by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver (updated December 23, 2023)

The Brushfoots (Nymphalidae). This family is our second richest in terms of number of species and perhaps the most variable in terms of sizes, colors, patterns and behaviors. Despite the obvious differences in wing morphology, almost all members share a unifying structural character: on adults, the forelegs are reduced to tiny, brush-like structures, leaving only four functional legs. The exception that proves the rule is female Libytheinae, which have functional forelegs, emphasizing their ancestral status. Many of our most familiar butterflies are members of this family. Pursuant to Pelham’s (2023) catalog, we have ~100 species in ten subfamilies distributed as shown below. Other works may arrange, lump, or divide families in other ways.

Satyrs and Wood-Nymphs (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae). Within the large family of brush-footed butterflies, what sets this subfamily apart? Larvae of these tan, brown and black butterflies specialize on eating grasses and sedges. We have 19 species, some in our harshest habitats. Most perch and bask with their wings folded. In that posture, most are the size of a quarter or half-dollar.

- Common Ringlet (Coenonympha california) tullia, ochracea, subfusca

- Nabokov’s Gemmed-satyr (Cyllopsis pyracmon henshawi) nabokovi

- Canyonland Gemmed-satyr (Cyllopsis pertepida dorothea) maniola, avicula

- Red Satyr (Cissia rubricata) Cissia rubricata smithorum, Megisto

- Southwest Red Satyr (Cissia cheneyorum)

- Red-bordered Satyr (Gyrocheilus patrobas tritonia)

- Common Wood-nymph (Cercyonis pegala) boopis, ino, texana

- Mead’s Wood-nymph (Cercyonis meadii) alamosa, melania, mexicana

- Great Basin Wood-nymph (Cercyonis sthenele masoni)

- Small Wood-nymph (Cercyonis oetus charon)

- Colorado Alpine (Erebia callias)

- Magdalena Alpine (Erebia magdalena)

- Common Alpine (Erebia epipsodea brucei)

- Uhler’s Arctic (Oeneis uhleri reinthali)

- Ridings’ Satyr (Oeneis ridingsii) Neominois ridingsii, neomexicanus

- Melissa Arctic (Oeneis melissa lucilla)

- Polixenes Arctic (Oeneis polixenes brucei)

- Chryxus Arctic (Oeneis chryxus) alticordillera, socorro

- Alberta Arctic (Oeneis alberta) capulinensis, daura

Coenonympha california Westwood [1851] Common Ringlet (updated June 15, 2024)

