by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver (updated March 15, 2022)

Sulphurs (Pieridae: Coliadinae). Our >20 species of sulphurs vary from tiny (2 cm) to large (10.2 cm) in size, with colors that range from orange through yellow, even to white. Upper surfaces have scales that reflect ultra-violet light in patterns that differ between species and between males and females within each species. Accordingly, sulphurs, like other butterflies, have vision that is finely tuned to UV wavelengths. There is a high frequency of albinism in females. Larvae of most sulphurs favor legumes (Fabaceae); a couple of species can reach pest proportions in alfalfa fields. Many of our larger sulphurs are subtropical strays that add surprise to the normal pleasures of butterflying in southern New Mexico in late summer. Photographers are routinely stymied by sulphurs because they open their wings only to fly, to warm up on cold days, or under duress. Usually, a photographer seeks out the sunlit side of a butterfly to photograph, but illumination from behind (backlighting) can reveal the upperside of a sulphur’s wings. Please let me know if you have excellent photos of sulphurs to share on this page,

- Lyside Sulphur (Kricogonia lyside)

- Dainty Sulphur (Nathalis iole)

- Barred Sulphur (Eurema daira sidonia

- Little Yellow (Pyrisitia lisa centralis; Eurema lisa

- Mimosa Yellow (Pyrisitia nise nelphe); Eurema nise

- Tailed Orange (Pyrisitia proterpia); Eurema proterpia

- Sleepy Orange (Abaeis nicippe); Eurema nicippe

- Boisduval’s Yellow (Abaeis boisduvaliana); Eurema boisduvaliana)

- Mexican Yellow (Abaeis mexicana); Eurema mexicana

- Salome Yellow (Abaeis salome jamapa); Eurema salome

- Scudder’s Sulphur (Colias scudderii ruckesi); flavotincta

- Mead’s Sulphur (Colias meadii)

- Queen Alexandra’s Sulphur (Colias alexandra); apache

- Western Clouded Sulphur (Colias eriphyle)

- formerly Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice)

- Orange Sulphur (Colias eurytheme)

- Southern Dogface (Zerene cesonia); rosa

- White Angled-Sulphur (Anteos clorinde)

- Yellow Angled-Sulphur (Anteos maerula)

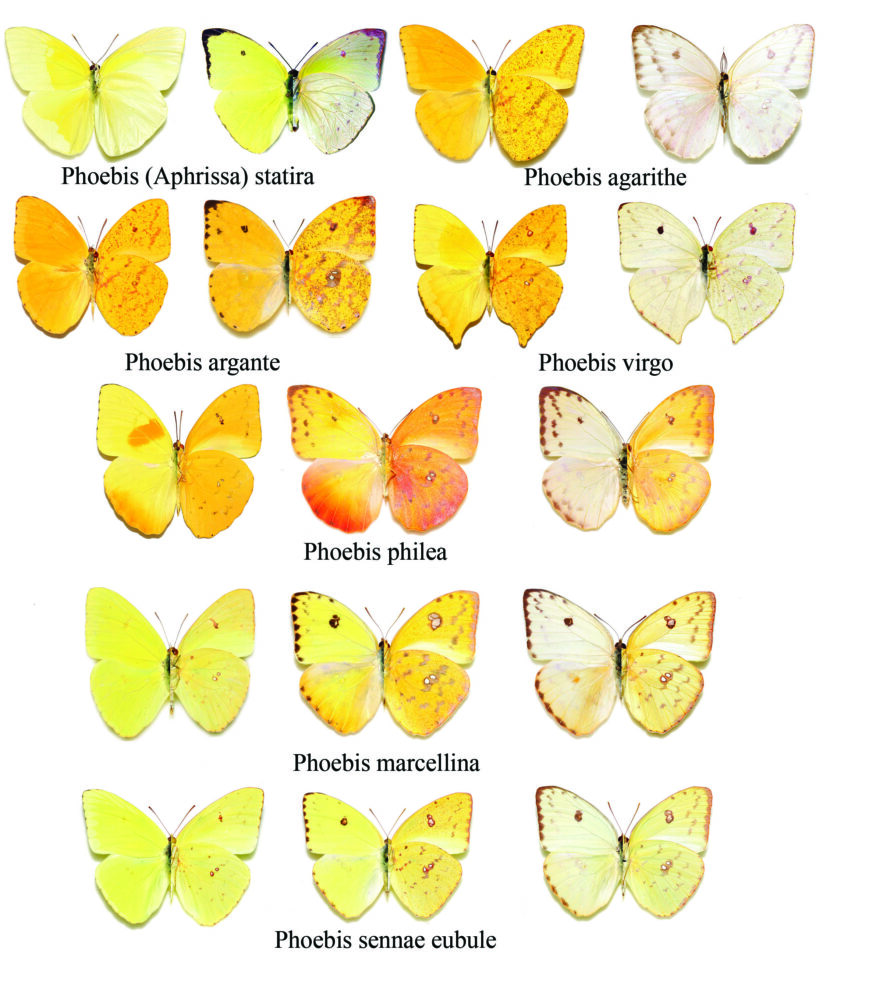

- Marcellina Sulphur (Phoebis marcellina); browni

- formerly Clouded Sulphur (Phoebis sennae)

- Eubule Sulphur (Phoebis eubule)

- formerly Clouded Sulphur (Phoebis sennae)

- Orange-Barred Sulphur (Phoebis philea)

- Large Orange Sulphur (Phoebis agarithe)

- Tailed Sulphur (Phoebis virgo); Phoebis neocypris

- Statira Sulphur (Aphrissa statira)

Kricogonia lyside (Godart, 1819) Lyside Sulphur (updated November 4, 2024)

