by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver (updated March 15, 2022)

Swallowtails (Papilionidae). Swallowtails are our largest, most recognizable, and best studied butterflies. New Mexico’s 15 swallowtail species include familiar, widespread, tailed beauties like the Western Tiger, the rarely-seen Indra, and an ancient, tundra-dwelling Parnassian. Some are very infrequent, yet spectacular, strays like Polydamas, Ornythion, Broad-banded, and Palamedes. Swallowtail caterpillars possess some unique anti-predator adaptations, including an osmeterium. This structure is everted from the thorax when the caterpillar is threatened and the chemicals dispersed by it act as repellants. Most caterpillars in their early stages bear a remarkable resemblance to bird or lizard droppings, which may serve to hide them from predators or discourage predators from eating them. Photos for some of our species are needed, especially the subtropical strays. If you can fill a gap, we will be delighted to credit you for your image.

- Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius smintheus pseudorotgeri)

- Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor)

- Polydamas Swallowtail (Battus polydamas)

- Indra Swallowtail (Papilio indra minori)

- Baird’s Swallowtail (Papilio bairdii) Western Black Swallowtail; Old World Swallowtail; Papilio machaon bairdii; brucei

- Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes asterius) Papilio polyxenes rudkini ; pseudoamericus

- Anise Swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon) nitra; gothica

- Broad-banded Swallowtail (Heraclides pallas) Papilio astyalus;

- Ornythion Swallowtail (Heraclides ornythion)

- Western Giant Swallowtail (Heraclides rumiko) Heraclides cresphontes; Thoas Swallowtail;

- Palamedes Swallowtail (Pterourus palamedes)

- Spicebush Swallowtail (Pterourus troilus)

- Two-tailed Swallowtail (Pterourus multicaudata) pilumnus;

- Western Tiger Swallowtail (Pterourus rutulus) Pterourus glaucus; Pterourus rutulus arizonensis; Eastern Tiger; Three-tailed Tiger

- Pale Swallowtail (Pterourus eurymedon)

Parnassians (Papilionidae: Parnassiinae). Parnassians are tail-less tundra-dwellers that look more like large Pierids than swallowtails. Mating is concluded when males secrete a waxy plug onto the lower abdomen of females to prevent subsequent fertilization by other males. This ‘sphragis’ is considered evolutionarily primitive and is unique to Parnassians. Another primitive character is the pupa, which is formed in a loose cocoon. Parnassians may be distasteful to predators as the caterpillars sequester a bitter chemical from their food plants (Sedum in New Mexico).

Parnassius smintheus E. Doubleday 1847 Rocky Mountain Parnassian (updated January 5, 2024)