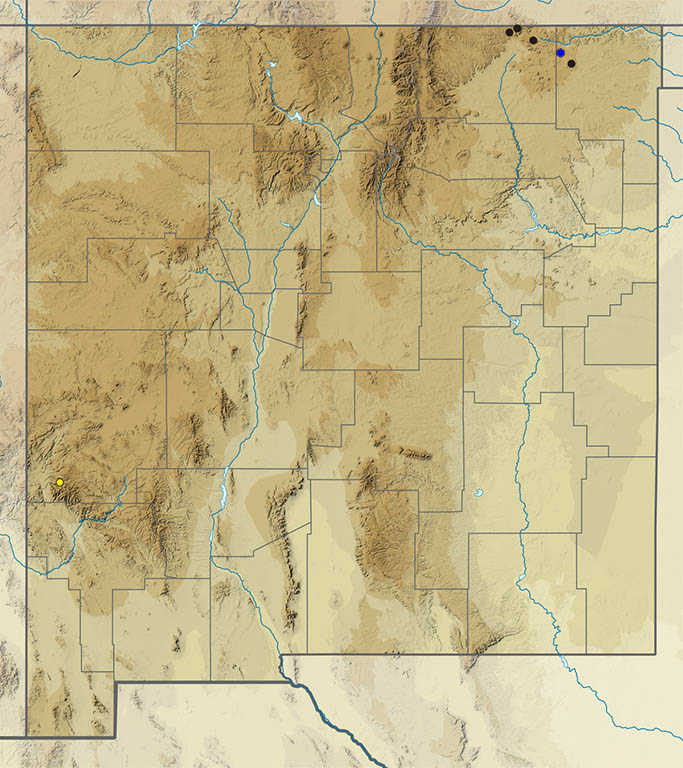

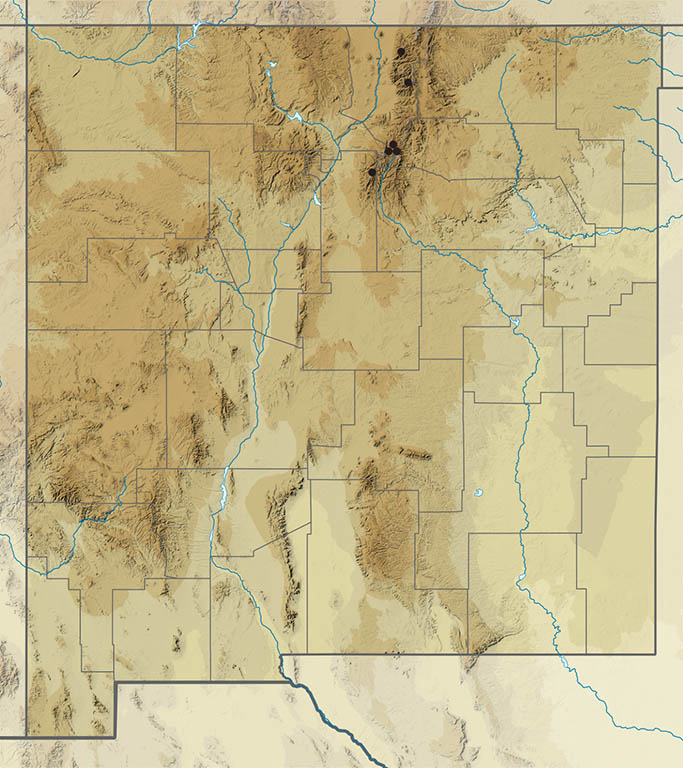

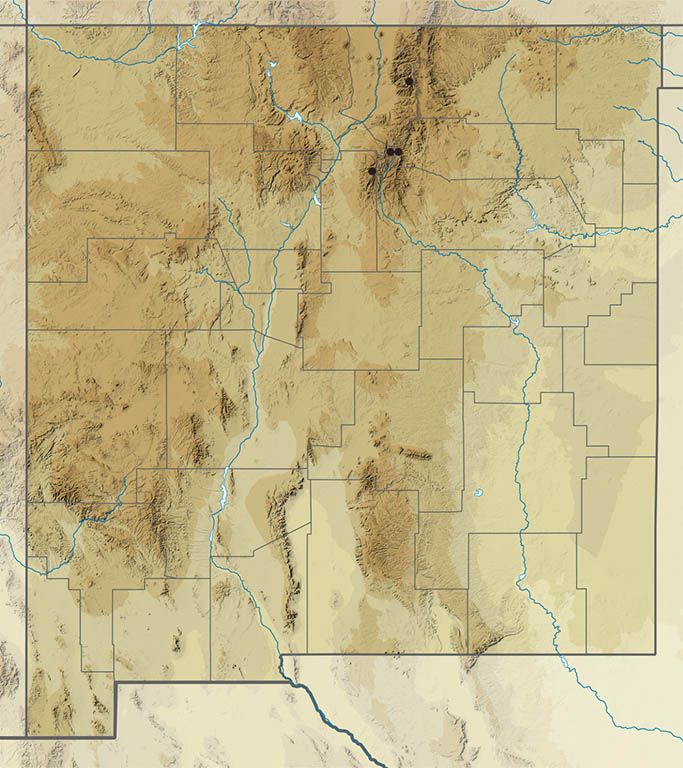

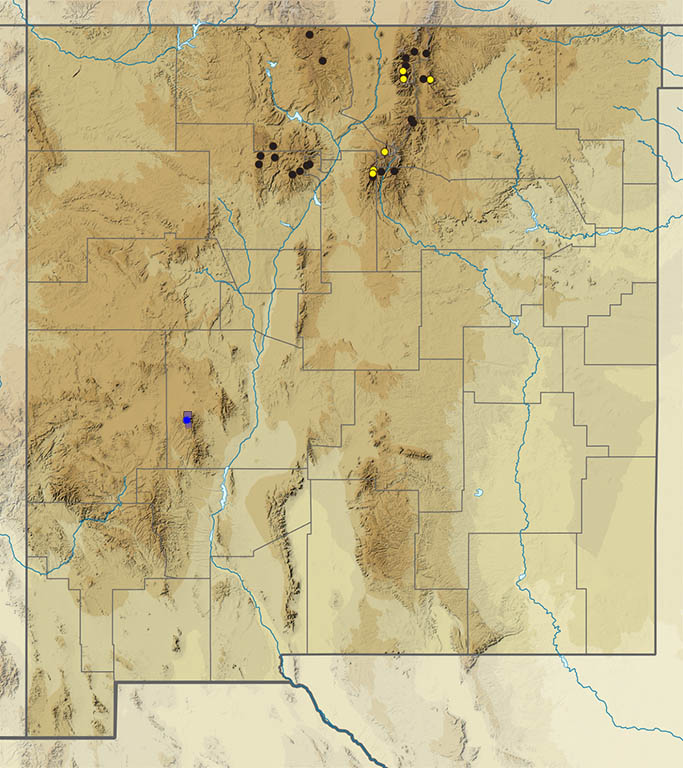

Description. This thumbnail-sized butterfly is bright tawny above. There is a prominent eyespot at the FW apex. Undersides are light ochre with hoary accents. The ventral hindwing has 0 to 6 eyespots or ocelli, variably developed. Range and Habitat. Common Ringlets live in temperate, arctic and subarctic North America, from Alaska to Newfoundland and south to California, Arizona and New Mexico. In our state it dwells on higher grassy mesas and mountains (counties: Be,Ca,Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SJ,SM,Ta,To,Va), 7000 to 11,000′. Life History. Females oviposit on or near several grasses and sedges, including Stipa comata, Poa pratensis, Festuca arizonica, F. idahoensis, Bouteloua gracilis (all Poaceae), and Carex pennsylvanica heliophila (Cyperaceae) (Scott 1992). Partially grown larvae overwinter. Flight. We have one summer flight spanning June and July, with extreme dates of April 24(!) and August 8. Adults fly near the ground and feed at nectar and wet soil. Comments. Based on genomic studies by Zhang et al. (2020), this and several other related subspecific North American taxa were removed from Coenonympha tullia (Müller 1764) and placed with Coenonympha california. Most New Mexico populations are the ‘Ochre’ Ringlet, Rocky Mountain subspecies C. c. ochracea (W. H. Edwards 1861), whose ventral hindwing ocelli very from few to absent. The population on the Mogollon Rim (Ca) and into east-central Arizona is subspecies C. c. subfusca (W. Barnes and Benjamin 1926), which consistently has six prominent, yellow-ringed, ventral hindwing ocelli.

Cyllopsis pyracmon (Butler [1867]) Nabokov’s Gemmed-satyr (updated December 20, 2023)

Description. Two ebony jewel boxes decorate the ventral hindwing margin of this and the next species, which are the size of a US quarter with wings folded. On Nabokov’s Gemmed-satyr, the ventral hindwing postmedian line is straight all the way to the costa and does not touch the silver-gray patch around the jewel boxes. Range and Habitat. Cyllopsis pyracmon is a Mexican species whose range extends northward into to southeast Arizona and southwest New Mexico. NM has records for the Peloncillos (Hi) and Pinos Altos (Gr). Look for it in higher, wetter canyons in our southwestern counties (Ca,Gr,Hi,Lu,Si), preferably above 5000 feet elevation. Life History. Larvae eat Muhlenbergia emersleyi (Poaceae) in Arizona. Flight. Nabokov’s Gemmed-satyr is bivoltine: the first brood flies in June; the second in September – October. Adults dodge among bunchgrasses on shrubby, shady canyon bottoms. Comments. New Mexico and Arizona have northern subspecies Cyllopsis pyracmon henshawi (W. H. Edwards 1876). Miller (1974) described Cyllopsis pyracmon nabokovi from Arizona (including specimens from “High Rolls, Otero County, NM” in the type series) and considered henshawi to be a separate species. That view prevailed for years, though some suspected that the two were merely seasonal forms. Recent work (e.g., Brock & Kaufman 2003) has confirmed that suspicion, thus nabokovi is now considered a synonym (late season form) of ssp. henshawi. Old reports from farther north in New Mexico (Ot,Sv) are highly suspect. Old specimens (including the paratypes of nabokovi) bearing labels from “High Rolls” are likely mislabeled. The current known range does not include any localities north of the Mogollon Rim or east of the Rio Grande.

Cyllopsis pertepida (Dyar 1912) Canyonland Gemmed-satyr (updated December 20, 2023)

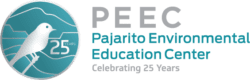

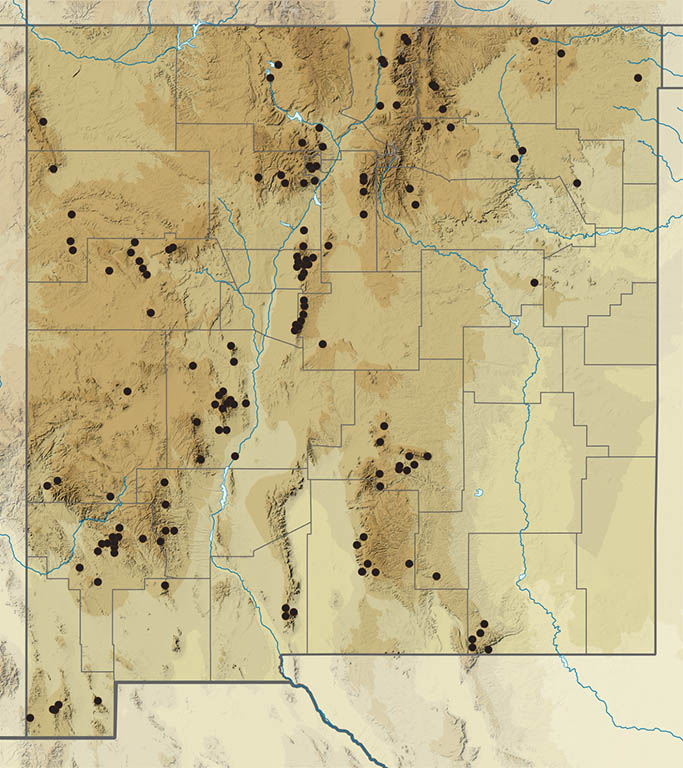

Description. This, our more widespread “gemmed” satyr, has a ventral hindwing postmedian line that is curved or irregular, disappearing near the hindwing apex. Upper sides are rusty brown in the most common form in NM. Range and Habitat. Canyonland Gemmed-satyr lives in much of the southwest US and Mexico. It prefers Upper Sonoran and Transition Zone grassy canyons and savannas in much of New Mexico (all counties but Cu,DB,Le,Ro,Qu), 4600 to 8900′. Life History. Larvae eat unknown grasses, then overwinter partially grown. Flight. Canyonland Gemmed-satyrs are bivoltine in northern New Mexico, with peak numbers in June and August. Three broods fly in southern New Mexico, peaking in May, July and October. Extreme dates are April 16 and November 13. Adults flop among canyon-side grasses, trees and shrubbery. They rarely visit flowers but are known to feed at mud and tree sap. Comments. Snow (1883) collected this species in the Magdalena Mountains (So) in 1881 but misidentified it as Cyllopsis pyracmon. Subspecies Cyllopsis pertepida dorothea (Nabokov 1943) prevails in most of (maybe all of) New Mexico. Subspecies Cyllopsis pertepida maniola (Nabokov 1943) has a gray ventral hindwing and enters our far southwest corner (Hi) and possibly other southwest counties (Ca,Gr,Lu,Si,So). Bailowitz & Brock (2021) speculated that maniola may be a separate species because it co-occurs with ssp. dorothea in several southeast AZ mountain ranges. Texas subspecies Cyllopsis pertepida avicula (Nabokov 1943) has a reddish ventral hindwing and enters our southeast corner (DA) and possibly other southeast counties (Ch,Ed,Ot). It, too, co-exists with ssp. dorothea in New Mexico. Vladimir Nabokov, renowned author and equally renowned lepidopterist, was particularly fond of this species and studied it extensively.