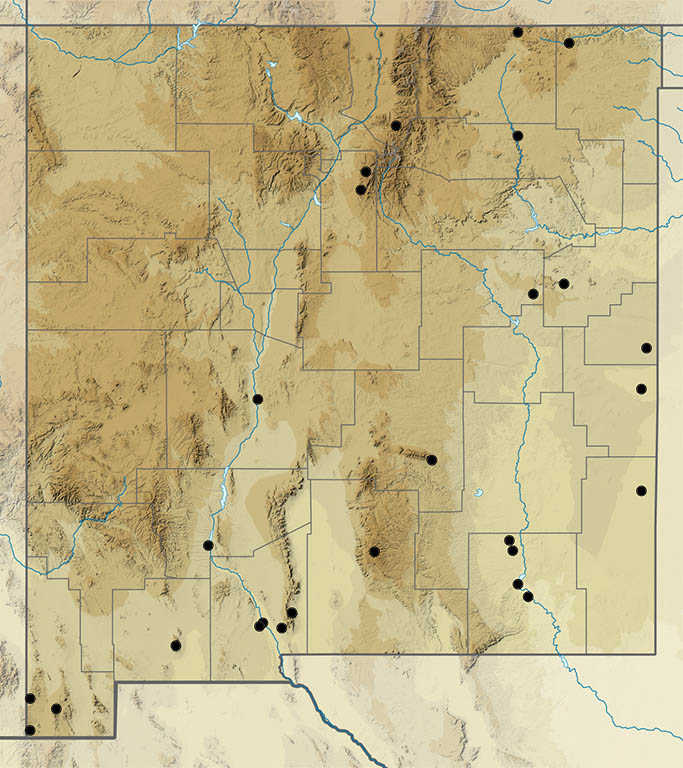

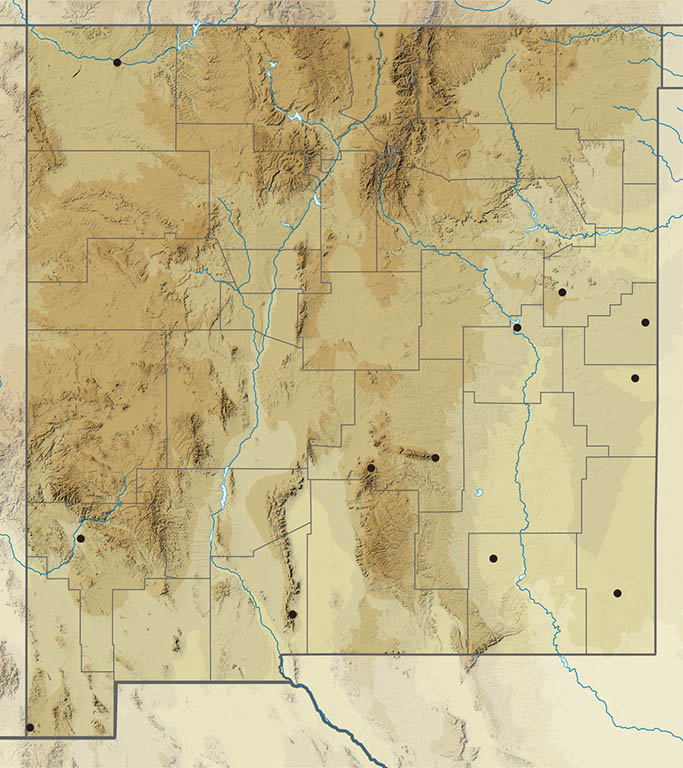

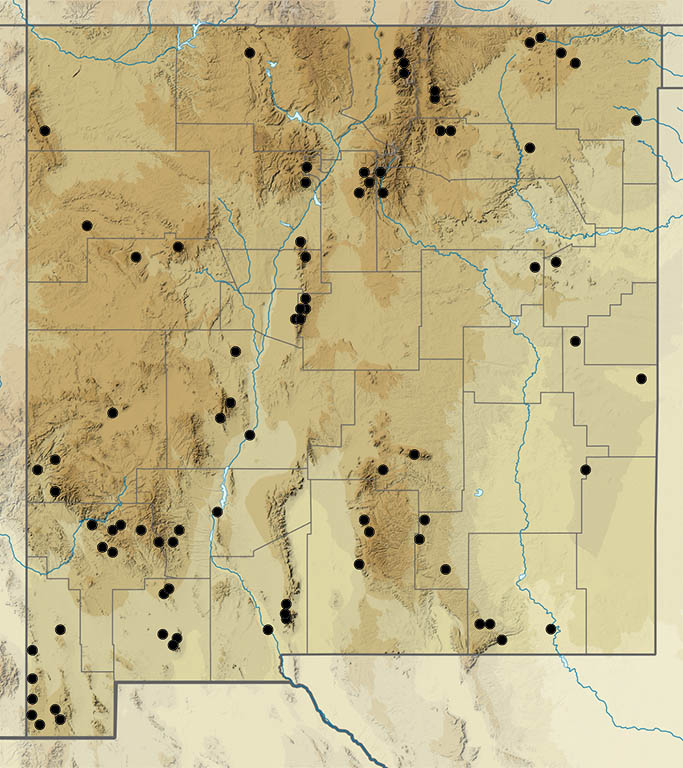

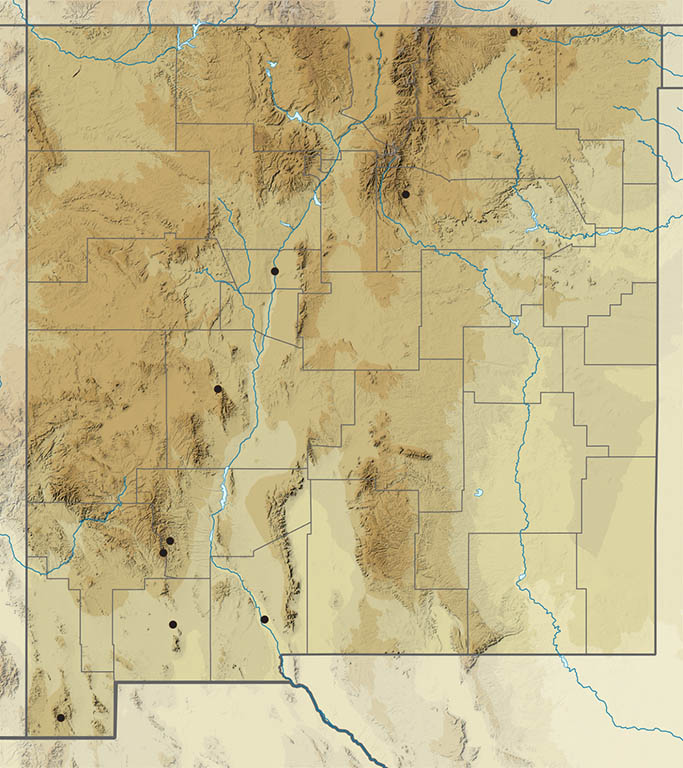

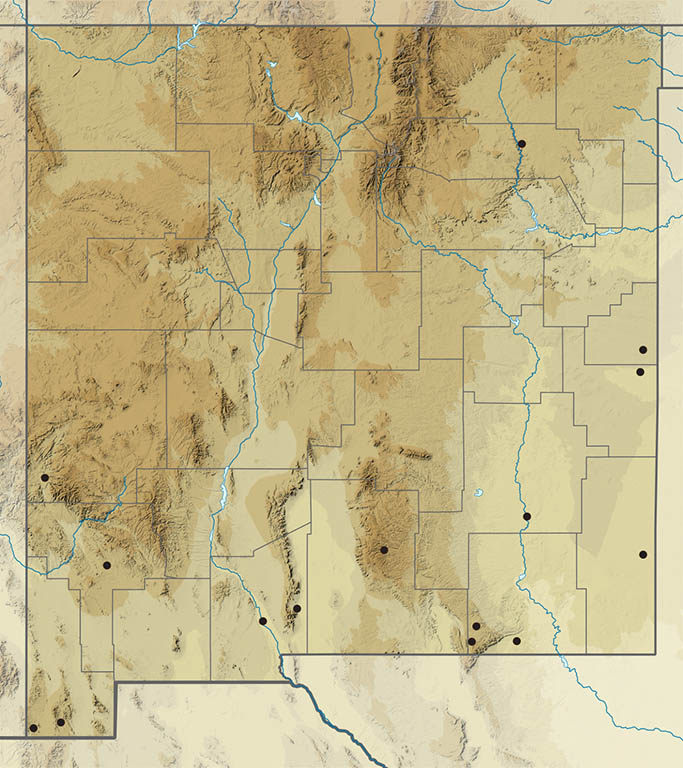

Description. Lyside is of medium size. Females are often immaculate yellow; males are usually pale with a bright yellow patch near the base of the dorsal forewing and dark marks near forewing and hindwing apices. Males have a dark curved bar near the apex of the hind wing (dorsal) which may be seen from the ventral side if the light is right. The apex of the front wind is more pointed than in most sulfurs. Range and Habitat. Lyside breeds year-round in Central America, but can wander as far north as the central Great Plains. It is a regular stray at low elevations in southern and eastern New Mexico, but irregular elsewhere (counties: Co,Cu,DB,DA,Ed,Gr,Gu,Ha,Hi,Le,Li,Lu,Ot,Qu,Ro,SF,Si,So,To,Un). Life History. Larval hosts are subtropical, woody Zygophyllaceae. There is no evidence that Kricogonia lyside breeds anywhere in New Mexico or that potential hostplants even occur in the region. Flight. This species appears to have two peaks of activity in New Mexico: a weak influx in June and a stronger one in September. All observations fall between April 22 and December 26. Lyside experiences occasional northward fluxes and may be common in good years. Comments. Adults characteristically flutter beneath low tree canopies in desert washes, fly up underneath branches and disappear by perching, wings closed, among leaves bathed in diffuse, shady green light. The earliest record of this species visiting New Mexico is from 6 miles west of Portales (Ro) on 3 June 1966 (M. E. Toliver).

Nathalis iole Boisduval 1836 Dainty Sulphur (updated March 12, 2022)

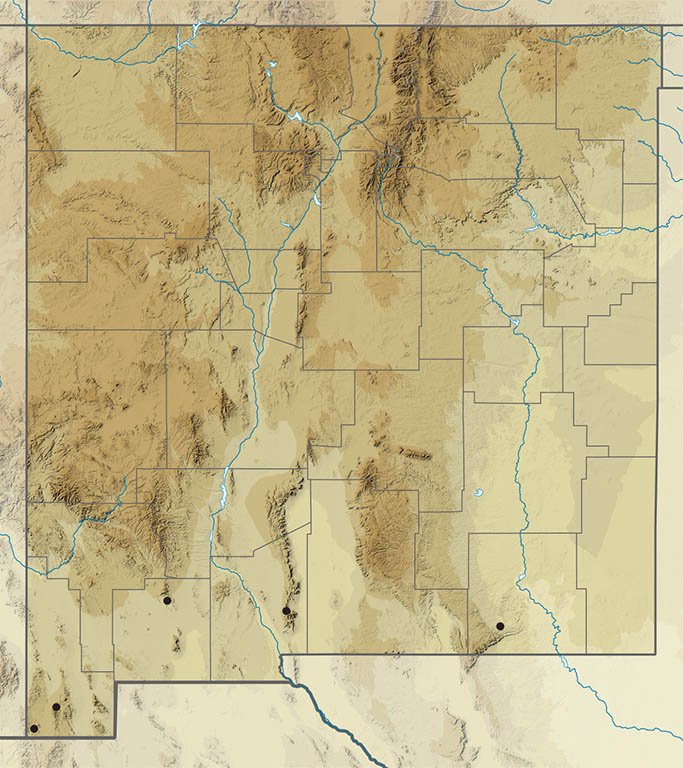

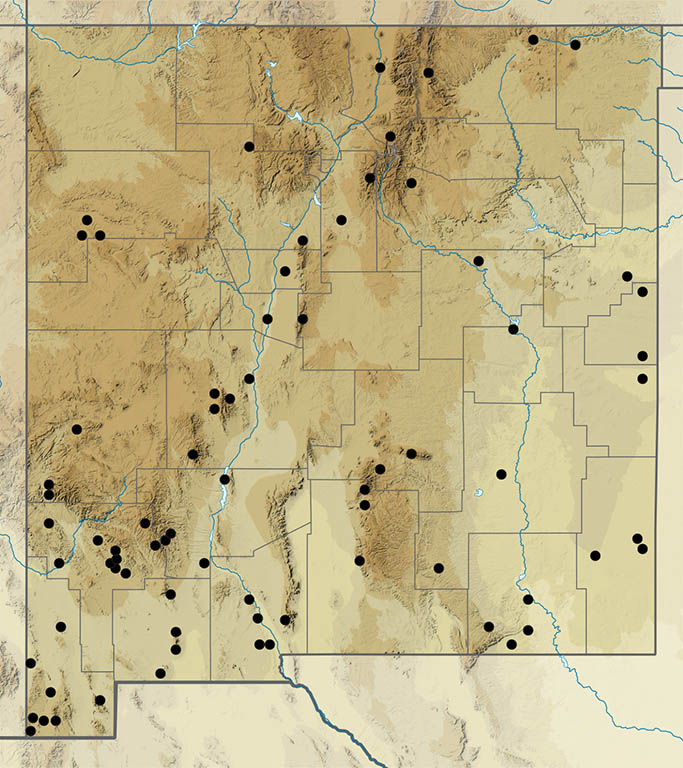

Description. This, the smallest of all North American Pierids, resembles Eurema daira, but the ventral hindwing is darker, and the dorsal hindwing has a strong black stripe at the costa. The ventral forewing has at least two prominent black spots. Males have an orange rectangular spot in the costal black stripe. Range and Habitat. Dainty Sulphur occupies disturbed places across the southern US and throughout Central America. In New Mexico it can be encountered in almost any life zone, altitude and habitat. Adults diffuse northward along roads and rivers, producing warm-season generations in most of the US. In New Mexico it is literally ubiquitous: it is known from all counties and has been found from 3000 to 12,400′ elevation. In southern New Mexico it can be in flight any time of year. Life History. Larvae use weedy Asteraceae (unusual for members of this family) including Bidens species. Scott (1992) reported oviposition on Thelesperma megapotamicum and Dyssodia papposa at Storrie Lake (SM), 23 August 1978. Flight. Nathalis iole completes several generations annually depending on length of growing season. It flies year-round on our southern border, weather permitting. Adults fly near the ground to seek nectar and moisture. Comments. Curiously, this now common and ubiquitous insect was not reported by any 19th century observer in New Mexico.

