spot is not part of a band of similar spots. Range and Habitat. Holarctic, Freija lives from Alaska east across nearly all of Canada to Newfoundland. Pleistocene relict colonies remain in Hudsonian Zone marshes in the central Rockies, the southernmost of which is in northern New Mexico near Hopewell Lake (RA), at 10,000’. BAMONA shows an archival report in Taos County, but without any documentation. Life History. The most likely larval host for this butterfly in our area is Vaccinium caespitosum (Ericaceae). Larvae overwinter. Flight. Univoltine, adults are on the wing in mid-summer. Our only documented report (from James A. Scott) is from 21 June 1978; it has not been replicated despite multiple attempts. Adults fly near their marshy homes, basking and nectaring. Comments. Subspecies Boloria freija browni (Higgins 1953) inhabits the southern Rockies. Difficult access to New Mexico high country limits our knowledge of relict arctic species such as this one. The genus Clossiana Reuss is used for this species by taxonomists who believe that our New World taxa are distinct from the Old World taxa at the genus level.

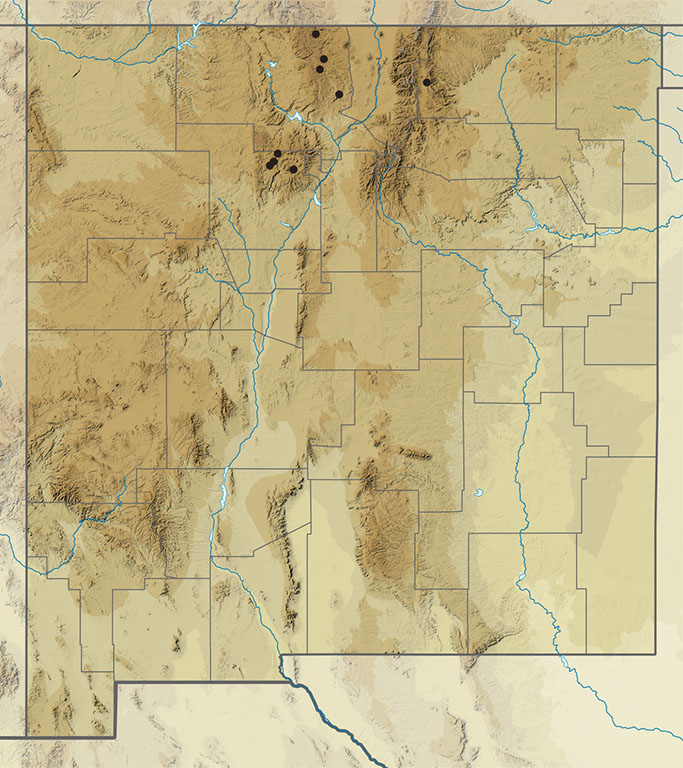

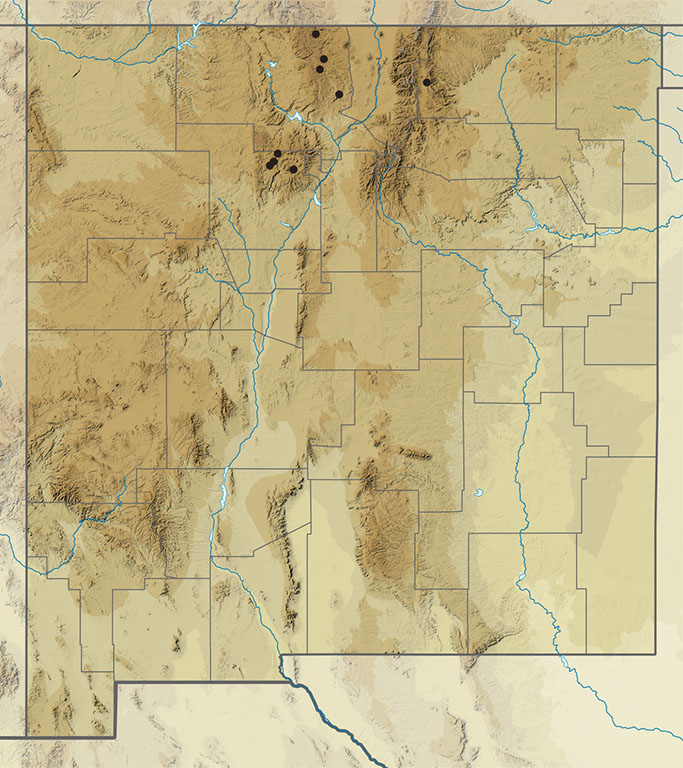

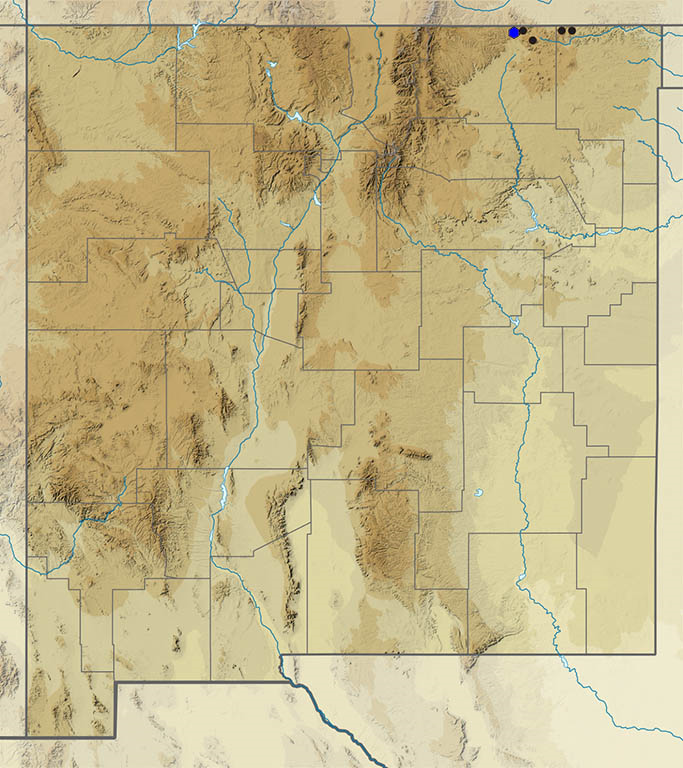

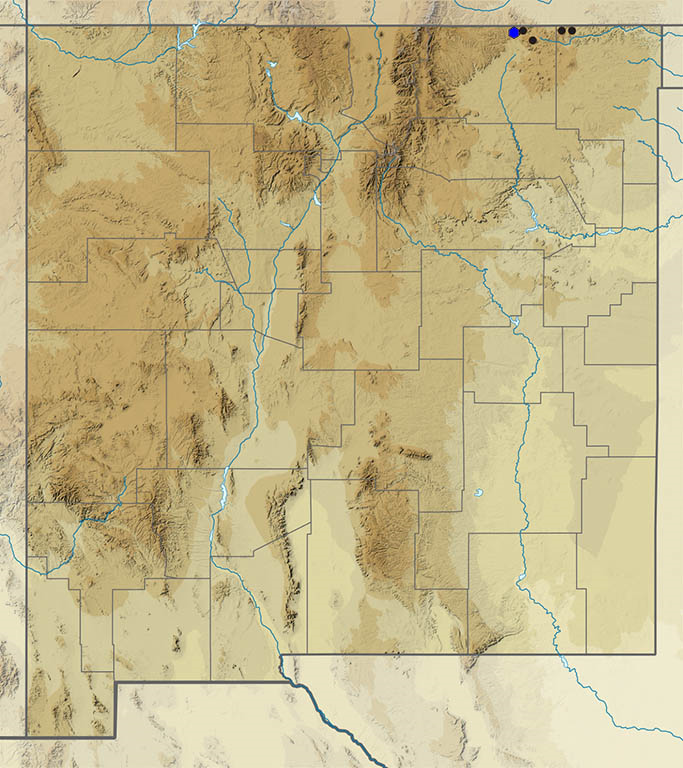

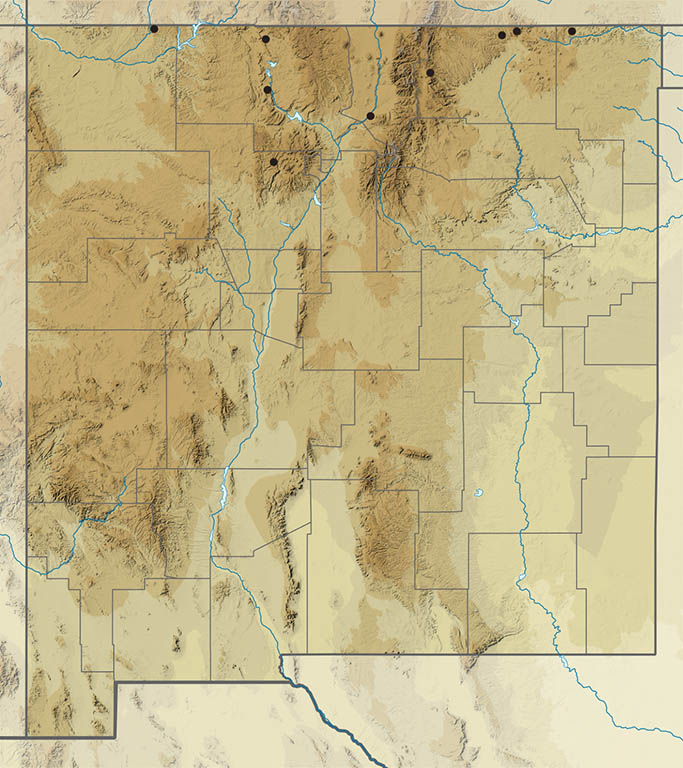

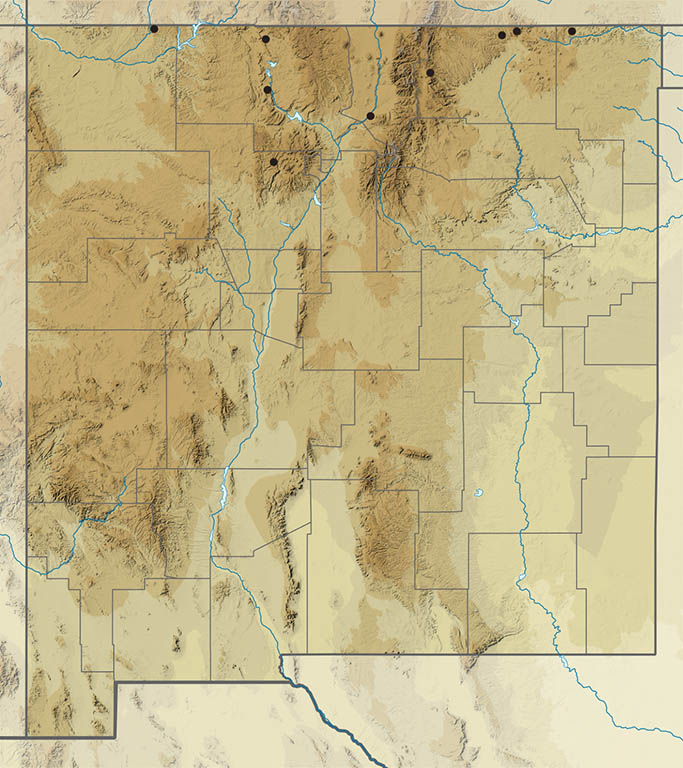

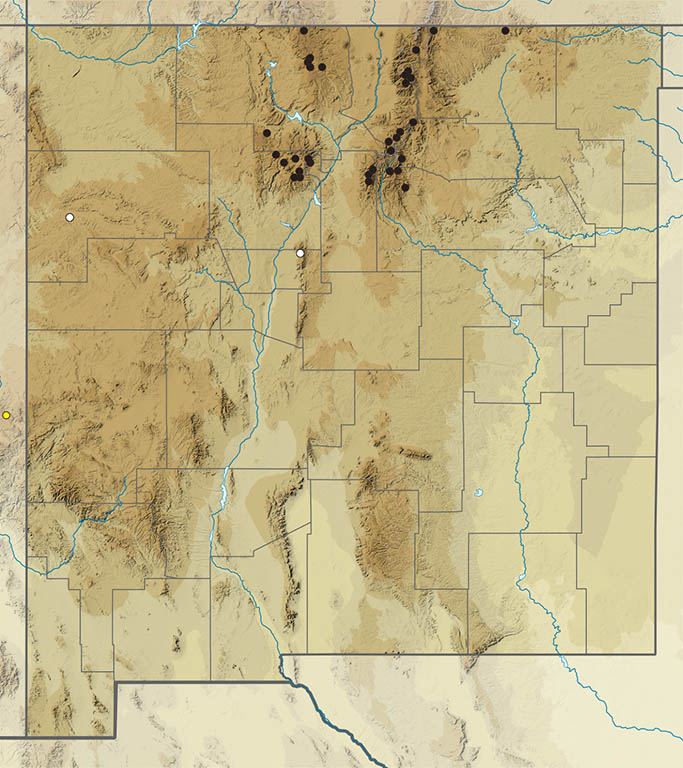

Occurrences of Freija Fritillary (Boloria freija) in New Mexico. The open circle represents an undocumented report.