Cissia rubricata (W. H. Edwards 1871) Red Satyr (updated December 21, 2023)

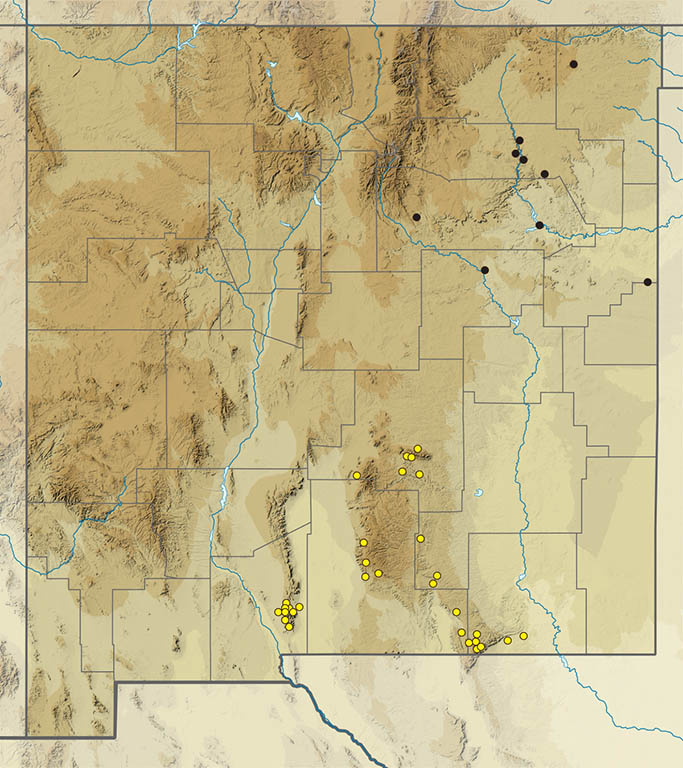

Description. Red Satyr has a gray-tan underside crossed by a distal band with three (one forewing, two hindwing) eyespots and small silver spots, variably expressed. Wing uppersides have an orange-red flush with a prominent eyespot on each wing. Range and Habitat. This quarter-sized Mexican satyr breeds northward into New Mexico, OK and TX. In New Mexico it lives in Upper Sonoran grasslands in southern and eastern areas, generally below 6000’ but straying as high as 8000′. Life History. Unknown grasses (Poaceae) are hosts. Half-grown larvae hibernate. Flight. Red Satyrs are univoltine. In our east-central counties it flies June 15 to July 31. In our southern counties, an extended flight spans April 29 to August 28, peaking in June to July. Adults dodge among grasses. Comments. This butterfly was recently removed from the genus Megisto and placed in Cissia (Pelham 2019). Even more recently (Zhang et al., 2022) subspecies cheneyorum was elevated to a full species (see below). Red Satyr’s nominate subspecies occupies eastern New Mexico (counties: Cu,Gu,Ha,Mo,Qu,SM,Un); it has extensive dorsal forewing red, but weak ventral ocelli. The Trans-Pecos area (counties: Ch,DA,Ed,Li,Ot) has vivid Cissia rubricata smithorum (Wind 1946), whose dorsal red is extensive and vibrant, while ventral ocelli are resplendent.

Cissia cheneyorum (R. Chermock 1949) Southwest Red Satyr (updated December 23, 2023)

Description. Southwest Red Satyr is very similar to Red Satyr, but the marks are comparatively subdued; the dorsal red areas are smaller and ventral ocelli are modestly expressed. Range and Habitat. Cissia cheneyorum lives in northern Mexico extending northward into Arizona and southern New Mexico west of the Rio Grande (counties: Ca,Gr,Hi,Lu,Si,So). In our state it inhabits Upper Sonoran grasslands generally below 6000’ but straying as high as 8000′. Life History. Grasses (Poaceae) are hosts, but specifics remain unknown. Half-grown larvae hibernate. Flight. Southwest Red Satyrs are univoltine. An extended flight spans May 1 to August 8, peaking in June to July. Adults dodge among grasses, but rarely visit flowers. Upon landing, adults often flick their wings once or twice before settling down. Their dorsal basking occasionally brightens up an early morning or a cloudy afternoon. Comments. Zhang, et al. (2022) used genomic and phenotypic characters to extricate cheneyorum from Cissia rubricata and elevate it to full species status. This is the latest example of the north-south Rio Grande Rift functioning as a significant barrier to east-west gene flow and thus a significant driver of speciation in butterflies. The Los Angeles County Museum has a specimen of Cissia cheneyorum from Silver City, captured 6 June 1949 by a young Harrison Schmitt, later an astronaut and U. S. Senator representing New Mexico.

Gyrocheilus patrobas (Hewitson 1862) Red-Bordered Satyr (updated December 19, 2023)

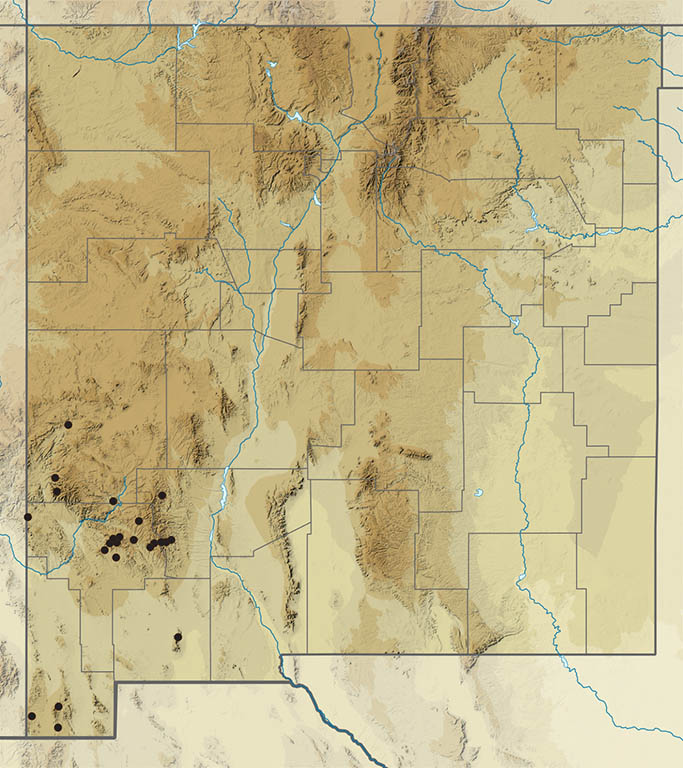

Description. Gyrocheilus patrobas is a large, dark species with scalloped wing margins. The HW has a marginal band that is red above and striated pink below, sometimes with a shockingly blue tinge. The forewing has a submarginal row of small white dots. There is absolutely nothing else like it in New Mexico – as Bailowitz & Brock (2021) note: “breathtaking!” Range and Habitat. Red-Bordered Satyrs inhabit Transition and Upper Sonoran Zone savannas in the Mexican Sierra Madre northward to the Mogollon Rim in Arizona and New Mexico. In our state it prefers open piñon-juniper woodlands in our southwest uplands (counties: Ca,Gr,Hi,Lu,Si), 4500 to 8200′. Life History. Muhlenbergia emersleyi (Poaceae) is a larval host in southeast Arizona (Bailowitz and Brock 2021). Flight. Red-Bordered Satyrs have one generation per year, flying in late summer to early autumn. New Mexico observations fall between late August and October 15, making it one of our latest-emerging univoltine butterflies. Adults bob and weave deceptively among grasses and shrubs, often near edges of riparian canyons. They come to nectar and damp sand. Comments. Subspecies Gyrocheilus patrobas tritonia W. H. Edwards 1874 lives in our area. Our first reports of this Sierra Madrean butterfly were made by John Hubbard in the Pinos Altos Mountains (Gr) in the late 1950s.