Eurema daira (Godart, 1819) Barred Yellow (updated March 12, 2022)

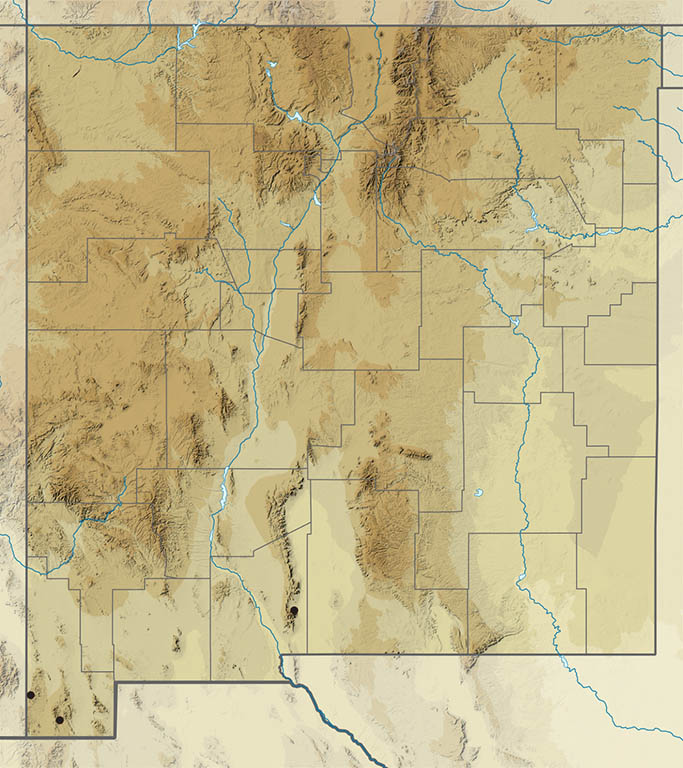

Description. All Eurema species are small, yellow or orange butterflies with some black markings. Barred Yellow is yellowish with gray margins above, with a black bar along the DFW posterior margin. It is whitish-yellow below, like Nathalis iole. Some forms have a reduced black bar on the DFW, which could lead to confusion with either Pyrisitia lisa or Pyrisitia nise. P. lisa has two small black dots at the base of the VHW and often has a round tan/pink spot at the apex of the HW. P. nise also has the pink spot and the VHW tends to be more mottled. Range and Habitat. This tropical and subtropical sulphur lives from South America north to FL and N coastal Mexico. Despite the species’ small size, it does wander, which explains its rare appearances in NM. Our one report is from Whitmire Canyon, 5400′, Peloncillo Mountains (Hi), in July 1991 (K. Roever). Life History. Various legumes (Fabaceae) are used as larval hosts in its breeding grounds, but there is no evidence of reproduction in NM. Flight. Adults fly near the ground. Strays are most likely here during or after a good summer monsoon season. Comments. Barred Yellow’s resemblance to the common, weedy Nathalis iole may cause it to be overlooked here and it may in fact be more common than we realize. Our subspecies is Eurema daira sidonia (R. Felder, 1869).

Pyrisitia lisa (Boisduval & Le Conte, 1830) Little Yellow (updated March 12, 2022)

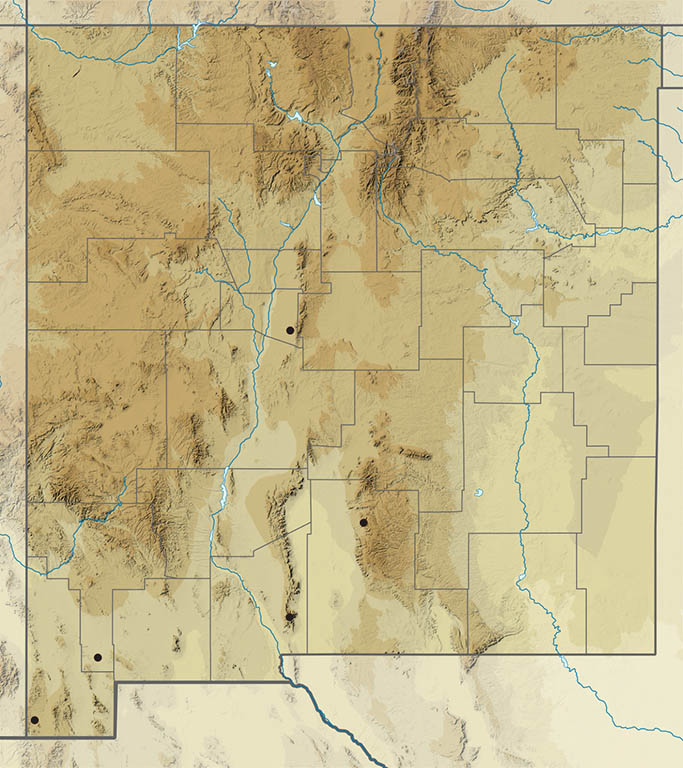

Description. Conveniently, Little Yellow is diminutive and yellow, with rounded wings. Above, the yellow is accented with black at forewing apex, along the forewing costa, and along the hindwing margin. Undersides are yellow mottled with brown squiggles and a small orange spot. Two basal black dots on the ventral hindwing costa are sufficient to distinguish Pyrisitia lisa from the very similar Pyrisitia nise and the occasional variant of Eurema daira. Range and Habitat. This species is widespread in the neotropics and eastern and central US. In New Mexico it shows up most in agricultural areas on the east side of the state (counties: Be,Cu,Ch,DA,DB,Ed,Hi,Le,Li,Qu,Ro,SJ,Sv). Life History. Nothing is known of larval hosts in New Mexico, but herbaceous legumes (Fabaceae) are used elsewhere. Pyrisitia lisa is believed to be only a seasonal resident in New Mexico because it cannot survive harsh winters. Flight. There is one report each for April and June; all other records fall between September 1 and November 1. Lack of early season reports suggests a species that is winter-killed and then is reintroduced the following year when conditions permit. Little Yellows fly close to the ground and will come to nectar. Comments. Northwest New Mexico has records dating to the 1920s (SJ,Sv), but there are no recent reports from these areas. Speculating . . . perhaps those sightings may be attributed to artificial introduction via livestock forage. This butterfly is known in some older field guides as Eurema lisa. Our subspecies is Pyrisitia lisa centralis (Herrich-Schäffer, 1865).

Pyrisitia nise (Cramer, 1775) Mimosa Yellow (updated March 12, 2022)

Description. Yellow Pyrisitia nise looks much like Pyrisitia lisa, but it is a little larger, usually lacks the black margin on the dorsal hindwing, the black scaling on the dorsal forewing costa and the two basal black dots on the ventral forewing costa and the black spot at the end of the cell on the dorsal forewing. Range and Habitat. Mimosa Yellows occur along our southern border, but only rarely (counties: DA,Ed,Hi,Lu). They breed routinely in the Neotropics and subtropics, sometimes wandering north as far as New Mexico. Occasional fresh specimens imply that seasonal reproduction does occur in the Southwest. This species is multivoltine farther south. Life History. Larvae eat legumes (Fabaceae). Bailowitz and Brock (2021) suggested larvae use Acacia constricta in Sonora, MX. Scott (1986) indicated larvae eat species of Cassia and Lysiloma. This butterfly might produce a local summer flight in rare years like 2021, but it cannot survive our winters. Flight. Our handful of Mimosa Yellow sightings fall in June, July, September, October and November. Adults are found in low, wooded riparian situations below 6000’ elevation where they seek damp soil and nectar. Comments. Strays to New Mexico belong to subspecies Pyrisitia nise nelphe (R. Felder 1869). In some books this butterfly is known as Eurema nise.

Pyrisitia proterpia (Fabricius, 1775) Tailed Orange (updated September 7, 2022)