Boloria chariclea (Schneider 1794) Arctic Fritillary (updated July 2, 2023)

Description. The Arctic Fritillary can be differentiated from its congeners by the maroonish ventral hindwing with a band of angular white or rusty-white spots in the median area. Range and Habitat. Boloria chariclea is the most widespread member of this genus in the Holarctic region and in North America. It occupies nearly all of Canada, Greenland and Baffin Islands. Arctic Fritillaries reach down the Cordilleran spine as far as northern New Mexico, where it is our most common lesser fritillary (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF,Ta). It inhabits Canadian and Hudsonian Zone meadows between 8500 and 12,500′ elevation. Life History. A variety of larval hostplants are reported, including members of the Salicaceae, Ericaceae, Rosaceae, Polygonaceae and Violaceae. Within the Rocky Mountain region, Scott (1992) reported oviposition on Vaccinium scoparium, V. myrtillus, and V. caespitosum (Ericaceae). He also reported use of Polygonum bistortoides, P. viviparum (Polygonaceae), and Salix nivalis (Salicaceae). Flight. The Arctic Fritillary is univoltine, or possibly biennial, with adults in flight during the brief high-altitude warm season. June 5 and September 1 encompass the flight period here, with greatest numbers observed in July. Adults are common tourists in flowery meadows where they fly near the ground, bask, perch and nectar. Comments. The central Rocky Mountains race, which includes New Mexico populations, is subspecies Boloria chariclea helena (W. H. Edwards 1871). T. D. A. Cockerell made New Mexico’s first report of this butterfly, finding it at 11,500′ near Spring Mountain (SM), on 1-4 August 1900. In recent decades this insect has gone under other names including Boloria montinus, Boloria titania and Boloria helena.

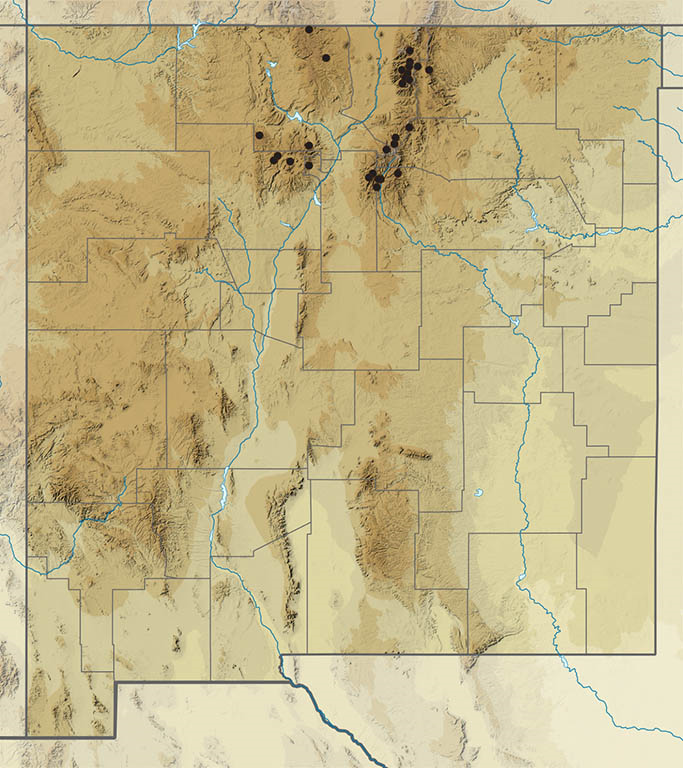

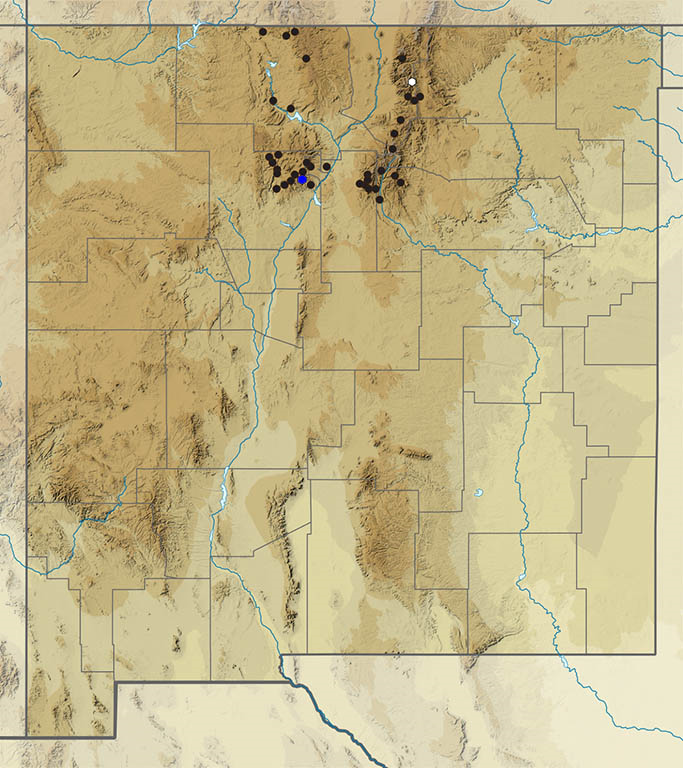

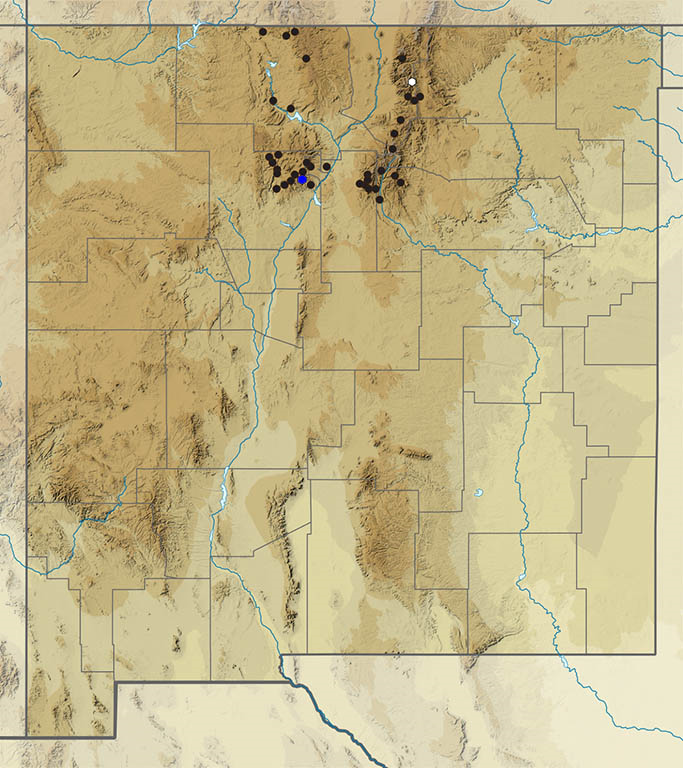

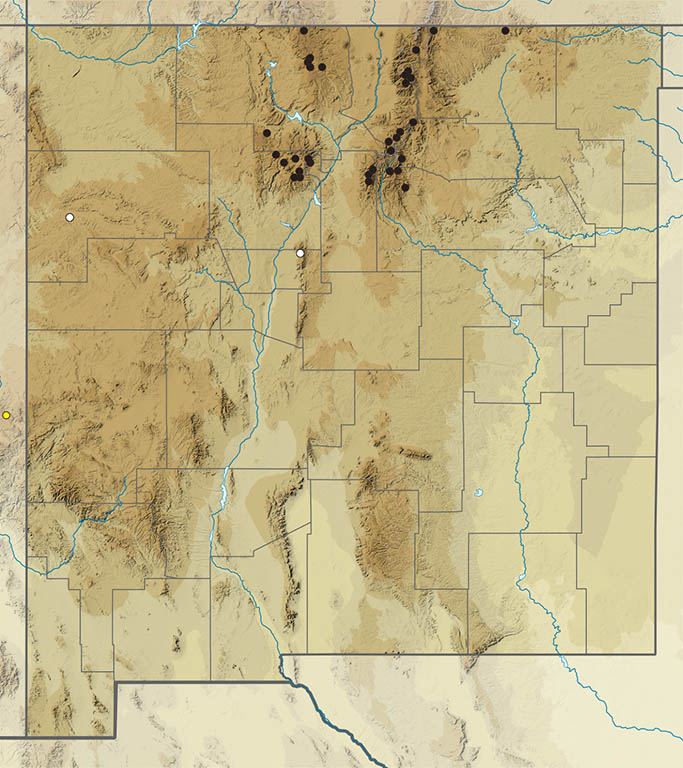

Occurrences of Arctic Fritillary (Boloria chariclea) in New Mexico.