Cercyonis pegala (Fabricius 1775) Common Wood-Nymph (updated December 27, 2023)

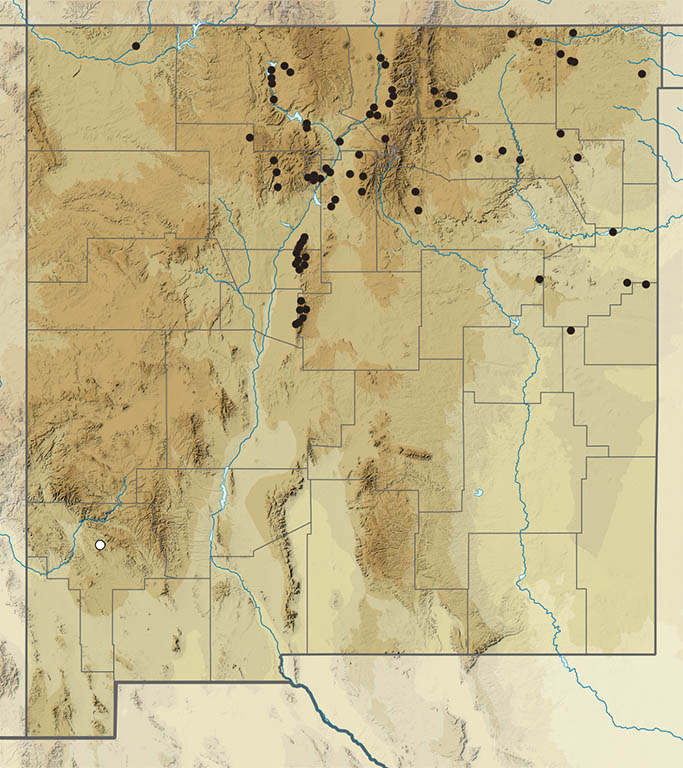

Description. Larger than all other Cercyonis found in NM, Common Wood-Nymph is brown with two prominent eyespots on the forewing above and below. Ventral hindwings often have a submarginal row of eyespots set against a background of fine scrollwork. Range and Habitat. From coast to coast and from southern Canada to California, New Mexico, Texas and Florida, Cercyonis pegala is a frequent mid-summer sight in meadows, grasslands, prairies and savannas. In northern New Mexico it occupies Upper Sonoran Zone grasslands, preferring edges of damp watercourses (counties: Be,Ca,Co,Cu,Gr,Gu,Ha,LA,Mo,Qu,RA,Ro,Sv,SJ,SM,SF,Ta,To,Un,Va), 5000 to 7400′. Life History. Eggs hatch in summer and first instars diapause through winter before getting busy eating grasses (Poaceae): Poa pratensis (usually the “native” ssp. agassizensis) is a favorite), often Schedonorus (Festuca) arundinacea, sometimes Bromus (Bromopsis) inermis, Elymus lanceolatus, Muhlenbergia montana, Schizachyrium scoparium, and Carex praegracilis (Cyperaceae). Flight. Common Wood-Nymphs are univoltine with peak flight in July and August. Records fall between May 21 and September 10. Adults appear to lurch and bob awkwardly through grasses and shrubs. Adults visit flowers of all colors, but will also feed at sap, mud, scat and other non-floral sources. Adults seem to live a relatively long time, up to several weeks, even roosting communally and estivating through summer dry spells elsewhere in the US. Comments. Eighteen subspecies have been described for this wide-ranging and variable butterfly. Opinions vary as to which subspecies carry on in New Mexico. The race in New Mexico’s central mountain chain has somewhat subdued underside markings and may be West Coast subspecies C. p. boopis (Behr 1864) or subspecies C. p. ino G. Hall 1924. Our northeast plains populations can have prominent ventral hindwing ocelli and forewing ocelli set in a vivid yellow patch, as in Texas subspecies C. p. texana (W. H. Edwards 1880). Phenotypic intermediates are almost the norm for this species. A specimen collected by Winslow Howard c. 1882 (Cockerell 1899) showed that Silver City, in southwest New Mexico (Gr) once had a population of Common Wood-Nymphs as well, but there have been no subsequent reports from that area.

Cercyonis meadii (W. H. Edwards 1872) Mead’s Wood-Nymph (updated December 28, 2023)