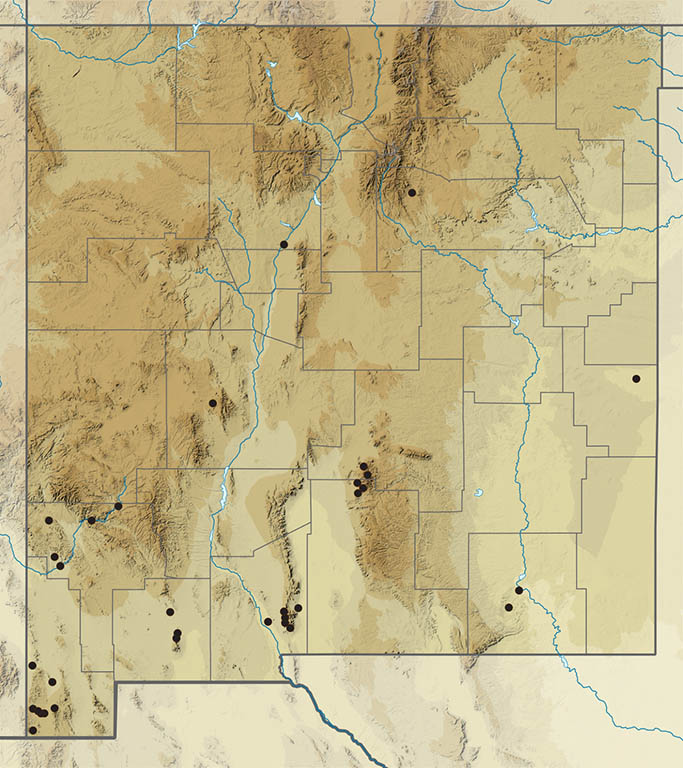

Description. Tailed Orange comes in cool season and warm season forms. The summer form is radiant yellow-orange above. A black stripe accentuates the dorsal forewing costa, and dorsal veins are delicately penciled in black. The ventral surface is matte yellow with a few faint brown smudges. The summer form has a noticeable angle at the hindwing tornus. Winter form gundlachia sports a prominent tail and more persuasive dead-leaf markings ventrally. Uppersides have black forewing apexes and no black vein-edging. Range and Habitat. This is a tropical and subtropical species distributed mostly in Central America, but it does breed northward along the Mexican coasts. Adults often wander farther north into the southwest US, where summer breeding takes place on a regular basis. In NM it is found mostly in our SW corner (counties: DA,Gr,Hi,Lu), infrequently straying north and east from there (Ca,Ed,Li,Ot,Ro,Sv,SM?,Si,So). Life History. Legumes (Fabaceae) serve as larval hosts for this insect. Scott (1986) listed Prosopis reptans and Cassia texana for Texas. Bailowitz and Brock (2021) cited Chamaecrista nictitans var. leptadenia in southeast AZ. Scott (1992) reported oviposition on honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) in southern Arizona and it would be an easy, widespread choice in southern New Mexico. Flight. In New Mexico, peak numbers in August and September probably result from successful reproduction by early-season strays followed by a wet monsoon season. Extreme dates are July 4 and November 29. In late summer and fall, look for Tailed Oranges at wet spots in riparian canyons in southern New Mexico, where they hang out with Sleepy Oranges and Mexican Yellows. Comments. The earliest known New Mexico record is a specimen at the Allyn Museum of Entomology from Redrock (Gr), collected on 8 October 1937. Some workers place this butterfly in the genus Eurema. In the breakout year of 2021, this butterfly was seen for the first time in Catron, Lincoln and Luna counties.

Abaeis nicippe (Cramer, 1779) Sleepy Orange (updated March 26, 2022)

Description. Sleepy Orange has bright orange yellow uppersides with irregular black borders on both wings and a black spot in the forewing cell. Dorsally, males have a strong UV reflectance which females lack. The dorsal hindwing border is weak in females. Undersides display a mottled, dead-leaf yellow and brown. Range and Habitat. Abaeis nicippe breeds from South America to the southern US, straying rarely to Canada. A regular member of our southern butterfly fauna, adults occasionally wander across the rest of New Mexico (all counties). Life History. Legumes (Fabaceae) are the preferred hosts. Females oviposited on twinleaf senna (Senna bauhinoides) near Santa Rosa (Gu) on May 30, 2003, and near Las Cruces (DA) on March 24, 2022 (J. Von Loh). Bailowitz and Brock (2021) cited use of Senna hirsuta v.leptocarpa, S. wislizenii, S. covesii and S. lindheimeriana in southeast Arizona. Larvae eat leaves and flowers. Flight. Sleepy Oranges can fly any time of year on warm days in southern New Mexico, where records span January 1 to December 30, but their population usually surges from summer through autumn. Adults puddle at water holes on hot days and can hibernate, which is unusual among sulfurs. Comments. One day on a roadside near Deming, crab spiders hidden in purple thistle flowers had killed a male Sleepy Orange and, 100 feet away, a female Sleepy Orange. Each victim’s wings were appressed (open) in death. The UV-reflective male died alone, but six males frenetically courted the non-reflective, but unresponsive female. This species is called Eurema nicippe in older field guides.

Abaeis boisduvaliana C. and R. Felder 1865 Boisduval’s Yellow (updated March 11, 2022)

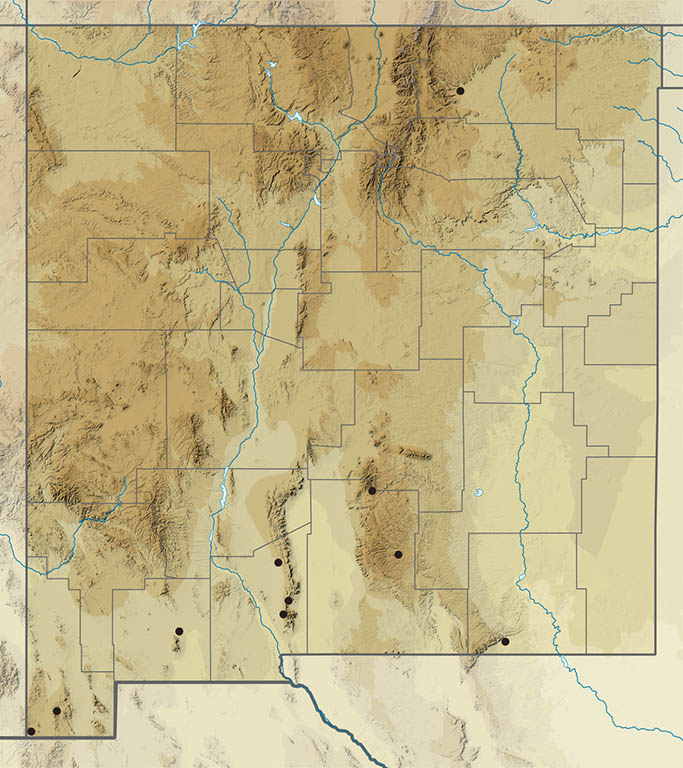

Description. This sulphur is yellow above with black margins and a slight tail at the back of the hindwing. The irregular, but consistent, black margin runs from forewing apex to hindwing tornus on males. On females, the black is limited to the forewing apex and on the hindwing does reach the tornus. The warm season form is bright yellow, while the cool season morph has more brown marks on the underside, to resemble fallen autumn leaves. Boisduval’s looks much like Mexican Yellow, but the dorsal yellow is much brighter in this species and the “dog face” silhouette in the forewing black border is much more smoothed and less evident. Range and Habitat. Abaeis boisduvaliana breeds in Central America, the Caribbean islands and north along both coasts of Mexico. Strays occasionally wander into New Mexico, mostly along our southern border, but rarely farther north (counties: Co[!],DA,Ed,Hi,Lu,Ot). Life History. Bailowitz and Brock (2021) reported larval use of Senna hirsuta v. leptocarpa (Fabaceae) in southeast Arizona. Occasional appearance of fresh individuals indicates that seasonal breeding does occur in New Mexico, but none will survive winter. Flight. Boisduval’s Yellow is multivoltine in the tropics. We have two flight peaks here: in June and September. Extreme dates are May 16 and October 17. Adults are never expected here, but are most frequently encountered in low elevation, moist, wooded riparian settings. Comments. Some authorities treat this butterfly as a subspecies of Abaeis arbela (Geyer). Our first report was from the legendary Guadalupe Canyon, 4600′, Peloncillo Mountains (Hi), on 8 September 1984 (S. Cary). Most older field guides use Eurema as the genus. The cool season version of this butterfly so closely resembles Mexican Yellow that it may be overlooked and thus be less rare than we think.

Abaeis mexicana (Boisduval, 1836) Mexican Yellow (updated March 11, 2022)

Description. Mexican Yellow is about the same size as Sleepy Orange, but is pale yellow above, with a distinctive black margin showing a pronounced “dog face.” The dorsal hindwing is bright yellow near the costa. There is a rudimentary tail at the hindwing tornus and a distinctive small, black patch near the hindwing apex. Range and Habitat. Abaeis mexicana breeds from Colombia north through Mexico and into southern Texas, Arizona and New Mexico. Adults stray from time to time into much of New Mexico (all counties except Cu,DB). Wanderers may breed during the warm season in northern New Mexico, far north of their core range. Usually found below 7000′, Mexican Yellow has been seen on Bull-of-the-Woods Mountain at 12,700’ (Ta)! Life History. Larval hosts are legumes (Fabaceae). Scott (1986) mentioned Cassia, Acacia and Robinia neomexicana, while Bailowitz and Brock (2021) noted exclusive use of Acacia angustissima by larvae in southeast Arizona. Flight. Our records begin January 1 and go to December 27, so it can be year-round in the south if weather cooperates. Peak flight tends to coincide with the summer monsoon: July to September. Adults are fond of nectar and wet sand in desert canyons. Comments. This butterfly was dubbed the “Wolf-Face Sulphur” by Scott (1986) because the black dorsal forewing margin has such a lobo-like profile.

Abaeis salome (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1861) Salome Yellow (updated March 11, 2022)

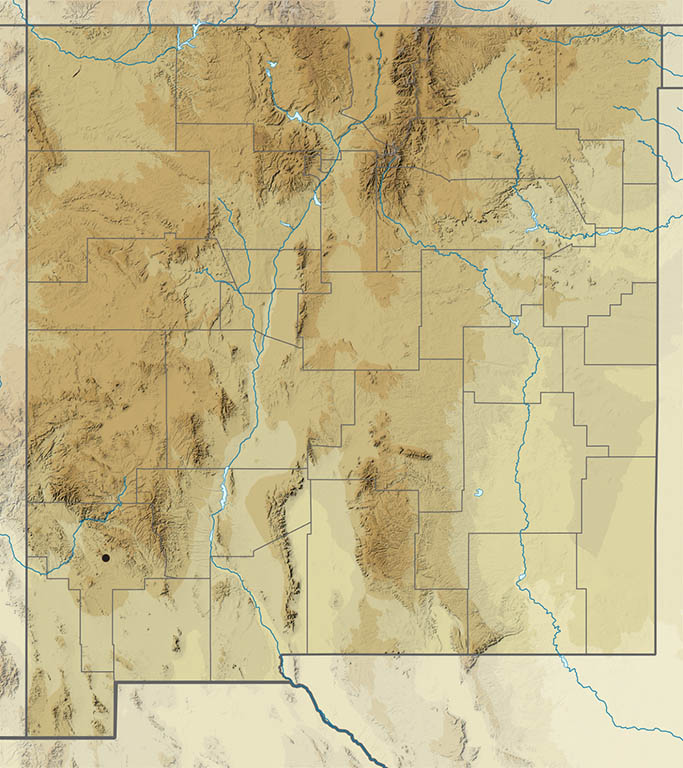

Description. This subtropical sulphur resembles its close relatives. It is a very rare late summer stray to the US and southwestern New Mexico. Range and Habitat. The Salome Yellow is a native of he Neotropics, from Peru north to Mexico, rarely straying north into Texas and New Mexico. Life history. Larvae feed on Fabaceae; Diphysa is a recorded host in its native range. No plants of that genus occur in New Mexico. Flight. The species flies all year in its native habitats, where it prefers forest edges. Comments. Salome was first officially attributed to New Mexico in “How to Know the Butterflies” by Paul and Anne Ehrlich (1961), but without substantiating data. As a consequence, it was only with qualifications included in subsequent New Mexico lists and summaries (e.g., Cary and Holland 1992[1994], Toliver et al. 2001). The specimen illustrated by the Ehrlichs was eventually uncovered in the Snow Entomological Museum at the University of Kansas bearing the labels “New Mexico” and “August” (Cary and Holland 2002). The museum and those labels are consistent with capture by University of Kansas Professor Francis Huntington Snow during August 1884 in Little Walnut Canyon in north of Silver City (Grant County). Our subspecies is Abaeis salome jamapa (Reakirt, 1866).