Boloria myrina (Cramer 1777) Silver-Bordered Fritillary (updated July 2, 2023)

Description. Compared to its congeners, Silver-Bordered Fritillary has a diagnostic row of silver marginal spots on the hindwing underside. Also note the white-ringed black dot in the ventral hindwing basal area. On the upperside, wing submargins have inward-pointing triangles. Range and Habitat. This butterfly is Holarctic in distribution, occurring in high prairie, boreal and subarctic habitats. In North America, colonies are known south in the Rocky Mountains to a few northern New Mexico (counties: Co,RA,Sv) where, at the southern limit of its range, it strongly prefers wet meadow habitats, 8700 to 10,500′. Life History. Larvae eat violets (Violaceae) including Viola papilionacea (Ferris and Brown 1980), V. nephrophylla and V. glabella (Scott 1986). Half-grown larvae overwinter. Flight. New Mexico records for this univoltine butterfly fall between June 21 and August 12. Boloria myrina flies low, seeking nectar in its wet meadow homes. In 2002, Paula Kleintjes found a colony in the Valles Caldera National Preserve (Sv). In 2020, Steve Cary found a colony it at Eagle Nest Lake State Park (Co). Comments. Our colonies are grouped with subspecies Boloria myrina tollandensis (W. Barnes & Benjamin 1925), the typical Rocky Mountain race. For many years this species had been lumped with Old World Boloria selene ([Denis & Schiffermüller] 1775) but recent genetic studies have emphasized its distinctiveness.

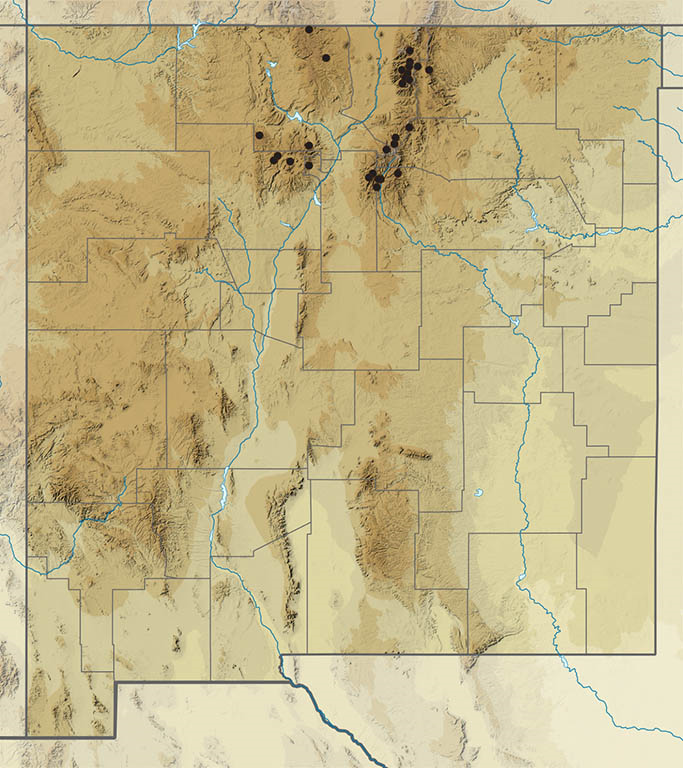

Occurrences of Silver-bordered Fritillary (Boloria myrina) in New Mexico.