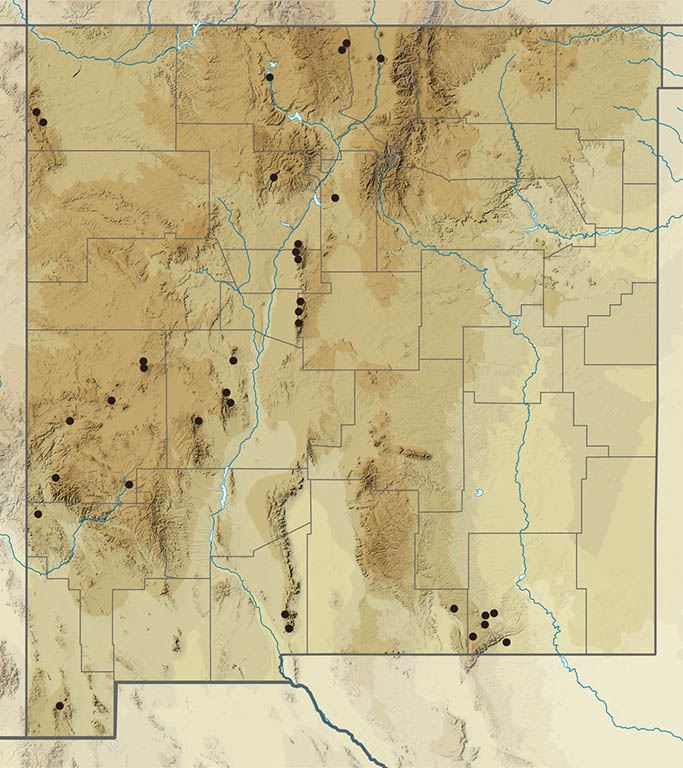

Description. Mead’s Wood-Nymph is largely brown with fine striations, but you have to admire the diagnostic ember-red overscaling on the forewing, above and below. There are two prominent, usually equal-sized, ocelli on each forewing; each has a white “pupil” and a black iris surrounded by a pale, yellow ring. Smaller ocelli punctuate the hindwing. Range and Habitat. Cercyonis meadii lives in or near the Cordilleran chain from Montana and North Dakota south to northern Mexico and west Texas. Though widespread, it is never common and seems most attached to blue grama savannas showing minimal human influence. Mead’s Wood-Nymph prefers piñon-juniper savannas in New Mexico (counties: Be,Ca,DA,Ed,Gr,Hi,RA,Sv,SJ,So,Ta,To), generally 4600 to 7000′ elevation. Life History. According to Scott (2022), hostplants in Colorado for ssp. meadii include Carex rossii (Cyperaceae) and Bouteloua gracilis (Poaceae). Ssp. alamosa is associated with Bouteloua gracilis, Sporobolus airoides (both Poaceae). Bailowitz & Brock (2021) noted oviposition on Piptochaetum fimbriatum (also Poaceae) in Chihuahua, Mexico (this may be ssp. mexicana). Females generally oviposit in litter near semi-shaded hosts. Unfed 1st-stage larvae hibernate. Flight. Cercyonis meadii is univoltine with adults about from July 14 to September 2 in northern New Mexico, and from June 30 to October 6 in southern New Mexico. Adults fly in grassy sage flats or open, grassy woodlands, searching for mates and coming readily to nectar. Comments. This species is named to honor prolific Rocky Mountain frontier naturalist Theodore Luttrell Mead. There are four named subspecies and NM could have all of them, but they seem poorly differentiated from a phenotypic standpoint. The nominotypical versions have no white “frosting” on the underside and VHW ocelli are few, small and not prominent. Examples from central New Mexico generally seem to fit that description. Populations in and around Colorado’s San Luis Valley, including New Mexico’s Taos Plateau, can be like that, too, but some have a white frosting or suffusion on the underside which is more like Cercyonis meadii alamosa T. Emmel and J. Emmel 1969, whose whiter underside may improve camouflage in the alkali soils typical of parts of the San Luis Valley. That extra white marginal and submarginal grizzling also occurs in C. meadii populations in the white limestone/dolomite bedrock of the Guadalupe Mountains (Eddy County, NM, Culberson Co., TX) where VHW ocelli also are more numerous and more prominent. Prominent VHW ocelli are consistent with ssp. C. m. melania (Wind 1946), but the white ventral grizzling is not consistent based on examples of melania shown on the Butterflies of America website. Individuals from the SW part of NM (Ca,Gr,Hi,So) might be classed with Cercyonis meadii mexicana (R. Chermock 1949). Mead’s Wood-Nymphs in northwest New Mexico (San Juan Co.) show evidence of introgression (= past hybridization) with Cercyonis sthenele (next species). Richard Holland took a female C. meadii mating with a male C. pegala in the Sandia Mts., further indicating the “mixed-up” nature of Cercyonis in NM!

Cercyonis sthenele (Boisduval 1852) Great Basin Wood-Nymph (updated December 29, 2023)

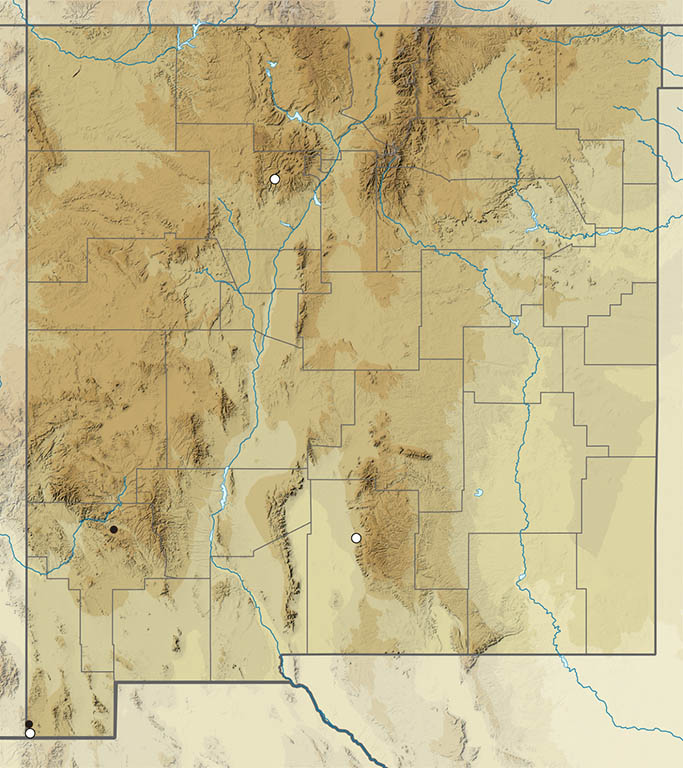

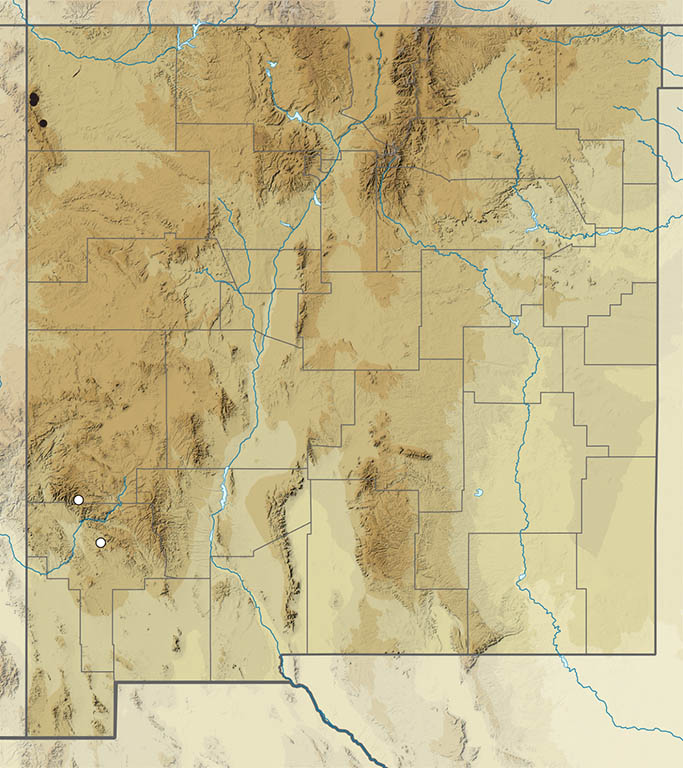

Description. Cercyonis sthenele is characterized by medium size and medium brown to pale brown color with two prominent, equal-sized, forewing ocelli; separating it from the somewhat similar Small Wood-Nymph (C. oetus). Great Basin Wood-Nymph’s ventral hindwing has distinctive submarginal ocelli that are black with white pupils. Range and Habitat. This butterfly lives in Great Basin deserts and chaparral west to California and Baja. It is an Upper Sonoran to Transition Zone insect barely reaching into our northwest corner on the Navajo Nation (counties: SJ), 5500 to 7200′. Reports from the Pinos Altos Mountains and Mogollon Mts. (Ca,Gr) are unsubstantiated (Zimmerman 2001; Hubbard 1965). Life History. Larvae eat unknown grasses. Flight. Great Basin Wood-Nymphs have one generation per year that is on the wing from July into September, peaking in August. Comments. GBWNs that enter New Mexico are part of Four Corners subspecies Cercyonis sthenele masoni Cross 1937. Individuals with a forewing red flush turn up with enough regularity to suggest past or ongoing interbreeding with Cercyonis meadii. Richard Holland made the first New Mexico observation on 28 July 1974 near Toadlena (SJ).