Colias scudderii Reakirt, 1865 Scudder’s Sulphur (updated March 11, 2022)

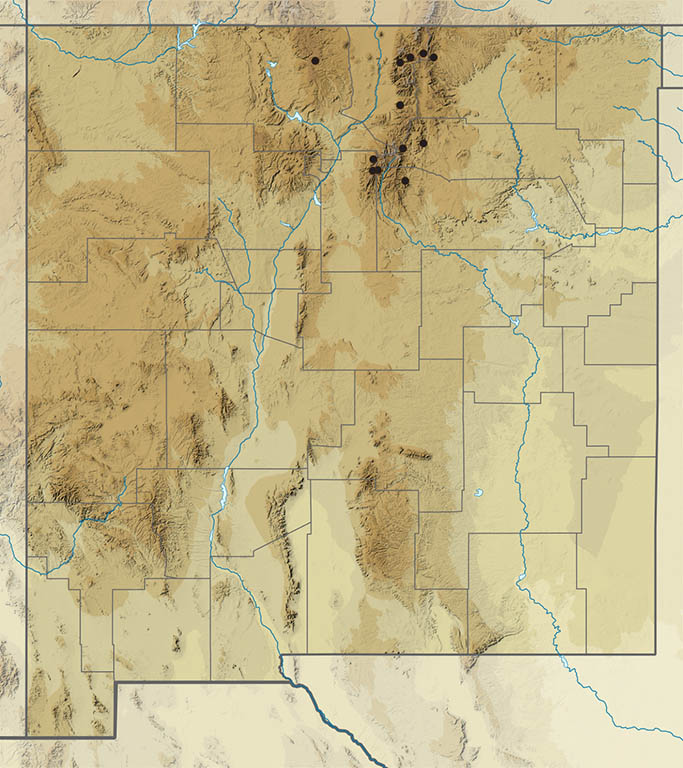

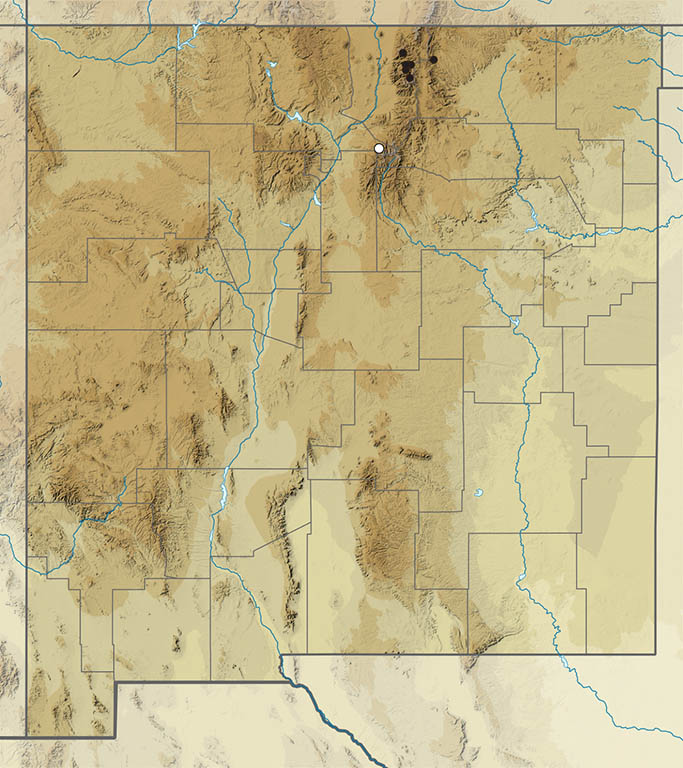

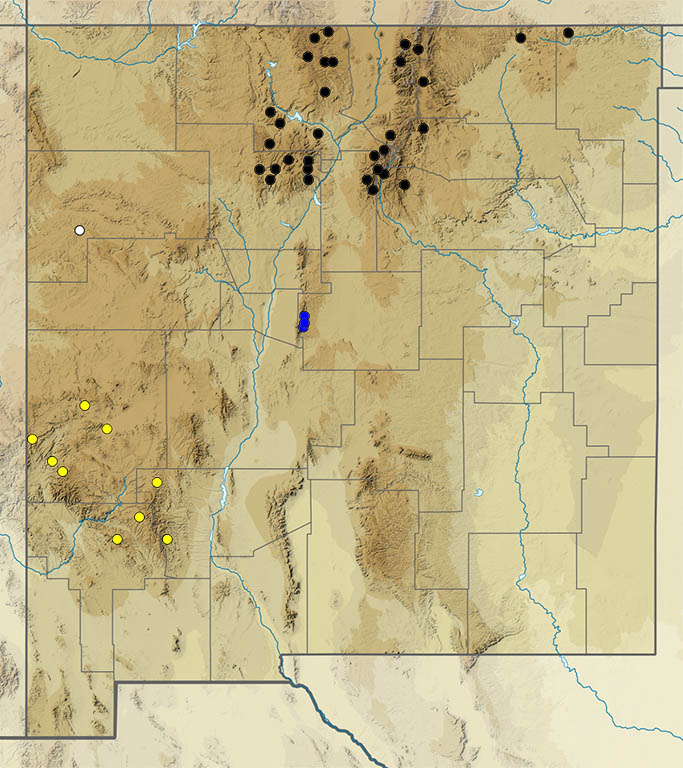

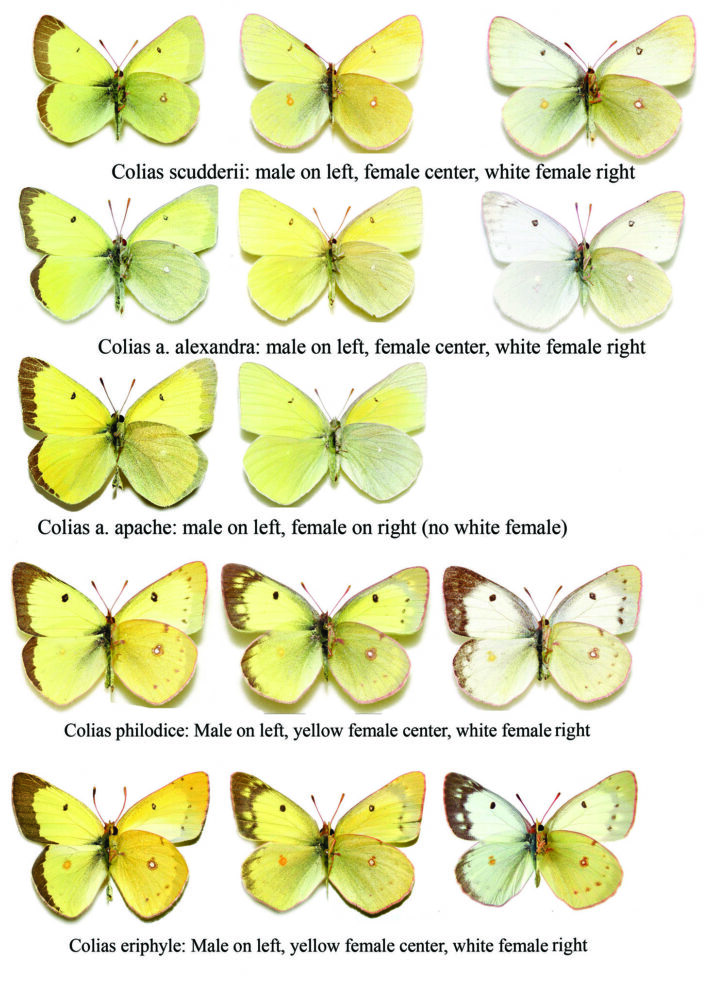

Description. Scudder’s Sulphur resembles Clouded Sulphur, the widespread agricultural weed, but life history details and habitat distinguish them. Scudder’s has pink fringes and a greenish ventrum. Females are pale yellow-green above with ghosts of dark borders unlike females of Clouded Sulphur. Scudder’s also lacks the VHW submarginal dark spots typical of Clouded Sulphur. Range and Habitat. Colias scudderii lives in the central Rocky Mountains, from Wyoming and Utah south into extreme northern New Mexico (counties: Co,Mo,RA,SM,SF,Ta). Look for it in damp areas near treeline, from 9,000 to 12,400′. Life History. Scrubby willows (Salicaceae) are preferred hosts. For Colias scudderii in Colorado, oviposition on Salix planifolia, Salix reticulata nivalis and Vaccinium spp. (blueberries) has been reported (Scott 1992; Fisher 2012). Flight. Adult Scudder’s Sulphurs fly in New Mexico between July 1 and August 27. They are best found in high wet meadows near stands of the larval host. Comments. New Mexico populations are assigned by some (e.g., Ferris and Brown 1980) to subspecies Colias scudderii ruckesi Klots 1937, a taxon described from specimens collected in Winsor Canyon west of Cowles (SM or SF) on 2 July 1935 and 4 July 1936. That name takes a back seat to Colias scudderii flavotincta Cockerell 1901, which was described from the same general area much earlier (Cockerell 1901); note – the type locality was incorrectly changed to Colorado by Ferris [1987]). Notwithstanding those New Mexico-specific options, most recent workers do not think the variation within C. scudderii merits subdivision into subspecies.