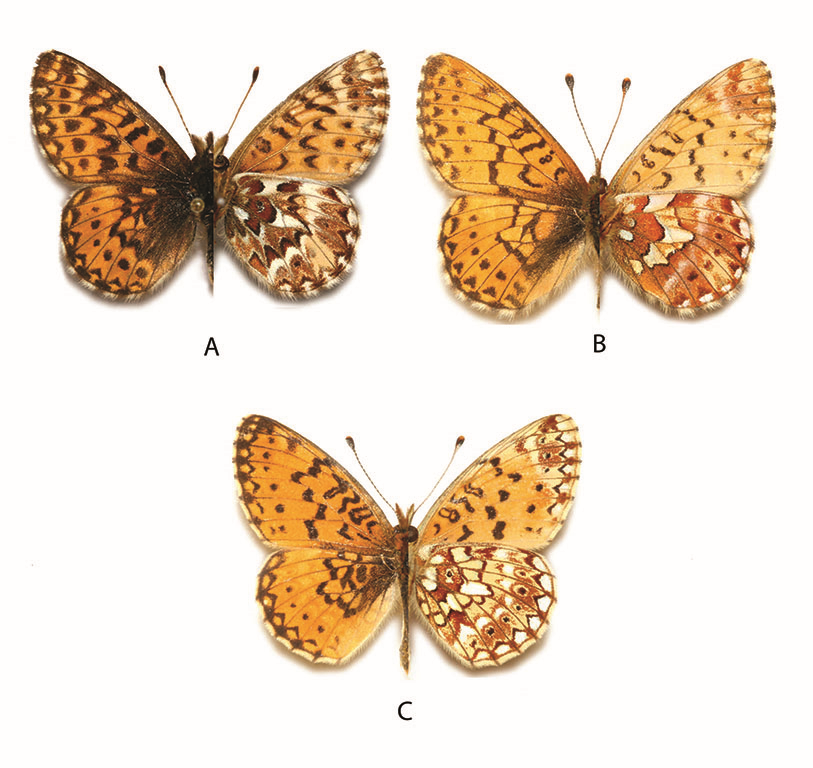

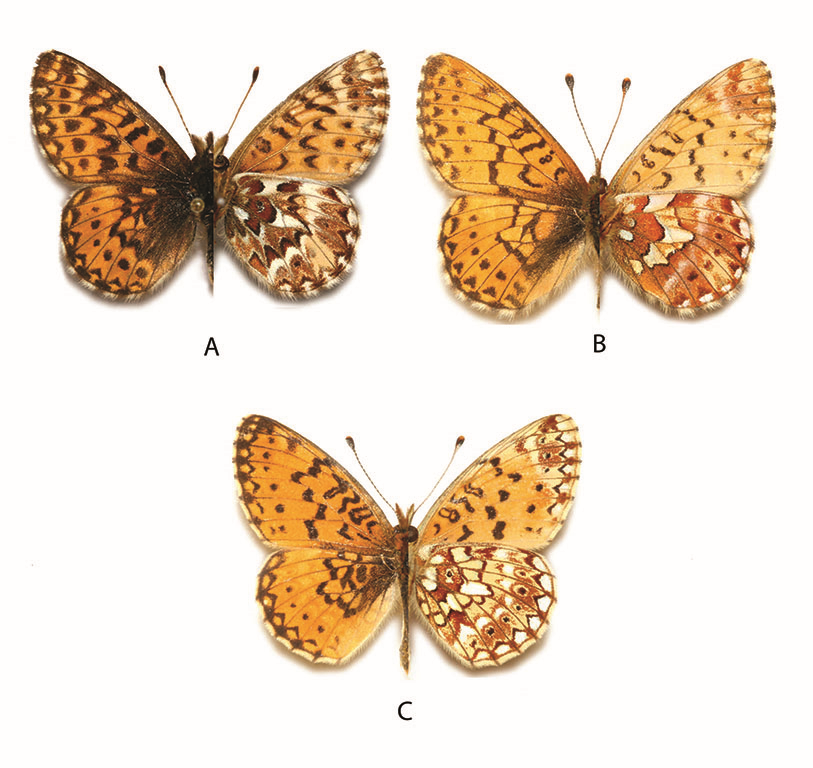

Comparison of “lesser” fritillaries (Boloria) found in New Mexico. A) Freija Fritillary (B. freija); B) Arctic Fritillary (B. chariclea); C) Silver-bordered Fritillary (B. myrina).

The Greater Fritillaries: Argynnis spp. Updated July 11, 2023.

The Greater Fritillaries (Argynnis spp.) have always attracted North American butterflyers because of their beauty, complexity, large size, and widespread occurrence. One consequence of this interest was a proliferation of named populations (56 “species” were recognized by Holland [1930]). Cyril dos Passos and L. P. Grey began to make order of this group with their 1947 paper, in which they recognized 109 valid names and reduced the number of species to 13. Recent work on morphology, genetics, ecology and distribution has led to the current situation (Zhang et al. Nov. 2020; Pelham 2023) of 19 species and 132 “valid” names for species and subspecies. In New Mexico, we are fortunate to have 7 species, with two more (idalia and callippe) with a chance to be found here. Several other species have been reported for the state, mostly erroneously.

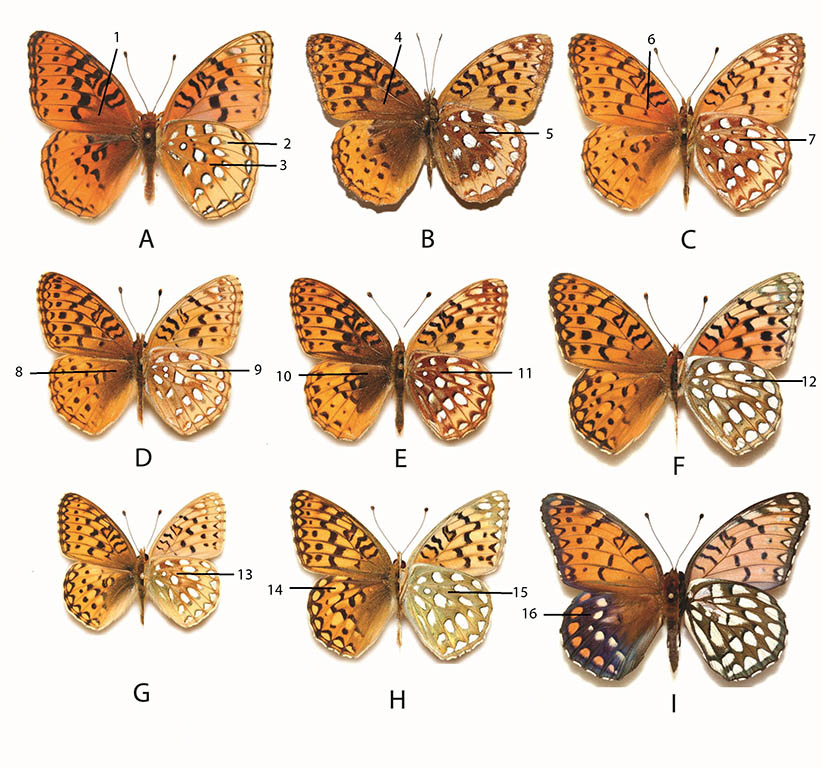

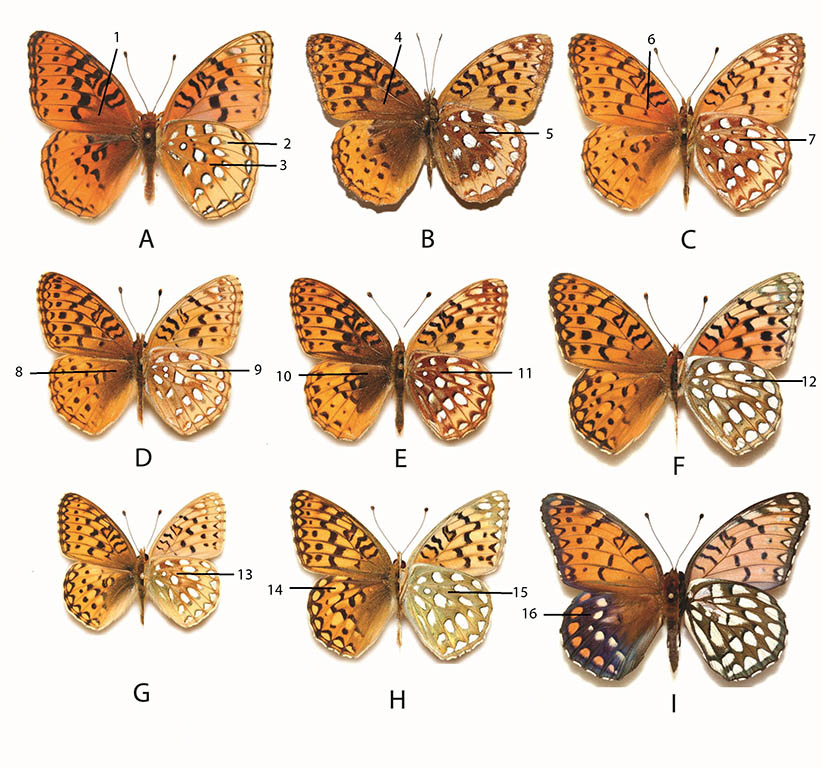

The close resemblance of the various Argynnis species to one another contributes to on-going uncertainties in this group. The figure below compares males of Argynnis found or likely to be found in New Mexico indicating useful characteristics for distinguishing species. Eye color is useful as well, but only in the wild or in photographs because that characteristic disappears in museum specimens. Females generally share the same distinguishing features, but in some species (A. nokomis for us) females are very distinct. Further research is required to sort out the remaining puzzles. Populations from Mount Taylor, Chuska Mountains, Jemez Mountains and New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains have not yet been sequenced, so stay tuned!