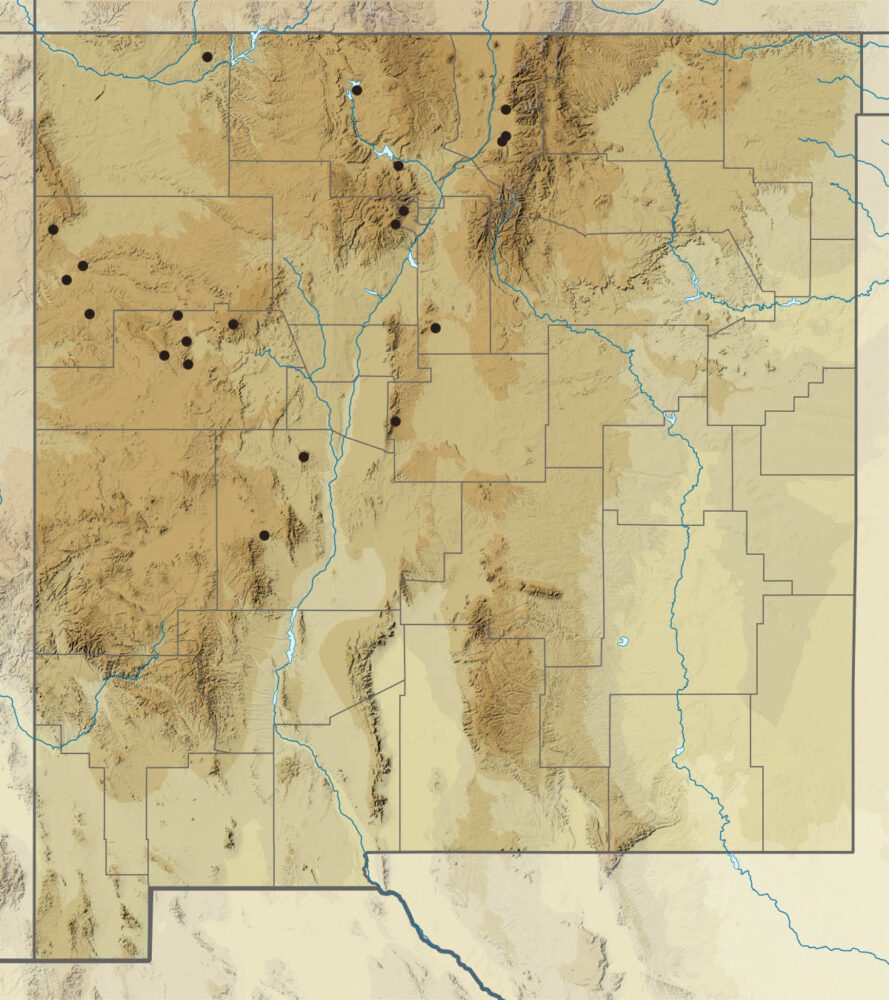

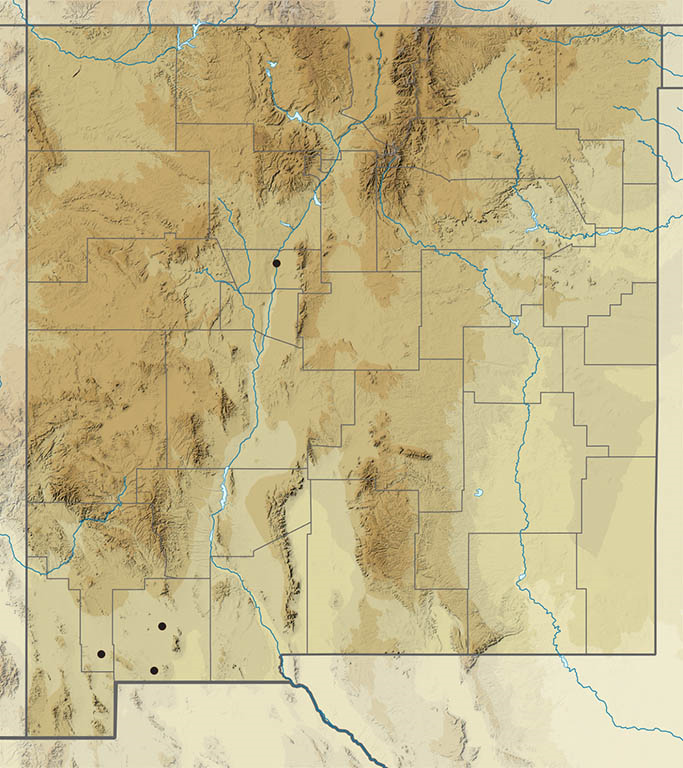

Description. This most “unswallowtail-like” swallowtail is unlikely to be mistaken for anything else. Rocky Mountain Parnassian has a 2-inch wingspan. The ground color is white, above and below, sometimes with a yellowish tinge, and with some red or orange spots on the hindwings. The edges of the wings (FW and HW on females, FW on males) are translucent. Wing bases are blackish, probably to aid thermoregulation. Range and Habitat. Parnassius smintheus is a high-latitude, high-altitude insect in the North American Cordillera from the southwestern Yukon to north-central New Mexico (counties: Co,Mo,RA,SM,SF,Ta). Here it is restricted to treeline Hudsonian Zone habitats in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, usually in open areas between 10,000′ and 12,500′ elevation. Slopes above the Santa Fe Ski Area represent its southernmost known occurrence in the US. Life History. Larval foodplants are all stonecrops (Sedum spp., Crassulaceae); three species (rhodanthum, integrifolium and lanceolatum) are likely suspects in New Mexico. Eggs are placed on or near the plants. Eggs or young larvae overwinter. Larvae are brightly colored: black (which probably helps in thermoregulation) with bright yellow spots on each segment. Rocky Mountain Parnassian is usually univoltine, but it may be biennial (one generation every two years) due to the short growing season at extreme high altitudes. Flight. New Mexico records span the period June 2 to September 27, but July is the best time to find them. Adults gather nectar from alpine flowers. Males patrol patiently across treeless tundra in search of females, which they may wrestle to the ground in attempts to mate. Supplemental Information. Rocky Mountain Parnassian is our only representative of this ancient group of swallowtails. Sangre de Cristo Mountains populations are consistent with Rotger’s Parnassian, Parnassius smintheus pseudorotgeri Eisner 1966, which also occupies Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. Intriguingly, Ferris (1976a) reported a specimen of pseudorotgeri taken by L. E. Chadwick on “Chama Peak” (11,500′-11,900′, 11-viii-1935) and attributed to Rio Arriba County, NM, but the only “Chama Peak” we know lies on the Continental Divide just north of the NM border, east of Chromo in Archuleta County, CO. It rises to more than 12,000’ and very likely has Parnassius habitat. We suspect the Chadwick specimen originated from Colorado, not New Mexico. Still, the highest Tusas Mountains east of Chama (RA) may yet be found to host P. s. pseudorotgeri. It has been found in adjacent Conejos County, CO, just across the border, so adjacent high areas of New Mexico, particularly privately owned Brazos Peak (11,288’) and Grouse Mesa (11,403’), should not be ruled out.

True Swallowtails (Papilionidae: Papilioninae). With wingspans of 3 to 6 inches, our 14 species of true swallowtails are large, colorful, confident flyers. The name “swallowtail” comes from a resemblance of these butterflies’ hindwings to the forked tails of avian swallows. Because they have been popular subjects of professional and amateur study for many decades, the life cycles, hostplants, and behaviors of our swallowtail species are reasonably well known.

Battus philenor (Linnaeus 1771) Pipevine Swallowtail (updated January 5, 2024)

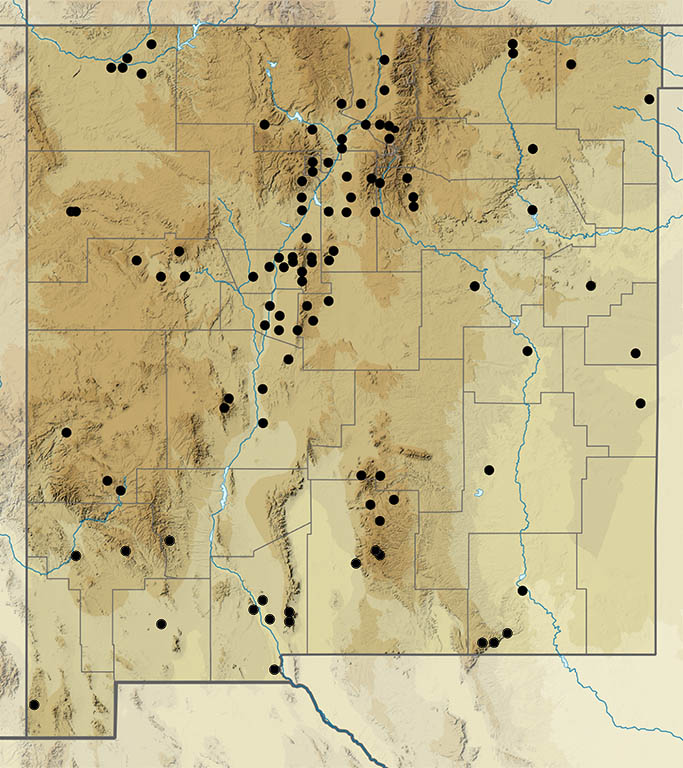

Description. This large species is black, but the hindwing above has widespread iridescent blue-green scaling and a submarginal row of cream-colored spots. Below, the glossy, steel-blue hindwing has a prominent submarginal row of yellow-orange spots within a bluish/greenish sheen, unlike any other swallowtail in the region. Because this species is so poisonous from chemicals derived from its larval foodplants, it serves as a model for a number of Batesian/Mullerian mimics; more on that below. Range and Habitat. Pipevine Swallowtails breed year-round in Mexico, southern Arizona, and much of the southeast US. Larvae have been found in southwest New Mexico (counties: DA,Hi,Lu) in April, May and August, so it breeds there as well. Adults are strong flyers and wander widely, accounting for all records in central and northern New Mexico (all counties except LA,MK,RA,Sv,SJ), where there are no native hosts on which to place eggs. Strays eventually will be found statewide. Life History. Larvae eat only plants in the Pipevine Family (Aristolochiaceae). Aristolochia watsonii, (Watson’s Dutchman’s pipe, southwestern pipevine) a vine of desert arroyos, is the only known host in New Mexico. Plants in this family contain chemicals that render larvae and adults of Battus philenor poisonous. Larvae come in two forms, black and bright orange-red, advertising their unpalatability. Eggs are laid in clusters on the foodplant. Unusually for swallowtails, the eggs are coated with a nutritious excretion which helps young larvae survive. In early instars, caterpillars feed communally, but in late instars they feed in solitude. Flight. In southern deserts, adults are in flight by spring; two or more additional broods are hatched before winter cold. Our records fall between February 15 and November 11. Numbers peak in April, then rise again to peak from June to August when strays to central and northern New Mexico are most frequent. Both sexes are fond of nectar, where adults beat their wings rapidly while siphoning. Males are casual hilltoppers, where their likeness to female Papilio polyxenes can confuse males of the latter. Comments. Because this species becomes so noxious from chemicals sequestered from its larval foodplants, it serves as a model for a number of Batesian or Mullerian mimics. Potential mimics of the Pipevine include females of Baird’s Swallowtail (Papilio bairdii), of Eastern Black Swallowtail (P. polyxenes asterius), of the “nitra” form of Anise Swallowtail (P. zelicaon) and the dark form of female Eastern Tiger Swallowtails (Pterourus glaucus glaucus). Some females of the Ornythion Swallowtail (Heraclides ornythion) also resemble this butterfly. Both sexes of Spicebush Swallowtail (Pterourus troilus troilus) can appear similar to Pipevines. Even a non-swallowtail, the Red Spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis arizonensis) is a close mimic, only lacking tails.

Battus polydamas (Linnaeus 1758) Polydamas Swallowtail (updated October 25, 2022)

Identification Marked by its tailless morphology, a trait shared by few swallowtails, and its dark wings with green lunules, Polydamas is very distinctive. It lacks the iridescent blues of its sister species, Pipevine Swallowtail; there is a yellow submarginal band on both forewing and hindwing. Range and Habitat. This species is Neotropical, ranging south to Argentina and north to the southern US. It breeds as far north as south Florida and south Texas, but it is only a rare stray in the interior US. The only NM record is from Mahoney Wash, Florida Mountains (Lu), on 12 May 1985 (S. Cary). Life History. As is true of all Battus species, Polydamas larvae eat plants in the Aristolochiaceae, but there is no evidence of breeding or reproduction in the southwest US. Polydamas is a strong flyer and adults come to nectar. Comments. There are six records of this species from SE Arizona (Bailowitz and Brock 2022). All are in the summer – June to August. It is a rare influx species in the SW. A female form of Broad-banded Swallowtail (Heraclides ornythion) and a female form of Ornythion Swallowtail (Heraclides ornythion) are apparent mimics of Polydamas.