Colias meadii W. H. Edwards, 1871 Mead’s Sulphur (updated March 11, 2022)

Description. Dorsally, Mead’s Sulphur is almost pumpkin orange. Its distinctively pink-edged, greenish-gray underside provides excellent camouflage in its moist tundra habitat. Females are darker gray below than are males, and darker orange above with orange spots invading the marginal dark edge on the DFW. Albinic females, which are routine in many sulphur species, are quite unusual for Mead’s Sulphur. Range and Habitat. This arctic/alpine butterfly lives in scattered populations in the higher Rockies from British Columbia south to north-central New Mexico (counties: Co,RA?,Ta). In our state it occupies the highest meadows between treeline and talus. While it has been found as low as 10,000′ elevation as well as on tundra ridges, it is most often found above 11,500′ in moist meadows. Life History. Clovers (Fabaceae) such as Trifolium dasyphyllum, T. nanum and T. parryi are eaten by caterpillars in Colorado (Scott 1992) and probably here, too. Colias meadii is biennial; two warm seasons are needed before larvae pupate. Flight. New Mexico records span June 30 to August 30, peaking in July. Adults come to nectar. When disturbed or when clouds cover the sun, adults fly to the ground and disappear among the low, green vegetation. Comments. Richard Holland was the first to document Colias meadii in New Mexico: 2 miles east of Twining, 10,000′ (Ta) on 30 August 1964, during his first year in New Mexico.

Colias alexandra W. H. Edwards, 1863 Queen Alexandra’s Sulphur (updated August 5, 2022)

Description. This elegant species is our largest member of the genus Colias. It is pale gray-green below and lemon yellow above. Narrow black dorsal borders above are dark in males and weak or absent in females. Range and Habitat. Queen Alexandra’s Sulphur is a species of the western North American cordillera. It occurs from Alaska south to Arizona and New Mexico, and from the Sierra Nevada eastward into the western Great Plains. It lives in Transition and Canadian Zone forests in our higher mountains (counties: Ca,Co,Gr,LA,MK?,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF,Si,Ta,To,Un), usually 7,000 – 11,000′ elevation. Life History. Herbaceous legumes (Fabaceae) are hosts throughout its range. Larval hosts in New Mexico include Thermopsis spp. (e.g., T. divaricarpa) and Astragalus spp. (e.g., A. adsurgens). Larvae overwinter. Flight. Colias alexandra is univoltine with adults in flight here between May 19 and August 20; peak numbers are seen in July. Adults nectar in alpine meadows but are difficult to approach. Comments. Southwestern New Mexico (counties: Ca,Gr,Si) has subspecies Colias alexandra apache Ferris 1988. The Manzano Mountains population (To) should be investigated to find out if it truly belongs with apache or with nominate alexandra, which prevails to the north. The McKinley County report is a century-old John Woodgate specimen with a Fort Wingate label. Given what we know about other specimens with that provenance, a McKinley County origin cannot be assumed. Confirmation is needed.

Colias eriphyle W. H. Edwards, 1876 Western Clouded Sulphur (updated March 19, 2023)

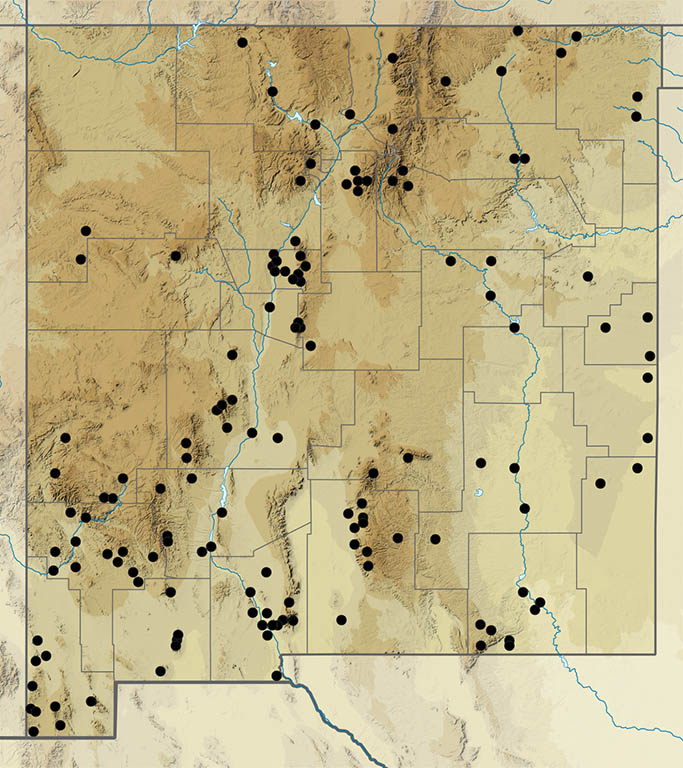

Description. The Western Clouded Sulfur is yellow with black dorsal borders and of medium size. Ventral wing surfaces may be grayish to greenish yellow for camouflage, but the dorsal surface is bright, sulfurous yellow. In females, the dorsal black border is invaded by yellow patches, as it is with other Colias species. Males do not reflect ultraviolet light, but females do. Albinic females, having a very pale green-white hue, occur regularly. The VHW usually has a series of submarginal dark spots, and the VHW central spot is often doubled. Range and Habitat. Colias eriphyle occurs across most of western North America, where it inhabits disturbed, open, often agricultural areas. It is known throughout New Mexico (all counties), where its altitudinal range is 3000 – 10,000′. Life History. A variety of weedy legumes (Fabaceae), such as alfalfa (Medicago sativa), serve as larval hosts. Extensive monocultures of some hosts may lead to locally abundant Western Clouded Sulphurs. Thousands were seen on 9 October 1994 near Dexter (Ch) by S. Cary. Flight. Adults feed on flower nectar (e.g., Aster). Several generations are completed annually in favorable areas. Reproduction begins in spring and numbers increase arithmetically until cold autumn/winter weather shuts it all down. Our official records extend from March 24 through December 29, but adults may be found in any month when the weather is warm, especially in agricultural areas. Comments. A specimen taken at NMSU, Las Cruces (DA) on June 1961 represents New Mexico’s oldest known record, despite the 1890s presence of energetic field entomologists T. D. A. Cockerell and C. H. T. Townsend who staffed the precursor of New Mexico State University. Western Clouded Sulphur (Colias eriphyle) was recently distinguished from its eastern counterpart, Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice), which is what we used to call ours. Andy Warren suggests the interface between C. eriphyle and C. philodice lies between eastern Nebraska-Kansas-Oklahoma and western Iowa-Missouri-Arkansas. One wonders what eriphyle and philodice do when they encounter each other . . .

Colias eurytheme Boisduval, 1852 Orange Sulphur (updated October 19, 2023)

Description. Clouded Sulphur has identical size and shape, but Orange Sulphur has a powdery orange-yellow dorsal ground color and males reflect ultraviolet light. The amount of orange varies considerably, often seasonally (early and late season individuals may have small amounts of orange, though they often have dark over-scaling which Colias philodice lacks). If there is any orange at all, your specimen is likely eurytheme, or at least a hybrid. The centrally located silvery spot on the VHW is single in this species, but often double in philodice. Albinic females occur routinely and are virtually impossible to separate into Clouded vs. Orange. Range and Habitat. Colias eurytheme occurs throughout temperate North America and Mexico. It is a common and widespread butterfly in New Mexico (all counties) which is now at home in habitats from desert to tundra. Life History. Orange Sulphurs breed successfully on native, exotic and agricultural leguminous (Fabaceae) hosts. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) is a common weed and crop in New Mexico, hence abundant Orange Sulphurs. Oviposition also has been reported in New Mexico on Medicago lupulina and Vicia exigua (Scott 1992). Eggs were laid on Vicia americana on Glorieta Baldy (SF) on 12 July 1997. Flight. Colias eurytheme completes as many generations in a year as conditions allow. New Mexico records span January 3 to December 26, indicating it can be found any time of year if weather permits. Adults come to nectar and may congregate in numbers at mud puddles. Comments. Colias philodice and Colias eurytheme are very closely related, sharing hosts and mate-locating behaviors. Different UV reflectances deter interspecific mating, but hybridization still occurs and some offspring are fertile. Hybrids have some orange scales and intermediate UV reflectance. Unlike Colias eriphyle, Colias eurytheme was already part of the western butterfly fauna in the 1870s (Mead 1875).

Zerene cesonia (Stoll, 1790) Southern Dogface (updated March 12, 2022)

Description. Southern Dogface is easily recognized by its bright yellow color and black dorsal forewing margin that forms a silhouette of the head of a dog, which even has a black circle for an eye. The forewing is pointed or gently hooked. The dark DFW border in females is invaded by yellow spots, often obscuring the “dog face”. Range and Habitat. Southern Dogface is native to the American tropics and subtropics, breeding from Argentina to the southern US. It strays widely and has been recorded as far north as Canada. In New Mexico it has been reported from almost all counties (except SJ), but it is common only along our southern border and below 7000 feet elevation; it is a semi-routine summer stray farther north. Life History. A variety of legumes (Fabaceae) are larval host plants. Fresh specimens can be found throughout the warm season across southern New Mexico, suggesting at least seasonal reproduction. Flight. New Mexico records span January 7 to December 24, indicating multiple overlapping generations and virtually continuous flight along our southern border, weather permitting. Adults are found on most warm season days in southern New Mexico, but only May to August in northern New Mexico. Adults are avid nectar feeders (e.g., Asclepias species) and are popular at puddle parties. Comments. Spring and autumn individuals may have wing edges colorfully accentuated with pink (form rosa). And in case you were wondering, there is no ‘Northern Dogface’.