Argynnis nokomis W. H. Edwards 1862 Nokomis Fritillary, Great Basin Silverspot (updated July 4, 2023)

Description. The sexual dimorphism of this large butterfly, Nokomis, is amazing. Males resemble other Argynnis (Speyeria) species in size and maculation, although the dorsal ground color may be redder and the ventral ground color yellower. Females, in contrast, are blue-black dorsally, with whitish in the wide postmedian area. Below, females have a brown discal region and a pale greenish submargin. Eyes are brown. Range and Habitat. Also called Great Basin Silverspot, this butterfly occurs discontinuously in the Great Basin and surrounding uplands, south into northern Mexico. It inhabits wet meadows with the larval host. This habitat is scarce in the semi-arid west and southwest; colonies often are small, disjunct and vulnerable to degradation by human activities. Beaver activity once kept riverside habitats in good shape for Nokomis, but they have been eliminated from most of their former habitats. In New Mexico, the few remaining colonies of Argynnis nokomis are in the marshiest valleys in our wettest mountains (counties: Ca,Ci,Gr,Mo,Ot,SJ,SM,Ta), from 7000 to 9500′ elevation. Life History. The only known host is kidney-leaf violet (Viola nephrophylla; Violaceae), which thrives in emergent aquatic (up to ankle-deep) marsh habitats. Larvae hatch in autumn, overwinter, and begin feeding in spring. Flight. Argynnis nokomis has one late summer brood; New Mexico adults fly from July 13 to September 29, principally August. They go to nectar, but rarely stray far from their wet-meadow homes. Comments. This beautiful, hard-to-find insect has long been prized by collectors, some of whom keep colony locations secret. Sapello Canyon (SM) was the type locality of Argynnis nokomis nigrocaerulea W. Cockerell and T. Cockerell 1900 and aberration “rufescens” (Cockerell 1909). These were later synonymized with the nominate subspecies, to which northern New Mexico colonies are assigned based on recent DNA analyses. Western New Mexico colonies (Ca,Ci,Gr) belong to Mogollon Rim subspecies Argynnis nokomis nitocris (W. H. Edwards 1874). Validity and identity of Nokomis colonies in the Sacramento Mountains (Ot), now probably extirpated, has long been a topic of heated debate among the personal, private, passionate, even the published world of Nokomis lovers. Arizona collector Kilian Roever may have made the only collections of actual specimens from there, ever. Unfortunately, all that seems to remain of those specimens is a single photograph, which suggests it may belong with the Mexican subspecies, Argynnis nokomis coerulescens (W. Holland 1900). Richard Holland found specimens in the Carnegie Museum that were labeled from the Sacramentos (Holland 2010) and he named it ssp. tularosa, but DNA analysis showed the type was from the Sangre de Cristos, as predicted by Scott & Fisher (2014). One cannot do DNA analysis on a photo, so unless Nokomis is rediscovered in the Sacramentos, that may be the final word on what, if anything, once was there.

Argynnis cybele (Fabricius 1775) Great Spangled Fritillary (updated February 1, 2024)

Description. Argynnis cybele is large and majestic in the eastern US, and in the West it is second only to Nokomis. The upperside has dark basal suffusion. The cell above the posterior margin of the forewing lacks a black spot, which is present in most other fritillaries including Aphrodite. Below, the hindwing discal region is uniform red-brown, with a distinctively broad blonde band distally, very different from Aphrodite. The underside submarginal and postmedian bands of silver spots are small and well-separated. Eyes are amber/tan. Range and Habitat. Great Spangled Fritillaries are well-known inhabitants of open fields and woodlands in eastern North America. They also occur across the western cordillera to the Pacific Northwest and extend south into northern New Mexico (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF,Ta). Here they are insects of Transition and Canadian Zone damp meadows and sunny stream corridors within coniferous woodlands. Our records span 7800 to 11,000′ elevation. Life History. Larval hosts are violets (Violaceae), a characteristic of this entire genus. Reported host plants for this butterfly include Viola adunca, V. palustris, V. papilionacea, V. canadensis and V. rotundifolia. Young larvae pass the winter. Flight. In our area, Great Spangled Fritillaries have one generation per year, with adults in flight between July 7 and September 10. They like to nectar at flowers such as thistles (Cirsium spp.), spiked gayfeather (Liatris spicata), dogbane (Apocynum sp.), and cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata). Comments. Southern Rocky Mountain populations were traditionally assigned to subspecies Argynnis cybele carpenterii W. H. Edwards 1876, which was described from specimens collected by Lieut. W. C. Carpenter of the Wheeler Expedition, purportedly near Taos. However, genomic analyses reported by Zhang et al. (Feb. 2022) prompted those authors to conclude the type specimen for ssp. carpenterii was collected in Maine or Nova Scotia. That left our populations without a valid name, but Zhang et al. filled that void by describing A. cybele neomexicana from the Jemez Mountains. Unpublished 2023 analytical results of Sangre de Cristo Mtns. (NM) specimens showed them to be genomically consistent with A. cybele neomexicana Grishin 2022. Populations northwest of Chama (RA) show some possible intergradations with Colorado west slope subspecies A. cybele charlottii W. Barnes 1897.

Argynnis aphrodite (Fabricius 1787) Aphrodite Fritillary (updated July 6, 2023)

Description. Aphrodite has the basic Argynnis features, including a silver-spotted ventral hindwing. Rusty scales of the ventral hindwing discal area extend beyond the postmedian band of silver spots. On the upperside, it is distinguished by radiant orange above in males, reduced dark basal scaling, reduced black scaling on veins toward the back of the forewing, and little or no black on hindwing veins. Females are less bright and expanded dark marks. Eyes are brown. Range and Habitat. Like Argynnis cybele, this species is a familiar sight in the eastern US. Its greater distribution includes the Great Plains, the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains from British Columbia to New Mexico, and a population on the Mogollon Rim in central Arizona. Records of that population (ssp. byblis) come within 30 miles of our border, so observers might find it in Catron County when that high country is more thoroughly explored. In our state, Aphrodite lives in Transition Zone grasslands and pine savannas (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SJ?,SM,Ta,Un), typically between 6500 and 8200′ elevation. Life History. Larval hosts are violets (Violaceae). Hostplant species listed by Scott for Colorado (1986, 1992) include V. nuttalli, V. adunca and V. nephrophylla. There is no hostplant information specifically reported from our state, but the above reports probably hold true for northern New Mexico as well. Flight. Argynnis aphrodite has one generation per year. Adults fly in mid-summer between May 23 and September 17, with maximum numbers in July. This butterfly is passionately fond of nectar (e.g., Cirsium spp., Monarda fistulosa, and Asclepias tuberosa) and also visits wet soil, sometimes in numbers. Bright Aphrodite is reliably found on and near the Raton Mesa volcanic complex (Co,Un). At Sugarite Canyon State Park on July 15, 2010, Aphrodite adults siphoned nectar from Monarda, while Raton Mesa Fritillaries preferred Rudbeckia laciniata. Comments. Populations in northeast New Mexico (Co,Un) are most logically grouped with the Front Range race, Argynnis aphrodite ethne (Hemming 1933). Individuals from the Chama area and the Jemez Mountains (RA,SV), maybe even Gila high country (Ca), tend to be a little darker, not unlike individuals from western Colorado.