Cercyonis oetus (Boisduval 1869) Small Wood-Nymph (updated December 29, 2023)

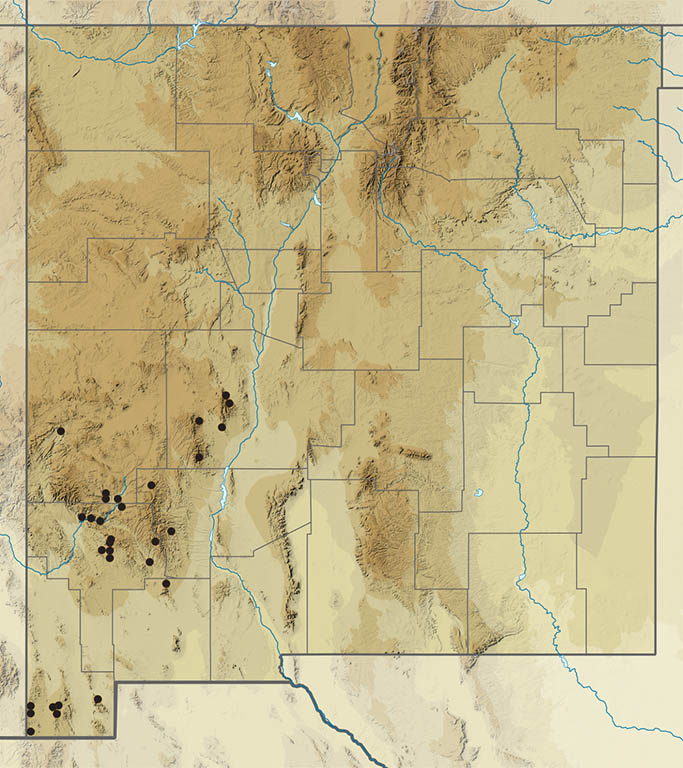

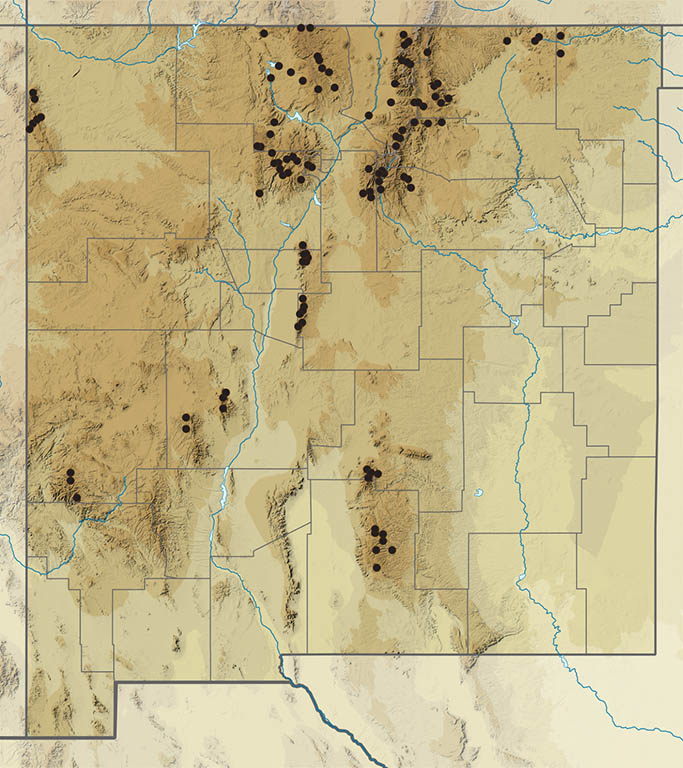

Description. This, our smallest Cercyonis, is dark brown above and below, with two yellow-ringed ocelli in the forewing postmedian region. The lower ocellus is always substantially smaller than the upper ocellus – a distinctive feature of this species in NM. Ventral hindwing eyespots are not prominent. Dorsal forewings may have one or two muted ocelli. The wiggle of the VHW postmedian line is distinctive. Range and Habitat. Cercyonis oetus is native to Transition and Canadian Zone grasslands of western North America, from British Columbia to Saskatchewan and south in the mountains to California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. Here, it occupies grasslands and savannas in northern and upland areas (counties: Be,Ca,Co,Li,LA,Mo,Ot,RA,Sv,SJ,SM,SF,So,Ta,To,Un), generally 6500 to 10,200′. Life History. Larvae eat grasses (Poaceae). Festuca idahoensis, a host in western Colorado, is widespread in New Mexico mountains and is a likely host here. Mature larvae crawl up grass stems and pupate there. Flight. Small Wood-Nymph has one annual generation. Adults fly between June 16 and September 26, peaking in July and August. Adults nectar at late summer flowers in pine forest openings. Comments. Our populations belong to subspecies Cercyonis oetus charon (W. H. Edwards 1872), which is the typical, dark, Rocky Mountain race.

Erebia callias W. H. Edwards, 1871 Colorado Alpine (added December 30, 2023)

Description. Among our alpines, the stippled gray underside of Colorado Alpine is unique. The forewing has a bold orange-red patch with two black eyespots. Range and Habitat. Also called the Relict Gray Alpine, this butterfly is limited to high, grassy tundra habitats in the central Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, Utah and Colorado. If it occurs in New Mexico, it will be found in that habitat in Colfax, Rio Arriba or Taos counties. Life History. Per Scott (2022), hostplants in Colorado include grasses (Poaceae): Festuca brachyphylla coloradensis, Poa fendleriana var. longiligula, P. nemoralis interior; and sedges (Cyperaceae): Kobresia myosuroides, Carex rupestris drummondiana, C. foenea. Colorado Alpine must be biennial and therefore larvae must overwinter. Flight. One summer flight is on the wing from mid-July into August. Adults visit nectar, scat and mud in tundra meadows. Dorsal basking presents fabulous photographic opportunities. On cool days, adults may feign death in low grasses or lichen-covered rocks. Comments. Colorado Alpine has not yet been found in New Mexico, but it has been found below 12,000 feet elevation only 30 miles across the border in southern Rio Grande County, Colorado. The most likely place we can think of is in the Wheeler Peak complex in the bowl just north of Old Mike Peak, where the 12,000-foot contour crosses gently sloping ground, rather than steep terrain. We still have hope!

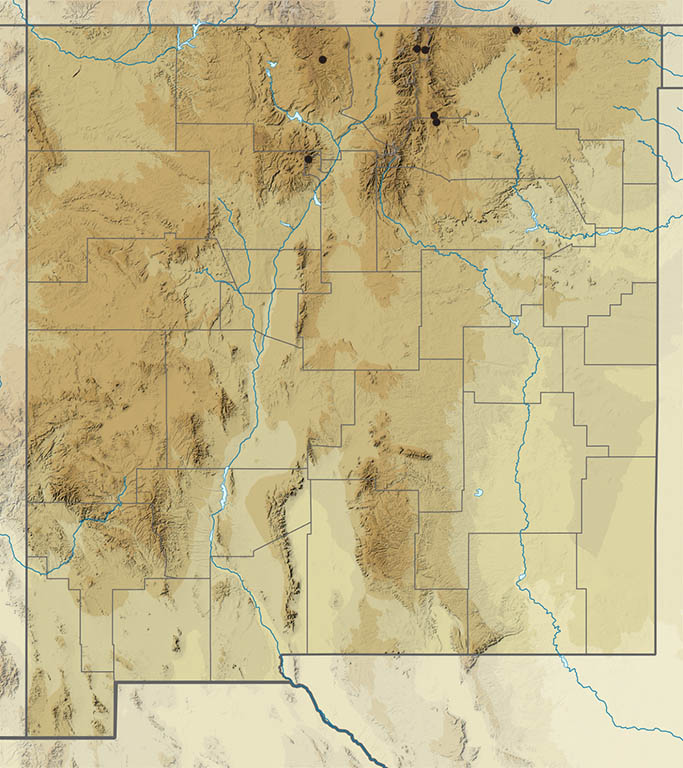

Erebia magdalena Strecker 1880 Magdalena Alpine (updated December 29, 2023)

Description. Magdalena is flat black-brown, everywhere. It is so black that it is hard to photograph; it absorbs so much light that normally exposed film just shows a void where the butterfly would be! Range and Habitat. Magdalena is a tundra insect whose colonies in the higher Rocky Mountains are relicts from Pleistocene Ice Ages. Magdalenas also in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming. In NM, they live above treeline in talus near Wheeler Pk. and State Line Pk. (counties: Ta), always above 11,500′. Life History. Scott (2022) reported that females usually place eggs on rocks, making it hard to know precisely what larvae eat. His admittedly poorly documented hostplants in Colorado include: Festuca brachyphylla coloradensis (Poaceae) is definitely a host; Carex heteroneura (Cyperaceae) is probably a host. Other grasses and sedges are quite possible, even likely. Winter is passed by larvae. Flight. A complete life cycle takes two years due to the short growing season. New Mexico adults fly between July 2 and July 24. Adults perch on boulders, nectar at a variety of flowers, and fly across scree slopes. Lateral baskers, their black wings are ideal for thermoregulation in their cold habitat. Comments. Our colonies belong to the nominate subspecies. More colonies may exist in New Mexico, but access challenges and formidable summer weather contribute to our slow learning curve for this species. Culturally speaking, Magdalena Arctic has a spiritual, mystical quality, perhaps it’s the snowy, low-oxygen, mist-shrouded high peak habitat, which Bob Pyle crystallized so well in his book Magdalena Mountain.