Anteos clorinde (Godart [1824]) White Angled-Sulphur (updated March 14, 2022)

Description. Our two Angled-Sulphurs (Anteos species) are our largest pierids. Anteos clorinde is whitish above with orange patches at the forewing costa. Ventral colors are pale greenish and vaguely leaflike. The forewing apex is hooked and the hindwing has a short tail. The wing margin’s various swoops, angles, points and corners give rise to its common name. Range and Habitat. White Angled-Sulphurs breed in the Neotropics, perhaps as far north as western Mexico. Here in New Mexico it is encountered only as an infrequent stray (counties: Be,Co,Gr,Hi,Lu,Ot,SM,Si,So). Life History. Larval hosts are shrubby legumes (Fabaceae) such as various Cassia species. There is no convincing evidence that this butterfly reproduces anywhere in the US. Flight. Adults fly fast, high and erratically, posing challenges for capture, photography or identification. Your best chance for any of those goals is when they stop to nectar, often bending flower heads with their weight. The superb photos below are prime examples of being prepared and seizing that moment. There are sight reports for July, but substantiated records run from August 8 to October 26. Comments. Our first and most surprising record came from J. R. Merritt, who caught one at Yankee, 5 miles east of Raton (Co), on 1 September 1934.

Anteos maerula (Fabricius, 1775) Yellow Angled-Sulphur (updated March 14, 2022)

Description. Anteos maerula is the yellow sister species to Anteos clorinde. It is otherwise nearly identical, lacking only the bright orange dorsal forewing patch. Like its congener, each of the four wings has a single dark cell spot. Range and Habitat. Yellow Angled-Sulphur is neotropical, but strays occasionally do reach the US. In New Mexico it is quite rare (counties: DA,Hi). Life History. Woody legumes (Fabaceae) are larval hosts in its Neotropical breeding grounds, but there is no evidence of reproduction in the US. New Mexico records are few, running from July 20 to November 3, synchronous with and following our usual summer thunderstorm season and probably capitalizing on its southerly flow of air. Flight. Adults may be more common here than reports suggest, but their high, rapid flight and resemblance (when in rapid flight) to other large sulphurs makes them difficult to identify confidently from a distance.

Phoebis marcellina (Cramer 1777) Marcellina Sulphur (updated August 14, 2024)

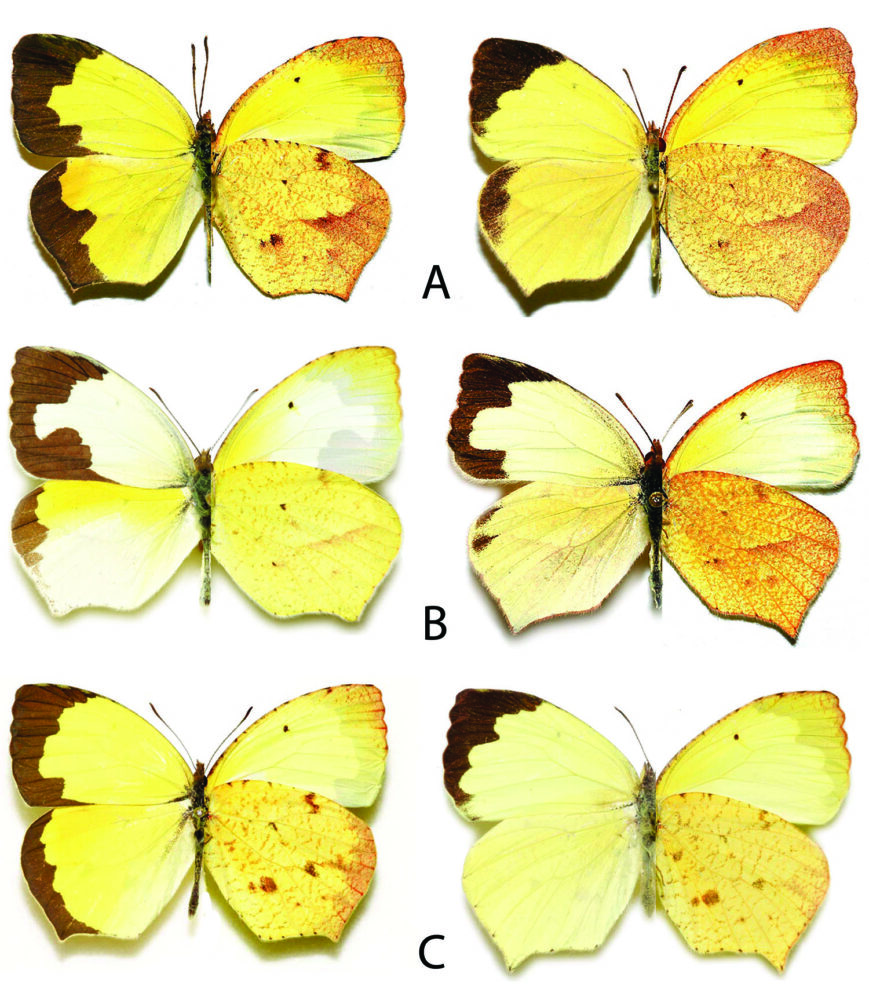

Description. Marcellina Sulphur is larger than most sulphurs, but not as large as the Angled-Sulphurs. Males are largely unmarked on the upperside, whereas females have small dark marks along the wing margins. Forewing apices are rounded, not hooked. Wing fringes are pink on cool season forms, while those of Orange-Barred Sulphur are orange. Large Orange Sulfur is similar in size and habits, but it is aptly named, males being apricot orange above and below instead of yellow. Female Large Orange Sulphurs can be confusing as their color ranges from orange to white. A distinguishing character is the line running from the forewing apex towards the back edge; this line is broken in Marcellina but straight and unbroken in Large Orange. Range and Habitat. Marcellina Sulphur is a tropical and subtropical species that breeds in South America, Central America and Mexico including the southwestern border of the US. Its large size, several annual broods and confident, wandering flight make it a routine stray farther north. In New Mexico it is regular in the south, breeding at least seasonally, though it may be scarce for years at a time (all counties but Ci,Ha,Mo,RA,SJ). Life History. Shrubby legumes (Fabaceae) are hosts. According to Bailowitz and Brock (2021), larvae are known to eat several Senna spp. as well as Chamaecrista nictitans var. leptadenia (all Fabaceae). Come summer, Phoebis marcellina breeds in New Mexico, too, using at least Senna species in Socorro County (J. Schelling & R. Gracey 2018). Flight. New Mexico records extend from March 22 to December 7. Peak numbers are in April and August, suggesting at least two annual broods in our region. Adults are fond of wet sand and flower nectar. Comment 1. We used to call this beauty the Cloudless Sulphur (Phoebis sennae). However, recent DNA studies (Nunez et al. 2019) indicate that “Cloudless” is a complex of very similar sulphurs that span South America to North America and stretch from coast to coast. Marcellina is Mexican and western, while Eubule is southeastern US. Strays of P. eubule from the Gulf of Mexico may not be surprising in eastern New Mexico. Comment 2. Albinic white females (form browni) sometimes outnumber the yellow version. Comment 3. The first photo below was taken by Bob Barber, a superb naturalist and photographer who lived in Alamogordo and, sadly, is no longer with us.

Phoebis eubule (Linnaeus, 1767) Eubule Sulphur (added May 12, 2024)

Description. Eubule Sulphur has a relatively unmarked upperside in the male, presenting a palette “unclouded” by dark markings. It is extremely similar to Marcellina Sulphur (P. marcellina); in fact, Marcellina and Eubule were long thought to be subspecies of Cloudless Sulphur, P. sennae (Linnaeus, 1758). Eubule tends to be a lighter yellow color, particularly on the upper surface. It also is believed to have fewer and lighter dark markings underneath. However, individual and seasonal variation makes distinguishing this species from Marcellina a difficult proposition. Range and Habitat. Eubule is a common species in the SE US, from which it wanders afar every year (as far north as Canada). This species cannot survive freezing temperatures, so it must re-populate northern areas each year. It is a likely stray into eastern NM. Life History. Larvae use at least species in the genus Chamaechrista (formerly Cassia) in the Fabaceae. Partridge Pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata) is a common host in the eastern US; it has been found within 25 miles of our eastern border. Several species in the genus Senna are found in NM and are likely hosts as well. Eubule breeds year-around in the southern part of its range and can have as many as 3 broods in northern areas once it repopulates those areas. Comments. “Eubule” in Greek mythology was an Athenian maiden who sacrificed herself to protect Athens following a vision from the Delphic oracle. Núñez, et al. (2019) believed Eubule to be a subspecies of Clouded Sulphur (Phoebis sennae), resulting from repeated colonization of the US from the Greater Antilles, but Cong, et al. (2016) believed it to be a distinct species: Eubule Sulphur (Phoebis eubule). Both teams used DNA sequencing in their arguments, so their differing conclusions suggest how difficult this group is to resolve.