Argynnis hesperis W. H. Edwards 1864 Northwestern Fritillary (updated July 8, 2023)

Description. Northwestern Fritillary is smaller than Nokomis, Aphrodite and Great Spangled. It is bright orange above with bold black marks and slightly thickened, black veins on the forewing from costa to the back margin. Females have paler margins above. Compared to sister species, dorsal median and basal areas are only slightly smudged with dark scales. On the hindwing below, the pale arc in the postmedian area is narrow compared to Great Spangled. Its ventral hindwing white spots are almost always silvered, but an occasional individual with unsilvered white spots has turned up near Raton. Range and Habitat. Argynnis hesperis occupies Canadian Zone meadows and open woodlands from Alaska to Newfoundland and south in the Rocky Mountains into extreme northeast New Mexico, generally 7,500 to 9,500′ altitude. New Mexico’s only representative of this species, Argynnis (Speyeria) hesperis ratonensis J. A. Scott, was described from the Raton Mesa complex of Colorado and New Mexico (counties: Co,Un), where it maintains its very restricted distribution. There, it can be confused only with Aphrodite, which has amber/tan eyes compared to gray/blue eyes of the Raton Mesa Fritillary. Life History. Larvae eat violets (Violaceae), particularly Viola canadensis v. scopulorum on Raton Mesa (Co) (Scott 1992). Flight. Adults fly in one mid-summer generation, generally from June into September, peaking in July. They feed at flowers and wet sand. Comment. Zhang et al. (2020, Tax. Rep. Int. Lepid. Surv. 8(7): 17-19) , fig. 11, elevated nausicaa to species level, distinguishing it from hesperis.

Argynnis nausicaa W. H. Edwards 1874 Southwestern Fritillary (updated July 24, 2023)

Description. Southwestern Fritillary is of medium size. Dorsally males are bright orange with black lines, spots and chevrons; females are less bright. Underneath, the hindwing is red-brown in the discal region with a narrow post-discal blond band, all decorated by silvered white spots. Compared to Northwestern Fritillary, black markings are heavier on the upperside, particularly along DFW veins. Populations in north-central mountains have gray-blue eyes, unlike sympatric Aphrodite or Great Spangled. Populations south of I-40 and in the Sandia Mountains have amber-tan eyes. Both eye color morphs may occur in some areas. The ID challenge is simplified in southern populations where nausicaa is the only Argynnis species. Range and Habitat. Southwestern Fritillary inhabits the Intermountain West from Idaho and eastern Washington east to the Dakotas and south to Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. Here, it is the most widespread of our silver-spotted fritillaries, occupying mesic Transition and Canadian Zone conifer forests between 7,500’ and 10,000 feet elevation where violets thrive. As a consequence of New Mexico’s physiography, suitable habitats are isolated from each other by broad, unsuitable lowlands. As a result of isolation, multiple local regional populations have differentiated and are recognized as distinct subspecies. Life History. Larvae eat violets (Violaceae) such as Viola adunca, V. canadensis, V. purpurea, and V. nuttallii (e.g., Scott 1986). Oviposition on V. nephrophylla was observed in the Chuska Mountains (SJ) (Scott 1992). Flight. Adults are on the wing in one mid-summer generation, usually from June into September, peaking in July and early August. They feed greedily at flowers and wet sand. Comment 1. Recent elevation of Argynnis nausicaa to full species status by Zhang et al. (2020) seems to have fulfilled the prediction that this group, “when better studied . . . may prove to be a separate species” (Glassberg, 2017, p. 170). The moniker ‘Southwestern Fritillary’ is a placeholder English name until something better comes along, but we think it captures the essence of the beast. Comment 2: Individual subspecies are presented below . . .

Arizona’s White Mountains and Mogollon Rim along with the Gila/Mogollon high country of west-central New Mexico have the nominate subspecies, Argynnis nausicaa nausicaa W. H. Edwards 1874. This organism has a distinctive reddish cast on the upper side. The rust-colored discal region below is considerably invaded by blond scales. Adults have amber eyes. This variety also occurs in the Black Range and San Mateo Mountains (counties: Ca,Gr,Si,So), intergrading with Argynnis nausicaa dorothea in the Magdalena Mountains (So).

Subspecies Argynnis nausicaa dorothea (Moeck 1947) was described from collections on Sandia Peak. Pelham (2023) ascribes the “Sandia Peak” type locality to Sandoval County; it is in Bernalillo County, but northern footslopes do occur in Sandoval County. Darker than most other subspecies, Dorothea’s Frit inhabits the Sandia, Manzano, Mt. Taylor, Zuni (?) and Chuska ranges in central and northwestern New Mexico (counties: Be,Ci,MK?,Sv,SJ,SF,To). Intermediates with nominate A. n. nausicaa are found in the Magdalena Mountains and San Mateo Mountains (So). Mysteriously, adults in the Sandias and Manzanos have amber eyes, while adults in the Chuskas have grey-blue eyes. This makes us suspect we have more to learn about these fritillaries. Amber-eyed Dorothea’s are occasionally observed in Santa Fe County, suggesting possible northward dispersal from the Sandias.

The Capitan, Sierra Blanca and Sacramento Mountains (counties: Li,Ot) of south-central New Mexico host Argynnis nausicaa capitanensis (R. Holland 1988). This is our darkest race on the upper side, darker even than A. n. dorothea. It also has tan/amber eyes.

The Sangre de Cristo Mountains (counties: Co,Mo,RA,SM,SF,Ta) have subspecies Argynnis nausicaa electa W. H. Edwards 1878. For many years, the Jemez and Tusas Mountains (counties: LA,RA,Sv) were considered to have their own subspecies: Argynnis nausicaa nikias (Ehrmann 1917). This form was described from Jemez Springs (Sv) based on specimens collected by John Woodgate in the Jemez Mountains. Nowadays, Southwestern Fritillaries observed in the Jemez and Tusas Mountains are generally lumped with electa. Our records span June 5 to September 10. Adults have grey-blue eyes which is a bit of a head-scratcher.

One image below shows a very melanic (dark) aberration. Such oddities occur from time to time in any genetically well-mixed population.