Papilio indra Reakirt 1866 Indra Swallowtail (updated January 12, 2024)

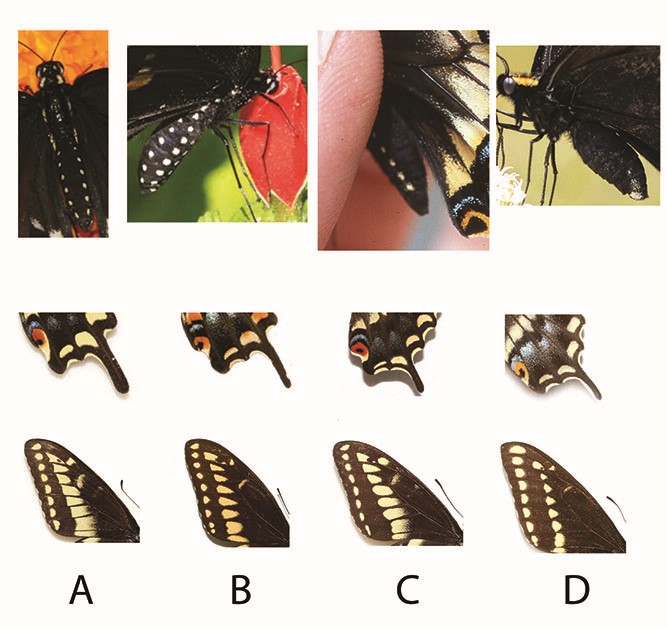

Description. Indra is one of four very similar “black” swallowtails; compare it with Eastern Black, Baird’s (= Western Black), and Anise Swallowtails. Indra differs by having a black abdomen with a single yellow side patch near the posterior end; no yellow abdominal dots are visible from above. The postmedian yellow band on the dorsal hindwing is reduced to a narrow strip. The submarginal blue band is well developed. Tails are short or stubby for some populations, but those in the Four Corners, like ours, have tails of normal length. The red eyespot near the tails has a large block dot that touches the wing margin. Range and Habitat. This archetypical western butterfly occurs from southwest British Columbia to northern Baja California and east to the Four Corners and South Dakota. It is an Upper Sonoran Zone to lower Transition Zone insect. Certain geographic races of this butterfly are restricted to some of the most starkly beautiful, least accessible lands in the Southwest. So far, Indra appears to be of limited extent in northern New Mexico (counties: LA,MK?,RA,Sv,SJ,SF,Ta,Va?), but that could be a function of few people looking in the right places. Life History. In Colorado, Indra Swallowtails use several larval hosts in the Apiaceae; most are strongly scented desert shrubs including Cymopterus purpurea, Aletes acaulis, Harbouria trachypleura and various species in the genera Lomatium, Pteryxia and Tauschia. Specific hosts in NM remain unknown. Pupae are drought-adapted and able to diapause for more than one year when necessary. Flight. We have several documented observations of adults spanning May 27 to August 8; observations of mature larvae span June 15 to August 12. Most observations from elsewhere are clustered in May. Inconveniently for humans, males patrol the rockiest ridges and high clifftops within the general habitat, then perch on the ground below summits. Thankfully, adults will come to nectar. Comments. Our populations belong to subspecies Papilio indra minori Cross 1937. Ralph Moore’s photos (below) were taken at the Colorado type locality for subspecies minori. New Mexico has a small but growing number of credible records. One old specimen was sent east from Fort Wingate (MK) c. 1917 by John Woodgate. A second specimen resides at the Utah Natural History Museum, taken in 1961 by H. Hall at Navajo Dam (SJ). Recently, R. Friedrichs found a female at Wild Rivers Recreation Area (Ta) and made the first live photos of this species in New Mexico. Most recently, it was (re)discovered in Los Alamos County, adding credibility to older records from Bandelier National Monument by Carl Cushing. Recent posts of photos of Indra larvae to iNaturalist have been very helpful (see photo below). Other iNaturalist posts suggest that Apiaceae species proven to host Indra elsewhere also can be found in the Manzano, Organ, San Andres and Guadalupe mountains.

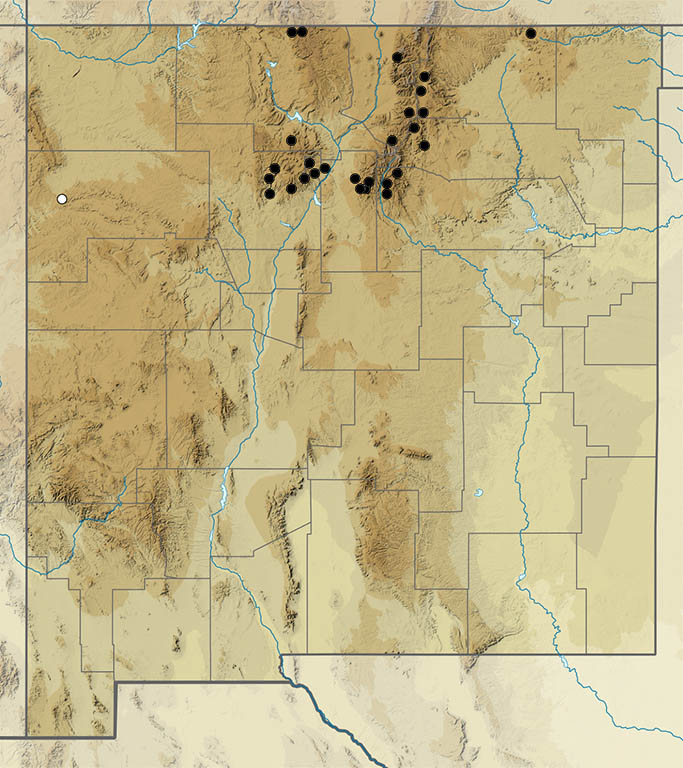

Papilio bairdii W. H. Edwards [1866] Baird’s Swallowtail (updated May 5, 2025)