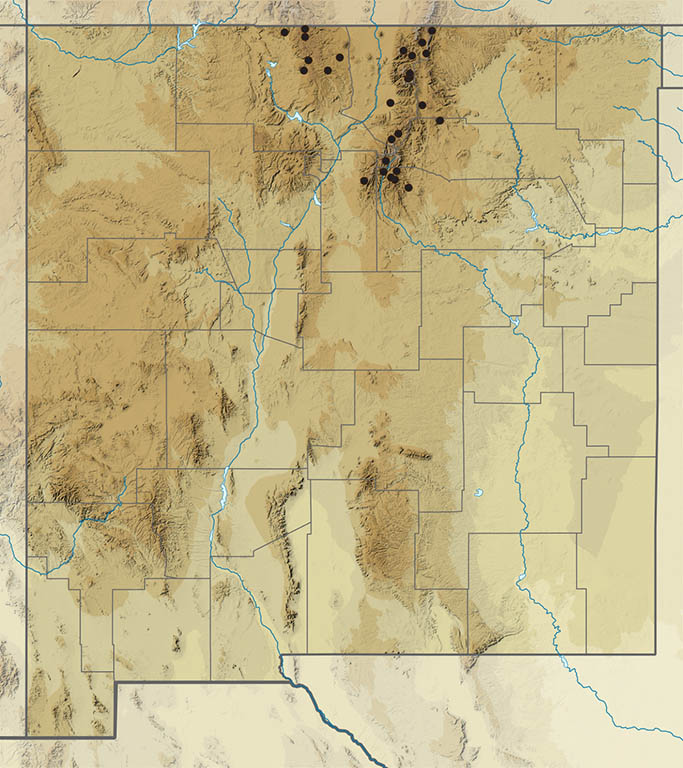

Erebia epipsodea Butler 1868 Common Alpine (updated December 30, 2023)

Description. Common Alpines are of medium size. Submarginal black eyespots are set within broad reddish patches against dark brown ground color on all wing surfaces. Range and Habitat. Erebia epipsodea lives in the western North American cordillera from Alaska south to Washington and Wyoming. Relict populations also thrive in Colorado, Utah and New Mexico. It inhabits lush (fairly tall) grassy meadows in moist valley bottoms set in the higher mountains of north-central New Mexico (counties: Co,Mo,RA,SM,SF,Ta), usually 8500 to 12,500′. Life History. Larval hosts are moist meadow grasses (Poaceae) and sedges (Cyperaceae). Scott (2022) affirms the following species as hosts, which are likely hosts in New Mexico, as well: Poa pratensis, Koeleria macrantha, Danthonia parryi, Poa fendleriana, Carex inops heliophila, Deschampsia cespitosa and Danthonia intermedia. Larvae hibernate. Flight. NM records indicate one summer flight each year, peaking in July. Extreme dates are June 6 and August 23. Adults cavort among the grasses in moist high mountain meadows, feeding at flowers and at moist earth, occasionally dorsal basking. Comments. Our colonies are considered members of the subspecies Erebia epipsodea brucei Elwes 1889, type locality “along Beaver Creek, east/northeast of Fairplay, Park County, Colorado.”

Oeneis uhleri (Reakirt 1866) Uhler’s Arctic (updated January 11, 2024)

Description. Uhler’s Arctic resembles Chryxus Arctic, but it can be separated with practice. It is smaller and whiter on the underside, which only rarely has Chryxus’ postmedian band. The forewing underside lacks the ‘bird beak’ of Oeneis chryxus. Ventral eyespots vary in development. Dorsal veins are dark on the tawny ground color. Range and Habitat. Uhler’s inhabits parts of Alaska, the Yukon and the northern Great Plains, with colonies in the central Rockies of Wyoming and Colorado. It is known from only a few New Mexico colonies, perhaps because of confusion with similar Chryxus. Here, it inhabits Transition and Canadian Zone grassy slopes (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Ta) between 8,300 and 12,700′. Life History. In southern Colorado, and probably in New Mexico, larvae prefer Festuca idahoensis (Scott 1992). Koeleria macrantha also may be used (both Poaceae). Winter is passed by larvae. Flight. Oeneis uhleri may be univoltine or biennial. Either way, adults fly in early summer. Our observations fall between May 18 and July 10. Look for them perching in grass clumps, flying low over grassy ridges, or sipping at moist soil. Comments. Our populations probably belong to the nominate race. F. M. Brown described Oeneis uhleri reinthali F. Brown 1953, from the west slope of the Rockies (near Gothic, CO) and perhaps that subspecies might characterize ours from Rio Arriba County.

Oeneis ridingsii (W. H. Edwards 1865) Ridings’ Arctic (updated July 13, 2024)

Description. Ridings’ Arctic is translucent, pale tan to gray. Submarginal bands of elongated white patches mark forewing and hindwing, above and below. The forewing has two prominent black eyespots within pale submarginal areas. Range and Habitat. Oeneis ridingsii is native to cold steppe grasslands, sagebrush and shortgrass prairies from the Sierra Nevada east to the Front Range and north to Saskatchewan. In New Mexico it likes grassy pine savannas (counties: Ca,Ci,Co,Gu,Li,MK,Mo,RA,SM,Ta,Un), 6300 to 9200′. Life History. The main host for this species in New Mexico seems to be Bouteloua gracilis, but Agropyron longifolius, Koeleria macrantha and Stipa comata also may be used (all Poaceae). Winter is passed by half-grown larvae. Flight. This butterfly is univoltine in New Mexico. Records span May 31 to July 26, but most adults are seen in June. Flying weakly and jerkily near the ground, Ridings’ males patrol grassy knolls for females. Comments. Throughout its expansive range cross the interior West, Ridings’ Arctic displays a variety of phenotypes. This may be because they live near the soil among short grasses where local populations may be prone to natural selection of individuals resembling the color of local soils and geologic materials. Many local varieties have been described as subspecies, of which New Mexico seems to have two, whose respective distributions are not well understood. Nominate Oeneis ridingsii ridingsii flies in north-central and northeast New Mexico (Co,Mo,RA,SM,Ta,Un). Oeneis ridingsii neomexicanus Austin 1986, a yellowish form which was described from Bluewater Canyon, Bluewater Lake State Park (Ci), seems to prevail in our westernmost counties (Ca,Ci,MK) and westward into the high grasslands of northern Arizona. Holland collected a solitary disjunct individual of O. ridingsii near Carrizo Peak (Li). This butterfly used to be called Neominois ridingsii.

Ridings’ Arctic (Oeneis ridingsii neomexicanus), Luna Lake, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Apache Co., AZ; June 18, 2023 (photo by Jonathan Batkin).