Argynnis edwardsii Reakirt 1866 Edwards’ Fritillary (updated July 24, 2023)

Description. One of our most distinctive fritillaries, Argynnis edwardsii is large and bright with an elongated forewing. The greenish ventral hindwing has elongated silver spots that appear to be squeezed onto the wing. Eyes are grey-blue. Range and Habitat. Edwards’ is an inhabitant of the central Rocky Mountains and adjacent high plains from northern New Mexico to Alberta. It is a denizen of high prairies and savannas. Here, it occupies our north-central mountains and adjacent high mesas (counties: Co,RA,Sv,SJ,Ta,Un), 6500 to 10,000′ elevation. Life History. Viola nuttallii and V. adunca (Violaceae) are hosts elsewhere (Scott 1986). Newly eclosed larvae overwinter without feeding. Flight. This is our earliest-flying fritillary. Its long, single summer brood is on the wing between May 17 and August 22. Males patrol hilltops; flight is fast, furious and overhead, but hungry adults will come to earth for nectar. Comments. The oldest substantiated New Mexico record is credited to Mike Toliver, who observed it north of Folsom (Un) on 6 June 1971.

Argynnis bischoffii W. H. Edwards 1869 Bischoff’s Fritillary (updated July 27, 2023)

Description. Argynnis bischoffii is the smallest of our six ‘greater’ fritillaries, almost as small as the various Boloria species. Its dorsal black marks are fine, clear and distinct, not heavy like those of Argynnis hesperis or nausicaa, with which it sometimes flies. Its pale silvery-greenish ventral hindwing is diagnostic and its small, light, bright appearance reinforces that distinction. Eye colors seems to include pale blue, gray, hazel and even amber. Range and Habitat. This butterfly occurs north along the Cordilleran spine into Alaska and south in the Rocky Mountains to NM and AZ. In New Mexico it occupies boreal habitats straddling treeline in our higher northern mountains (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF,Ta), generally 8900 to 12,500′ elevation. Life History. Larvae eat violets (Violaceae). Use of Viola adunca, V. palustris, V. nephrophylla and V. nuttallii was reported by Scott (1986). Flight. Bischoff’s Fritillary is univoltine with adults about only during the brief summer warm season in its high-altitude home. New Mexico records fall between June 23 and September 12, peaking in July. Adults nectar at flowers and bask continually; they are immobilized when a cloud covers the sun. Comments. Our known colonies belong to Rocky Mountain subspecies Argynnis bischoffii eurynome (W. H. Edwards 1872). The earliest NM observations were made near Spring Mountain (SM) by a party associated with Prof. F. H. Snow in 1881. There is one report of Argynnis bischoffii from Sandia Crest (Be), but the documentation is vague and verification is needed before it can be accepted. Similarly, an old specimen sent east from Fort Wingate (MK) probably was not collected there. It is possible that the Arizona subspecies, Argynnis bischoffii luski W. Barnes & McDunnough 1913, will be found in Catron County, as there are recent records of this subspecies within 15 miles of NM. Bischoff’s Frit was previously considered a subspecies of A. mormonia, but DNA work by Zhang, et al (2022) indicated that bischoffii and its associated subspecies are distinct. True mormonia is apparently limited to the West Coast.

Argynnis idalia occidentalis (B. Williams 2002) Regal Fritillary (added July 29, 2023)

Description. Argynnis idalia is the most distinctive ‘greater’ fritillary. On the upper surface, the dark hindwing with a curving band of postmedian white spots stands out – especially as it contrasts with the orange forewing. No other fritillary (indeed, no other large North American butterfly) sports such a combination. Beneath, the silver spots on the hind wing are conspicuous and large, covering most of the hindwing. Range and Habitat. If one was looking for an indicator species for high-quality prairie, one could do no better than the Regal Fritillary. The species used to be distributed from the NE US to the Rockies, but it has largely disappeared from most habitats east of the Mississippi River. It is still common in fertile habitats west of the Mississippi, but many of those are rapidly disappearing. Life History. Larvae eat violets (Violaceae), especially Bird’s Foot (Viola pedata). The female lays eggs one at a time on low vegetation near the host plant. Newly hatched larvae don’t eat, overwintering until the following spring when they begin to feed on their hosts. Flight. The Regal Fritillary is univoltine, with adults appearing from June to August. Comments. The Regal Fritillary is one of the most sought-after fritillaries because of its great beauty and scarcity. Dick Holland thought he spotted an idalia-like butterfly at Clayton Lake State Park on 13 August 1996 but was unable to capture it. There are verified records of the species from Baca County, CO, within 30 miles of NM.

Argynnis callippe Boisduval, 1852 Callippe Fritillary (added July 23, 2024)

Description. Callippe is similar to the Southwestern Fritillary, with similar makings on the upper surface. However, Callippe typically is lighter and the postmedian row of spots on the hind wing is more prominent. The real clues lie on the under surface: Callippe has a grey-green color dominating that surface, as opposed to the brown of Southwestern. The postdiscal band is narrow in Callippe and the silver spots are larger. Range and habitat. Callippe is a western species, found from California north through Oregon and Washington east of the Cascades, east to Saskatchewan and south to southern Colorado. It has yet to be found in New Mexico. Life history. Larvae feed on various Violet species, including Viola nuttallii. Flight. This species is often the earliest of the large Fritillaries to appear, flying from May – September in Colorado in a single brood. Comments. Should this fritillary be found in New Mexico, the likely subspecies would be Argynnis callippe meadii W. H. Edwards 1872. There is an historical record of this critter from Montezuma County, Colorado, just over the border from New Mexico, and there are recent records from Ouray County and Pueblo County, about 60 miles north of our border.

Greater Fritillaries unreliably reported from New Mexico.

Several other species of Argynnis have been reported for our state, most likely erroneously. The most interesting of these unconfirmed reports is dos Passos and Grey’s 1945 description of Argynnis hydaspe conquista from Little Tesuque Canyon, Santa Fe County, and from Therma, Eagle Nest, Colfax County, based on specimens collected by Klots in 1932. Despite numerous attempts to locate this species, no other specimens have been found in New Mexico. The name conquista has been regarded as a synonym of Argynnis hydaspe rhodope W. H. Edwards 1874, from Wyoming. The closest approach of hydaspe to NM is more than 200 miles away in NW Colorado. Klots was a careful scientist, and Mike Toliver’s correspondence with him indicated his firm belief that conquista had been collected in Little Tesuque Canyon; nevertheless, it seems likely that the specimens were mislabeled. BAMONA still lists “New Mexico” as the southern terminus of hydaspe distribution, which we believe is in error.

Dos Passos and Grey (1947) reported A. zerene platina from NM, an unlikely occurrence. The closest zerene approaches NM is in Gunnison County, CO, almost 100 miles north of the NM border. Miller (1961) reported Argynnis callippe and zerene from Red River (Ta): “At Red River in Taos Co., at almost 8900 ft, in late August, he found good collecting: Speyeria aphrodite, calIippe. mormonia and zerene.” It seems likely that these reports of callippe and zerene were mis-determinations. Callippe is reported from Pueblo Co., CO, about 65 miles north of NM, on iNaturalist, and there is a historic record of this species from La Plata County just north of the NM border on the BAMONA web site. A. coronis approaches NM as well, again about 100 miles north of our border, but it has not been reported by anyone to our knowledge. Dick Holland spotted an idalia-like Nymphalid at Clayton Lake State Park in Union Co. At least callippe and idalia are likely to be found in NM with more exploration of our northern border and northeast plains. Unfortunately, mis-determinations abound in this complex and taxonomically dynamic group.