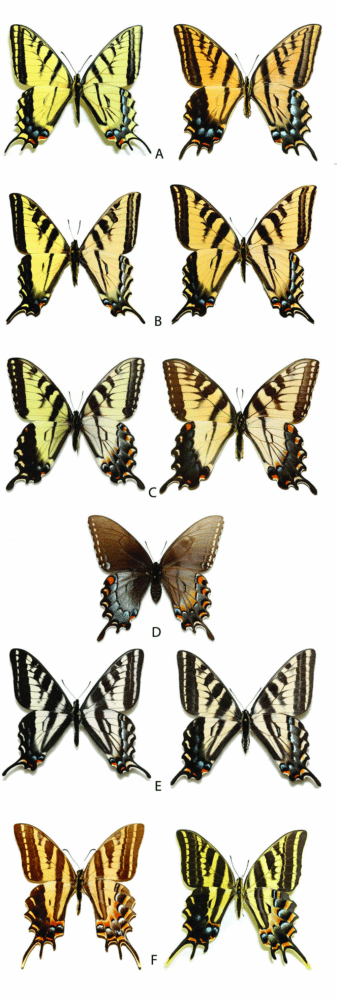

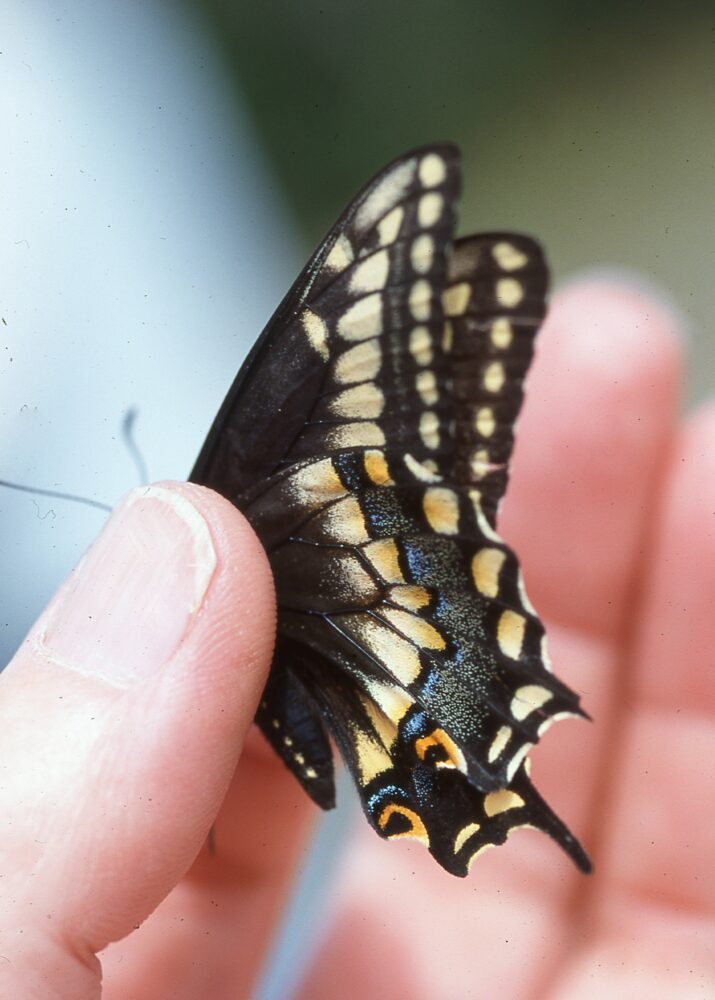

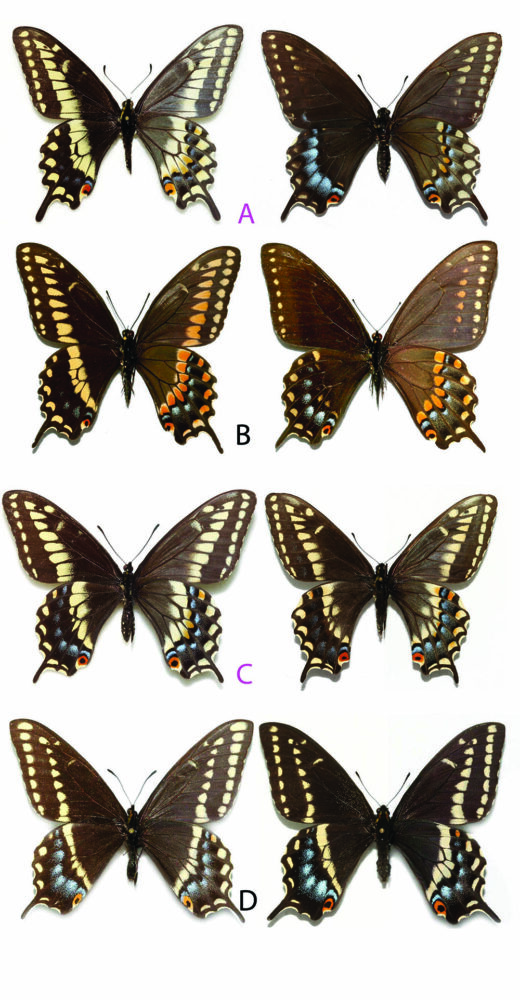

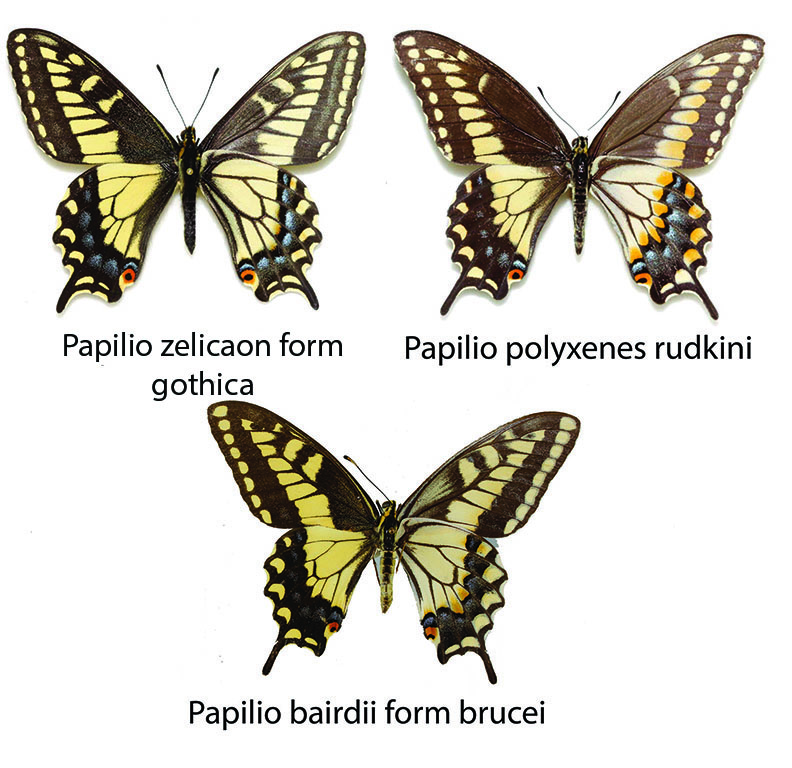

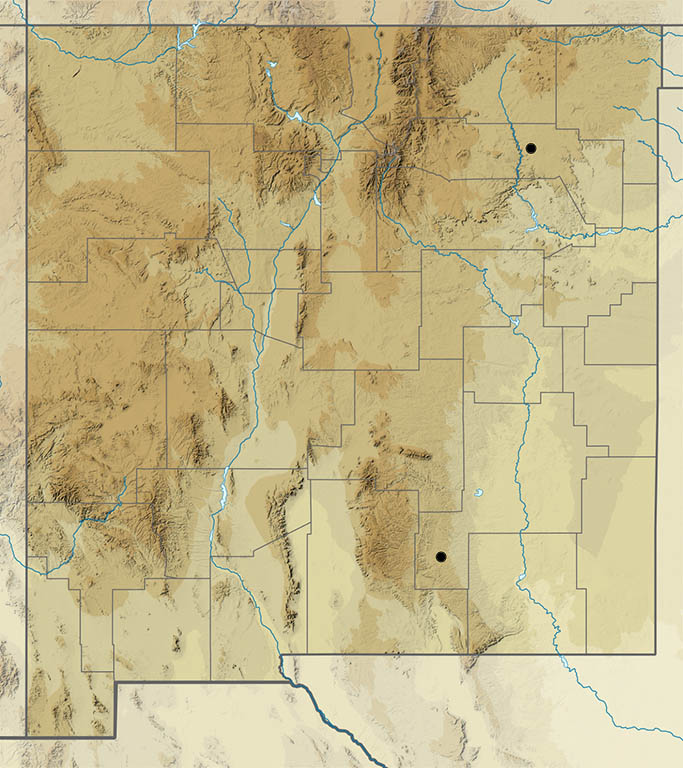

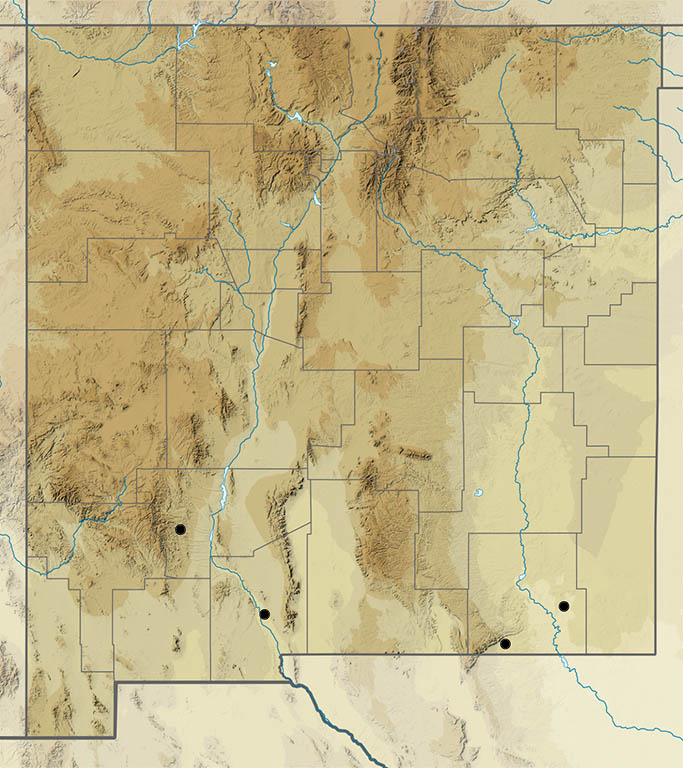

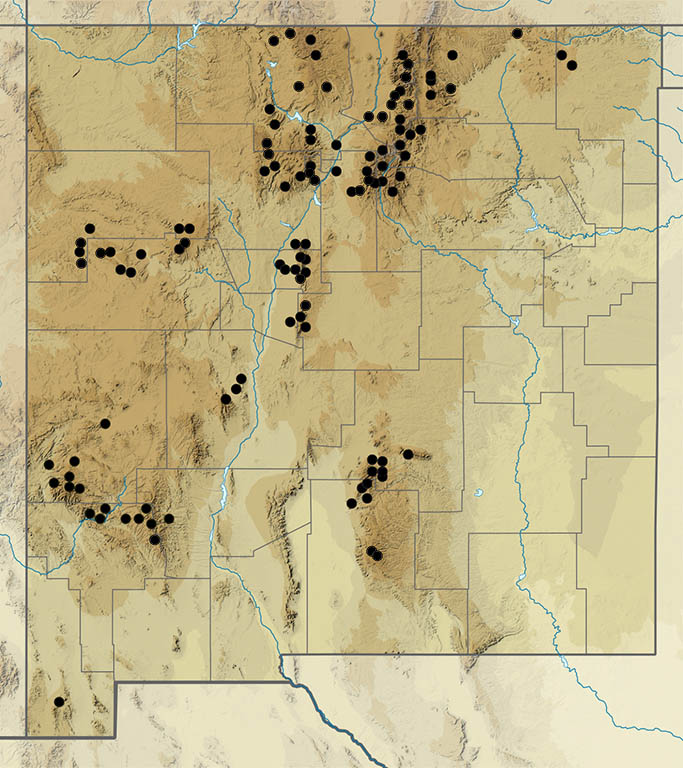

Description. Baird’s Swallowtail, or Western Black Swallowtail to some authors, has the same yellow marginal and postmedian spot bands sported by (eastern) Black Swallowtails. You can tell them apart in several ways, but close inspection is required: dorsal postmedian yellow spots are somewhat diffuse, not sharp-edged; the ventral hindwing postmedian band is pale yellow, not suffused with orange; the red eyespot near the hindwing tail has a flattened, black pupil touching the inner wing margin; and tegulae are yellow. The abdomen is marked like that of Papilio polyxenes. Papilio bairdii also occurs in form brucei W. H. Edwards, in which yellow areas are expanded to resemble Papilio zelicaon form gothica. Range and Habitat. In North America, Baird’s Swallowtail is a Great Basin insect distributed from California to New Mexico and north to Canada. It flies in Transition Zone savannas of New Mexico’s northwest quadrant (counties: Be,Ci,LA,MK,RA,Sv,SJ,SF,So,Ta,To), 6400 to 9200’. Black forms dominate in New Mexico; yellow form brucei prevails farther north but sometimes turns up here. Life History. Larvae eat only Artemisia dracunculus (green sage or wild tarragon; Asteraceae). A mature larva was seen feeding on this plant at Valle Canyon (LA) on 27 June 1998 (S. Cary, D. Hoard). This sage lacks the essential oils and pungent aromas typical of other sages. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Baird’s Swallowtails are bivoltine here, with peak numbers in May and again in July. Actual records span April 25 to September 1. Males patrol hilltops, sometimes jostling with Black and Anise Swallowtails. Adults come to nectar and moist earth. Comments. Close resemblance of Baird’s and Black Swallowtail has caused identification challenges. Specimens of alleged Papilio bairdii from central New Mexico (counties: Li,Ot,Si,So) were examined by Richard Holland and found to be Papilio polyxenes. Another extra-limital report (Gr) was considered uncertain by the collector himself (Ferris 1974). Resolution of those uncertainties clarified that Papilio bairdii is limited to New Mexico’s northwest quadrant. It has not been found east of the Jemez, Sandia or Manzano Mountains, nor south of the Magdalena Mountains. It flies in Bluewater Canyon below Bluewater Dam in Bluewater Lake State Park. Sometimes also called Western Black Swallowtail. Many older texts (even some not so old ones) treat this butterfly as a subspecies of Old World Swallowtail (Papilio machaon bairdii), but Papilio bairdii is now a full species per Condamine et al., 2023.

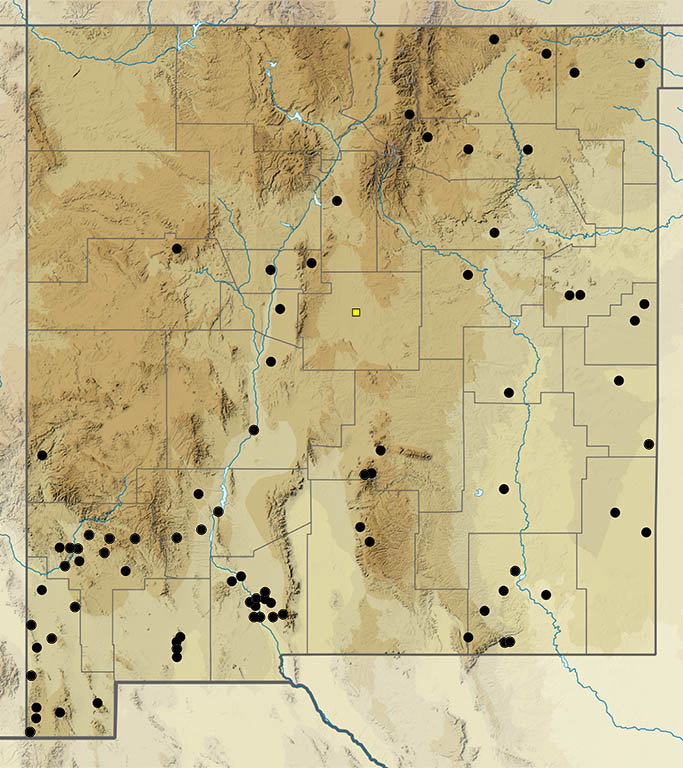

Papilio polyxenes Fabricius 1775 Black Swallowtail (updated August 13, 2022)