Phoebis philea (Linnaeus, 1763) Orange-Barred Sulphur (updated March 17, 2023)

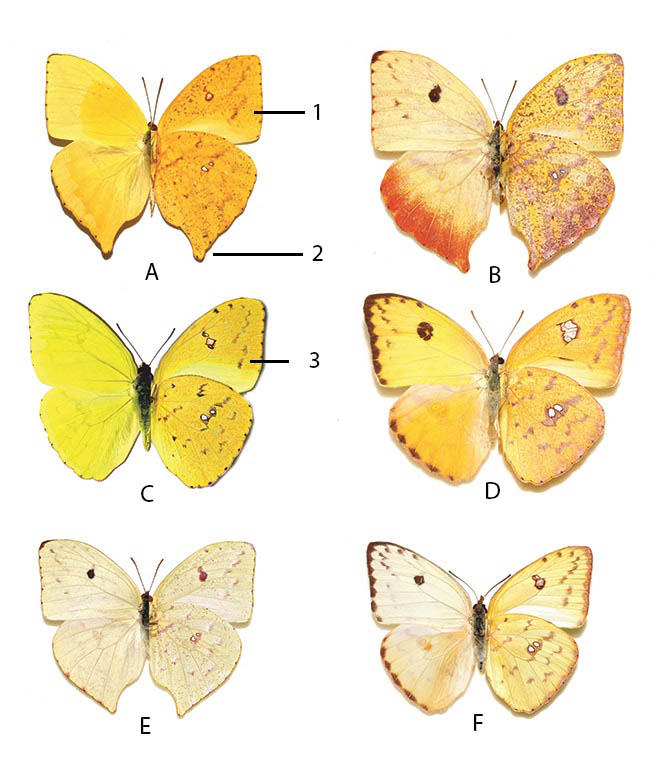

Description. Like all Phoebis species, Orange-Barred Sulphur is large and mostly yellow. Orange bars cross the dorsal forewing cell and dorsal hindwing posterior margins. Males are otherwise weakly marked. Females have dark marks ventrally and along the margins, with red suffusion near hindwing margins. Range and Habitat. Neotropical regions are home to this butterfly. Its northernmost breeding areas are the Caribbean islands and south Florida. Like its close relatives, it wanders regularly into other areas and infrequently into southern New Mexico (counties: DA,Gr,Hi,Va). LIfe History. Woody legumes (Fabaceae), such as Cassia species, are hosts for larvae. Phoebis philea has been found to breed occasionally in southeast Arizona. There is no direct evidence of reproduction in our state, but occasional breeding may occur in southern New Mexico. Flight. Our few records span April 17 to August 13 to November 4, suggesting sparse broods in spring, summer and autumn. Adults are most likely to be encountered during the monsoon influx from Mexico, when they enjoy nectar and moist earth. Comments. Our first report of Orange-Barred Sulphur is from near High Rolls, 6400′ (Ot), 13 July 1975 (Richard Holland).

Phoebis agarithe (Boisduval 1836) Large Orange Sulphur (updated August 11, 2024)

Description. Large Orange Sulphur is nearly uniform tangerine or apricot orange above and below in males. Females are more heavily marked, like other females in this genus. Albino females are known, and their paleness can look almost blue in the right light (see below). The ventral forewing has a diagnostic straight, diagonal, postmedian line of brownish striations. Range and Habitat. This tropical species breeds from Brazil north to western Mexico, south Texas and south Florida. Occasional strays are observed infrequently in southern New Mexico (counties: Ca,Cu,DA,Ed,Gr,Ha,Hi,Le,Ot,Ro,So). Look for them in riparian canyons and other desert oases, usually below 5500′ elevation. Life History. Shrubby legumes (Fabaceae) are the larval hosts. Lysiloma watsonii is used in southern Arizona (Bailowitz and Brock 2021). Scott (1986) reported that Pithecellobium species, Cassia species and Inga species are used elsewhere. There is no evidence of reproduction in New Mexico, but it is not out of the question. Flight. Most records of adults here are from the August rainy season. Early and late records are June 18 and December 7. This butterfly is very fond of nectar, such as thistles (Cirsium species). Comments. After Phoebis marcellina, this is our most frequently seen Phoebis species. Our first report was from Skeleton Canyon, Peloncillo Mountains, 15 August 1966.

Phoebis virgo (Butler 1870) Virgo Sulphur (updated May 4, 2024)

Description. The distinguishing feature of this large sulphur is the tail on the hind wing. Otherwise, it resembles Marcellina (formerly Cloudless) Sulphur with its yellow color on the upper surface. Individuals which have lost their tails may be difficult to distinguish from Marcellina Sulphurs. Clues would be the nature of the tail loss (Marcellina has a rounded hindwing, whereas Virgo has the hindwing produced which may be evident depending on how much of the hindwing was lost); the broken angled line on the underside of the hindwing has the lower portion of that line relatively straight in Marcellina, more angled towards the center in Virgo. As in Marcellina Sulphur, females occur in yellow and white forms. The yellow female Virgo may have extensive orange on the trailing edge of the hindwing. Range and Habitat. This tropical butterfly is a rare stray to the southwest US; its normal habitat is Mexico and points south. It has been recorded six times in SE Arizona (Bailowitz & Brock 2021) and one of those records was east of Douglas, AZ, within 25 miles of Guadalupe Canyon in New Mexico. Life History. Larvae are expected to use one or more legumes (Fabaceae), but reproduction is not expected in the US. Flight. In SE Arizona, records range from August to November, during and following the monsoon, and that would be the most likely time to find one in New Mexico. Comments. Virgo is a member of a three-part complex of very similar “tailed” sulphurs that were formerly considered as one species, Tailed Sulphur (Phoebis neocypris (Hubner)). Recent DNA studies by Nunez et al. (2019) determined that each member of the complex, including Virgo, was a fully distinct species. Naturalists hoping to see this species in NM should look in Guadalupe Canyon but should not expect to see one.

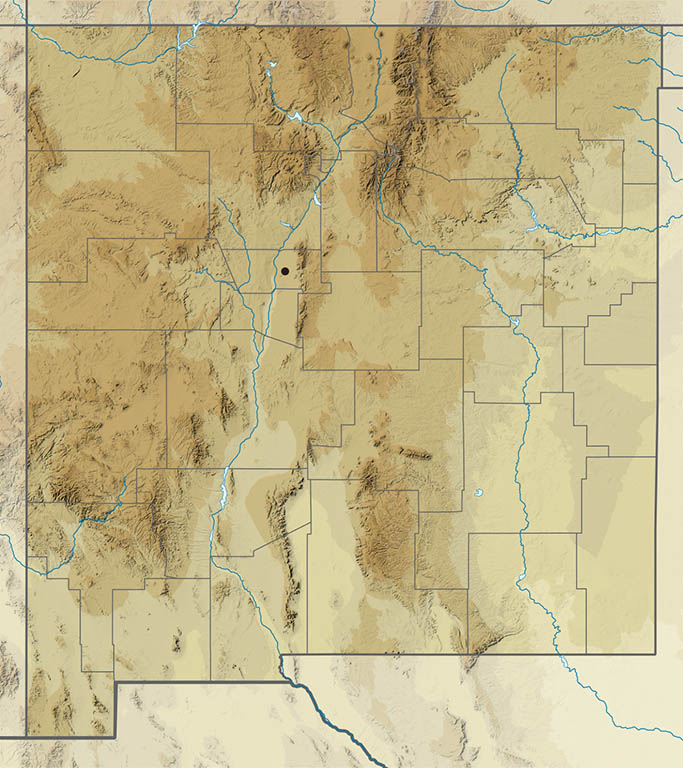

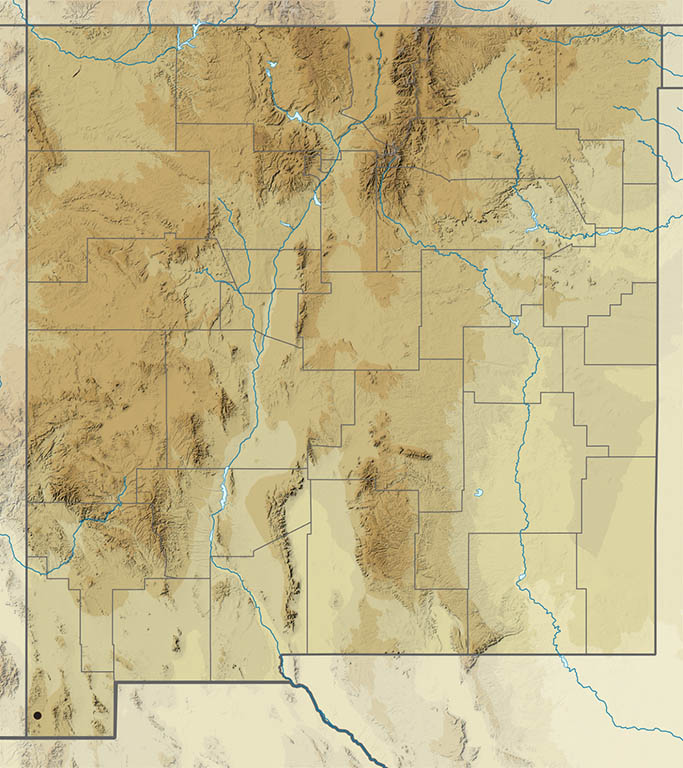

Aphrissa statira (Cramer, 1777) Statira Sulphur (updated January 20, 2024)

Description. This large sulphur is markedly two-toned, with the marginal and submarginal upper surface white to pale yellow and the basal area lemon yellow. Males may have a dark apical band on the FW, or they may be immaculate. Females have the marginal apical band, which extends almost to the anal angle of the FW. Females also have a dark cell spot. The ventral surface of males is immaculate, whereas the ventral surface of the female mirrors the markings on the FW, and there are some faint dots on the VHW. Females are decidedly pinkish on the margins of the ventral surface. Range and habitat. Statira Sulphur was observed by Mike Toliver in his back yard in Albuquerque in the mid 1960s (probably 1964). Unfortunately, he didn’t record the date. The specimen nectared on Buddleia right over his head, and his attempt to capture it failed. Statira’s normal range is south Texas and south Florida, south to Argentina. Strays have been found as far north as Kansas. Life history. Caterpillars feed on leaves of Fabaceae, including (in Florida) Dalbergia ecastophyllum and Calliandra. Three species of Calliandra occur in southwest New Mexico, but reproduction is unlikely. Flight. Statira flies all year in the tropics and subtropics. Vagrants in New Mexico are most likely to show up from July to September. Comments. Any Statira found in New Mexico will probably be strays; in addition to Toliver’s sight record from Albuquerque, it has been recorded in El Paso, TX. Southern New Mexico observers, be on the lookout!