Oeneis melissa (Fabricius 1775) Melissa Arctic (updated December 31, 2023)

Description. On Melissa Arctic, the translucent ventral hindwing is mottled to resemble lichens, with no eyespots or (usually) banding. Uniform mottling covers the entire hindwing in females, but males have dark basal mottling and lighter distal mottling. Range and Habitat. Melissa Arctics live across arctic Canada and Alaska, south in the east to New Hampshire. Pleistocene relict colonies occupy high peaks of the central Rockies south to New Mexico. Here it lives above treeline on the barest peaks and ridges (counties: Mo,RA,SF,Ta) above 11,200′. Life History. Eggs are laid on host sedges or nearby rocks. Carex rupestris drummondiana (Cyperaceae) is used in central Colorado (Scott 1992). Larvae hibernate and take two years to mature. Flight. New Mexico records fall between June 19 and July 24, confirming a single early-summer flight. Adults fly near the ground on windy tundra ridges. When basking or perched, they blend in with lichen-covered rocks. Comments. We have Rocky Mountain subspecies Oeneis melissa lucilla W. Barnes and McDunnough 1911. Butterflying our high peaks is complicated by storms that can bring clouds, lightning, rain and hail by noon on summer days. Reaching these remote locations before noon requires planning, conditioning, and effort – a good project for energetic, young lepidopterists!

Oeneis polixenes (Fabricius 1775) Polixenes Arctic (updated December 31, 2023)

Description. Polixenes Arctic has a dark band across the median area, not unlike Chryxus Arctic. Unlike Chryxus, it has translucent wings and a greyer ground color. Range and Habitat. Polixenes Arctics have stronger polar affinities than our other Arctics. They occur from Alaska east to Baffin Island and Newfoundland, south to Maine and south in the Rockies in small pockets to Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico. They occupy very high tundra in New Mexico (counties: Mo,RA,SF,Ta), above 12,400’. They are known from Wheeler Peak, Truchas Peaks and Santa Fe Baldy. Life History. Larvae eat grasses (Poaceae) and sedges (Cyperaceae), like Carex rupestris drummondiana, Festuca brachyphylla coloradensis and Helictotrichon mortonianum. Larvae overwinter. Flight. Polixenes is biennial, but existence of even- and odd-year cohorts at a given site ensures a flight each summer. New Mexico records span June 26 to July 24. Adults patrol exposed ridges above timberline and perch in vegetation between the rocks. Comments. Rocky Mountain subspecies Oeneis polixenes brucei (W. H. Edwards 1891) occurs in our area. Oeneis polixenes was found on Santa Fe Baldy (SF) in July 1935 by Drs. Whitmer and Klots. The latter gentleman went on to author the first field guide to the butterflies of eastern North America in 1951.

Oeneis chryxus (Doubleday [1849]) Chryxus Arctic (updated January 4, 2023)

Description. Chryxus is tawny orange above with a few dark eyespots. Underneath, a pattern of white, tan and gray mimics lichen-covered rocks, usually with a dark hindwing median band. The forewing ventrum has postmedian marks resemble a bird’s head in profile, beak and all. Range and Habitat. Chryxus occupies mountains of western North America, subarctic Canada and the Great Lakes region. It is the second most widespread arctic in New Mexico (counties: Co,LA,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF,So,Ta), preferring Canadian and Hudsonian Zone meadows below treeline, 8000 to 12,700,’ sometimes creeping above treeline to mate-locate. Life History. Scott (1992) gave sedges (Cyperaceae) as the primary larval hosts in the Rockies. Of the hosts he listed for Colorado, Carex geophila and C. pennsylvanica heliophila also grow in New Mexico. Chryxus larvae overwinter. Flight. Chryxus is biennial, with two years required for larval maturation. Our records indicate flight between May 16 and July 28, mostly in June. Males establish ridgetop perches. Adults nectar, fly across alpine meadows, and are well-disguised when perched on the ground. Comments. Chryxus found below treeline in north-central New Mexico are probably typical Chryxus. Populations found above timberline in the Sangre de Cristos high country (Co,Mo,RA,SF,Ta) are probably subspecies O. c. alticordillera J. Scott 2006. Alticordillera may in fact be a distinct species, but it’s almost impossible to separate from Chryxus by appearance. Its habitats and behaviors do seem to be distinct (Andy Warren, personal communication). A disjunct, relict colony of Chryxus in the San Mateo Mountains (So) was recently described as subspecies Oeneis chryxus socorro R. Holland 2010.

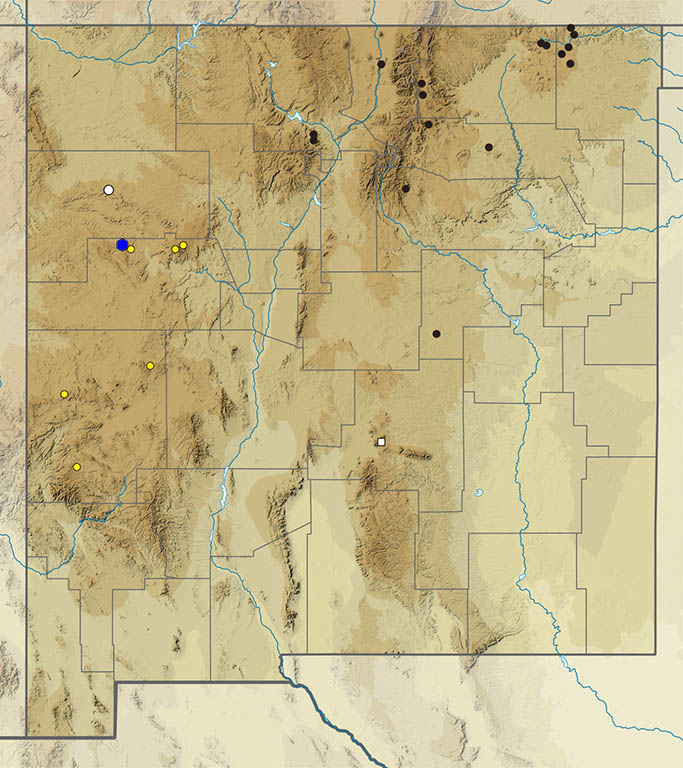

Oeneis alberta Elwes 1893 Alberta Arctic (updated January 5, 2024)

Description. Ferris and Brown (1980) accurately described this species as “reminiscent of a pale, much grayed, miniature edition of O. chryxus.” Range and Habitat. Alberta Arctics are widespread across the Canadian Plains provinces as well as adjacent Montana and North Dakota. South from there, however, only isolated and disjunct colonies occur as far as Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. Alberta inhabits windswept Canadian Zone and higher grasslands in our state (counties: Ca,Co,Un), 8200′ to 10,000’ elevation. Life History. Larvae seem to feed exclusively on bunchgrasses in the genus Festuca (Poaceae). Festuca idahoensis and Festuca arizonica are the likely hosts in northeast New Mexico. Flight. Oeneis alberta is univoltine (possibly biennial) with adults about in late spring. Our records indicate peak flight in May, shortly after snow disappears from its slow-to-warm habitat. Extreme observation dates are May 3 and June 5. Adults fly near the ground among bunchgrasses; they are not known to nectar. Comments. Grassy, windswept mesas and volcanic peaks north and east of Raton (Co,Un) are home to subspecies Oeneis alberta capulinensis F. M. Brown 1970. This rather variable race (see the three images below) was discovered on Capulin Volcano (Un) in 1969 by well-known, highly respected and much-loved Rocky Mountain lepidopterist F. Martin Brown. The colony at the type locality is now thought to be extirpated. A disjunct colony of Alberta may persist in the Mogollon Mountains (Ca); if so, it would belong to subspecies Oeneis alberta daura (Strecker 1894). Arizona’s Whites Mountains (Apache County) are a reliable place to see this critter.