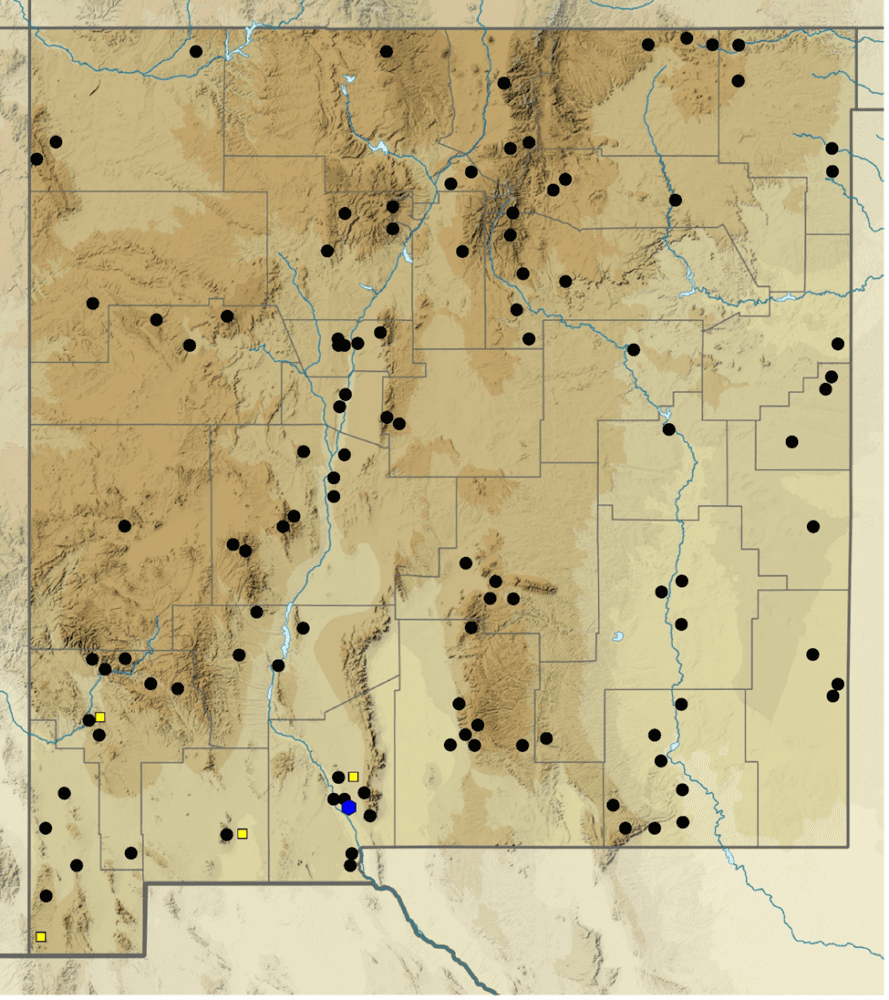

Description. Papilio polyxenes males are black with postmedian and marginal rows of yellow spots above and below, on forewing and hindwing. Between these two rows on the hindwing are blue spots. The ventral hindwing’s postmedian yellow row is suffused with orange. The hindwing tornus has an orange eye-spot with a black pupil that is round and centered. The black abdomen has four to six rows of yellow dots; tegulae are black. Females mimic Battus philenor with heavy blue scaling in place of the postmedian yellow band on the hindwing above. Range and Habitat. Black Swallowtail is resident east of a line that runs from Guaymas, Mexico, through the Four Corners (where Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico come together) to Saskatchewan. Its range includes all of New Mexico, where it lives in a variety of habitats as different as deserts, grasslands, cities and piñon-juniper woodlands, 3300 to 9000′ elevation. Life History. Females place their eggs on many different species of umbellifers (Apiaceae, or Carrot Family), including culinary herbs like anise, fennel and dill. Native hosts include water hemlock (Cicuta douglasii), poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), mountain parsley (Pseudocymopteris montanus) and cutleaf water parsnip (Berula erecta). Flight. Black Swallowtails complete three generations per year in southern New Mexico with peak numbers in April, July and September; extreme dates are January 14 and October 9. Northern New Mexico has two overlapping generations from May to September, peaking in June and July. Adults seek nectar. Males are strong hilltoppers, sometimes climbing above 12,000 feet. Comments. We expect the almost ubiquitous ‘Eastern’ version, Papilio polyxenes asterius Stoll, 1872, whose females frequent urban herb gardens to place eggs on dill, parsley and fennel in addition to native wild relatives. Infrequent spring individuals in southwestern New Mexico (Ed,Hi,DA,Ot) resemble southern California subspecies Papilio polyxenes rudkini (F. & R. Chermock 1981). We also see an occasional oddball that resembles form P. polyxenes asterius form pseudoamericus, for which the last two photos below show a female bearing male dorsal colors and a yellow striped abdomen.

Papilio zelicaon Lucas 1852 Anise Swallowtail (updated July 2, 2025)

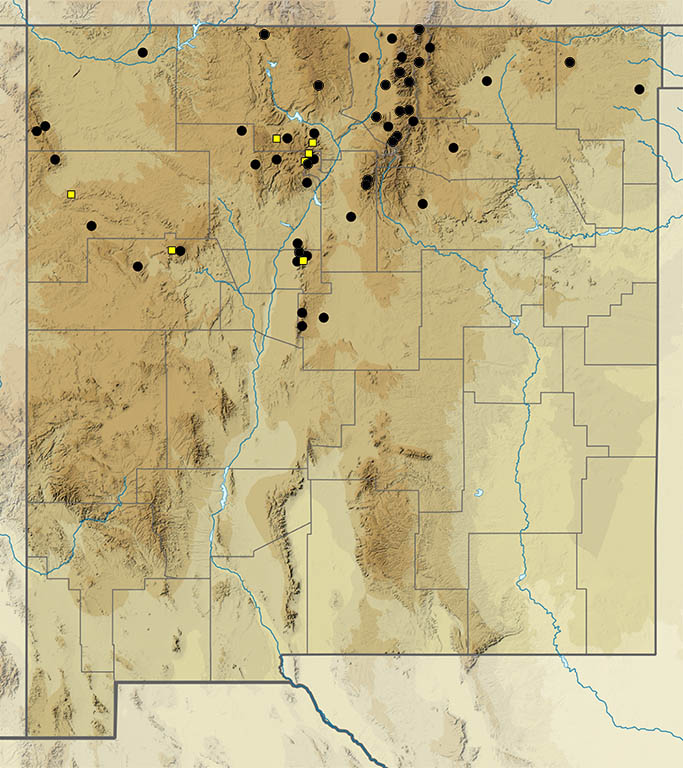

Description. Anise Swallowtail has black [form nitra (W. H. Edwards)] and yellow [form gothica (Remington)] versions. The latter version dominates in New Mexico and is arguably our most beautiful swallowtail. The postmedian yellow band is widened to the hindwing base. The black abdomen lacks the yellow racing stripes of Papilio bairdii fm. brucei, with which it is easily confused. Form nitra looks like Papilio polyxenes, but the abdomen has only one row of yellow dots on each side, instead of two or three. In both color forms of Anise, the hindwing red eyespot has a black pupil that is centered and round, like Papilio polyxenes. Range and Habitat. Anise Swallowtails live from Baja California to British Columbia, east to Saskatchewan and New Mexico. Here it lives in Canadian Zone coniferous woodlands and savannas in our northwest quadrant. Unlike Old World Swallowtails, Anise is distributed farther east to the eastern foothills of the Sangre de Cristos (counties: Be,Ci,Co,LA,MK,Mo,RA,Sv,SJ,SF,SM,Ta,To,Un). Form nitra is less widespread (counties: Be,Ci,LA,MK,RA,To). The altitudinal range of Anise Swallowtails here is 6000 to 12,800′; the higher reports are hilltopping males. Life History. Like Papilio polyxenes, Papilio zelicaon larvae will eat many Apiaceae. Oviposition is reported on Harbouria trachypleura and Conium maculatum (poison hemlock) in Colorado. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Anise Swallowtails have one extended annual generation in New Mexico. Adults fly from April 12 to August 27, but primarily May and June. Males aggressively patrol hilltops, which can be the most reliable places to find this swallowtail. Comments. In the semi-arid Southwest, many desert umbellifers have evolved oily compounds to reduce transpiration of precious water. Often each plant species has its own unique oils, with distinctive scents. These oils have become crucial links between herbivorous butterflies and their obligate host plants. Female swallowtails use sensors in their feet, or tarsi, to distinguish plants by their scents, thus identifying proper plants for oviposition.

Heraclides pallas (G. Gray [1853]) Broad-Banded Swallowtail (updated March 7, 2022)

Description. Though seen here but rarely, Broad-Banded Swallowtails resemble Giants and Ornythions (see below). On males, dorsal forewing submarginal yellow spots hug the wing margin. The dorsal forewing also has a yellow spot in the discal cell, but there is no yellow on the tails. Much darker, females lack the broad yellow bands and have one or no tails. Life History. Heraclides pallas is multi-brooded in the Neotropics, breeding from Argentina to south Texas. Adults occasionally stray farther north, and reports are known from southern Arizona and New Mexico. Larvae eat plants in the citrus family (Rutaceae), but reproduction is not expected in New Mexico. Range and Habitat. This butterfly was first recognized in New Mexico by Christopher Rustay, who videotaped a relatively fresh male nectaring in a patch of roadside alfalfa near Roy (Harding County) on 22 June 2003. His find prompted a review of specimens of ostensible Ornythion collected by the author in the Guadalupe Mountains of Eddy County in 1986. One ragged female proved to be Heraclides pallas; that specimen, taken in Bullis Canyon (Chaves County) on 28 July 1986, is in the Richard Holland collection, now in the C. P. Gillette Museum at Colorado State University. Comments. Until publication of Pelham (2019), this butterfly was previously called Papilio astyalus Godart. Females are apparent mimics of the Polydamas Swallowtail (Battus polydamas).

Heraclides ornythion (Boisduval, 1836) Ornythion Swallowtail (updated January 6, 2024)

Description. This beauty may be confused with Giant and Broad-banded Swallowtails. The postbasal band of dorsal hindwing yellow spots is narrower than on Broad-banded and broader than on Giants. Females have tails and may look like males, with yellow postbasal bands narrower and paler, or with dorsal yellow bands heavily suffused with brown. On the forewing above, the submarginal series of small yellow lunules remains separate from, and parallel to, the postmedian band of larger yellow spots. Life History. Ornythion breeds in the eastern tropics of Mexico, rarely entering southern New Mexico as a stray. Like Western Giants, Ornythion larvae eat plants in the citrus family (Rutaceae); there is no evidence of reproduction here, but Choisya dumosa and Ptelea trifoliata are potential warm season hosts. Range and Habitat. Only three New Mexico records are known; all fall between July 26 and August 27, during the summer monsoon season. It was first found by William H. Baltosser at the Las Cruces (DA) dump, 27 August 1975. A female taken at Rattlesnake Springs (Ed) on 26 July 1986 is in the Richard Holland collection, now in the C. P. Gillette Museum at Colorado State University. Most recently, Jan Richmond of Hillsboro (Si) photographed one nectaring at her butterfly bush on 5 August 2021. Comments. Females may be mimics of Pipevine Swallowtail.

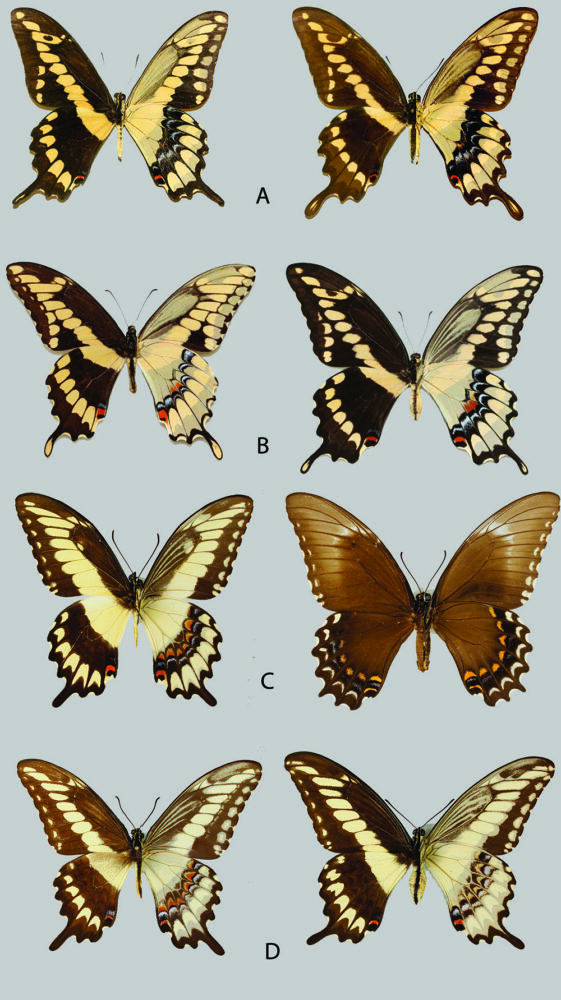

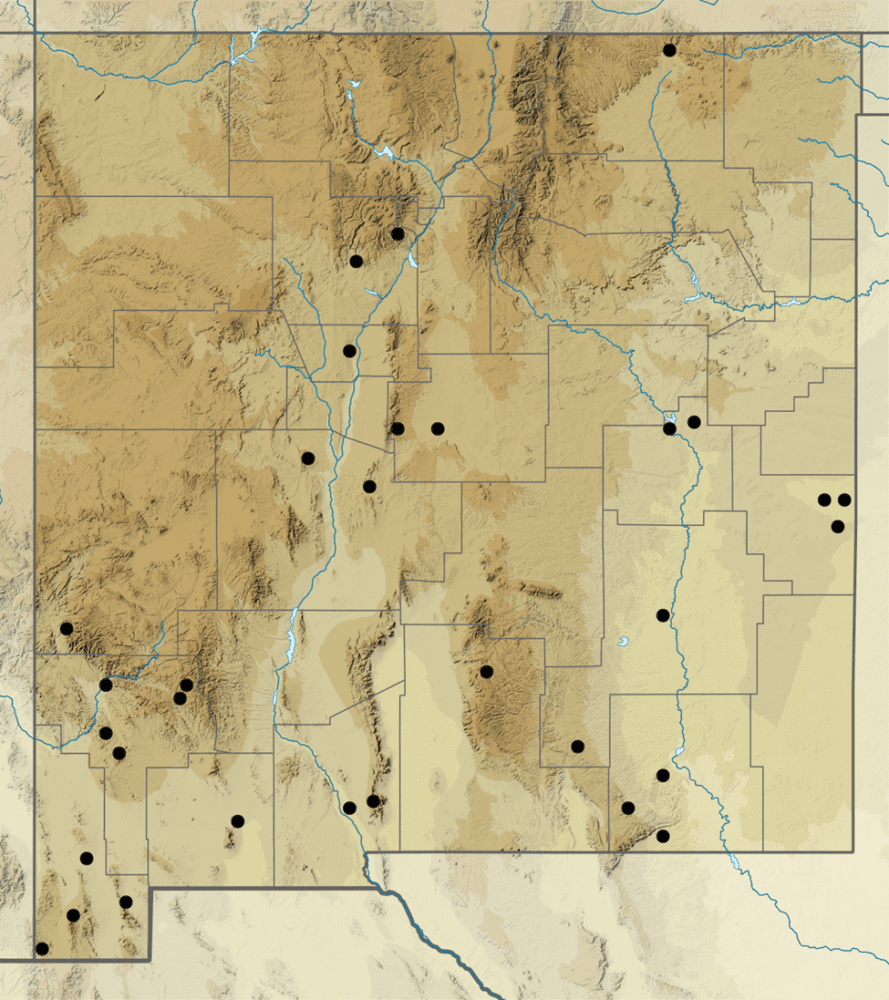

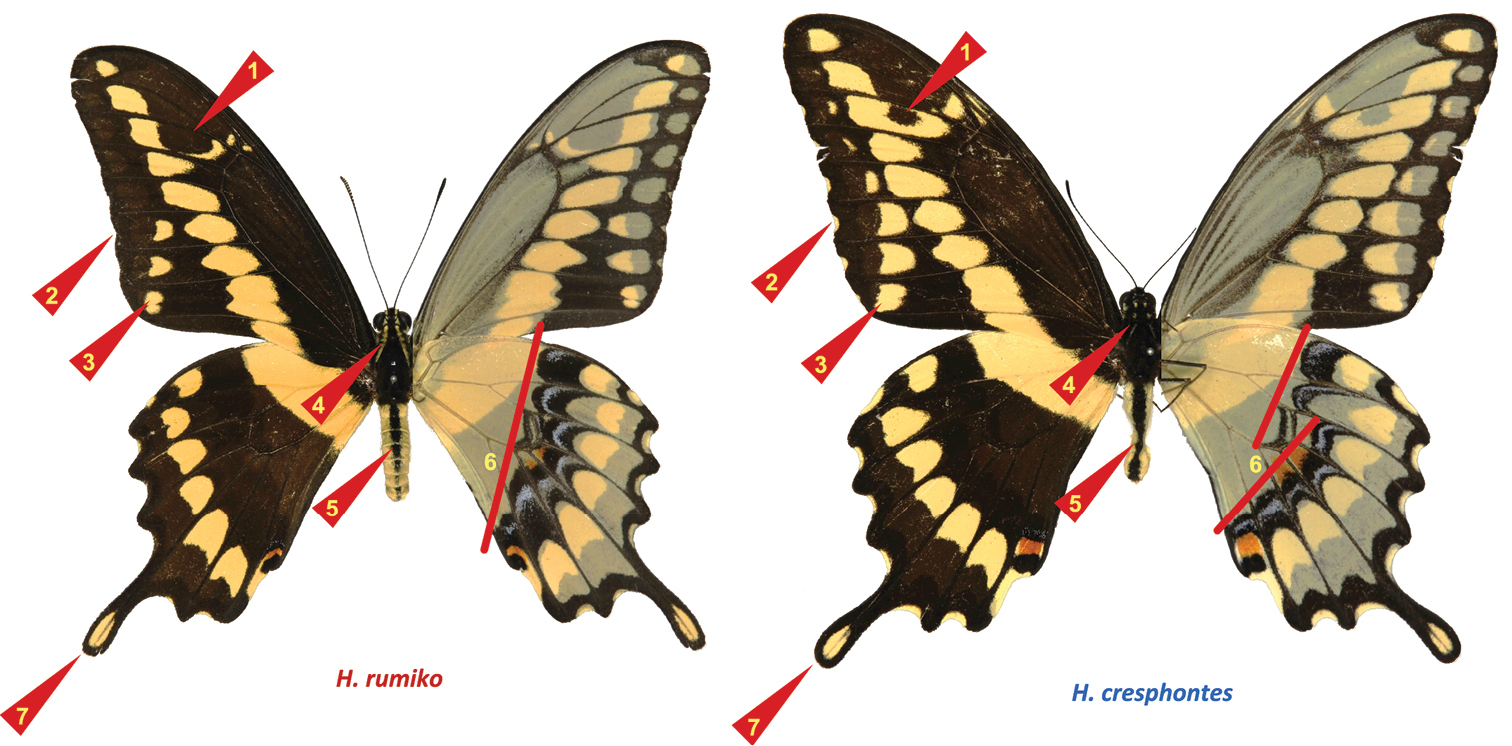

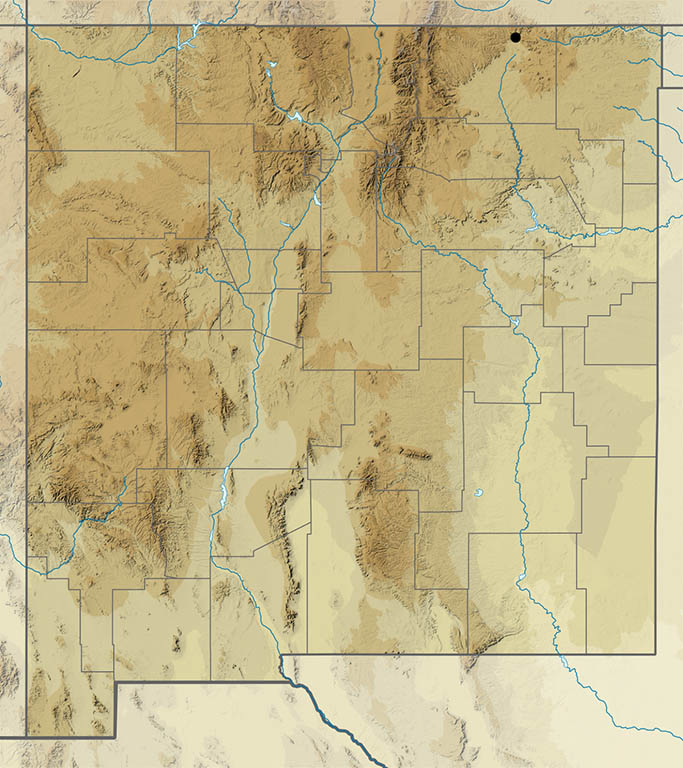

Heraclides rumiko Shiraiwa & Grishin 2014 Western Giant Swallowtail (updated July 10, 2022)

Description. Western Giant Swallowtail is large even for a swallowtail. On the upperside, warm yellow spot bands crisscross on a dark brown background. Each hindwing has a long, slender tail with a yellow spot. It can be confused with the very similar Giant Swallowtail of the eastern US. Range and Habitat. Western Giant Swallowtails live and breed in Tropical and Subtropical Life Zones from Colombia and Central America north into the southwestern US, from California to Texas. In good years, adults wander north into New Mexico. Western Giants reproduce occasionally along our southern border, producing fresh individuals late in the season, but no life stages survive our cold winters, even in southern New Mexico. It is almost routine in southern New Mexico and at low elevations (counties: Be,Ch,DB,Ed,Gr,Hi,Li,Lu,Ot,Ro,So,To). It strays much less frequently to northern New Mexico and higher elevations (counties: Ca,Be,Co,Sv). Life History. Larvae eat plants in the citrus family (Rutaceae). Seasonal reproduction occurs on our two native Rutaceae: Mexican orange (Choisya dumosa) and hoptree or wafer ash (Ptelea trifoliata). Oviposition also was observed on a non-native, planted rue (Ruta graveolens) in Albuquerque (Be) on June 22, 2020. In citrus orchards much farther south, larvae are pests, giving rise to its other English name: Orange Dog. Flight. Western Giant Swallowtails breed all year long farther south, appearing as occasional summer strays in New Mexico. Our records fall between April 21 and September 28, mostly July to September. Adults love thistle nectar. Comment 1. Many past authors treated Heraclides as a subgenus within the genus Papilio. Comment 2. Until recent DNA work by Shiraiwa, Cong and Grishin (2014), all swallowtails of this sort were lumped in with Giant Swallowtail (Heraclides cresphontes Cramer), which was thought to occur from Atlantic to Pacific across the southern US. Now we know that was a mischaracterization. Giants and Western Giants co-occur in Texas, so the possibility of finding eastern Giants in eastern New Mexico cannot be ruled out. The two are very similar but figures below indicate how to distinguish them. More Comments. Western Giant also can be confused with these strays: Broad-banded, Ornythion and Thoas Swallowtails. It is particularly difficult to separate from the Thoas Swallowtail, a species which is currently unreported from New Mexico or Arizona. It is supposedly possible to separate Thoas from the Western Giant by sliding one’s thumbnail over the end of the abdomen. If your nail slides over that area evenly, you may have Thoas; otherwise your nail will slide into a notch separating the uncas from the claspers. That would obviously only work on males!

Pterourus palamedes (Drury, 1773) Palamedes Swallowtail (updated October 27, 2022)

Description. This large butterfly is dark brown with a pattern of yellow spots generally reminiscent of an inflated Black Swallowtail. The hindwing is larger, more distended and more rounded than in Papilio polyxenes. The pattern of yellow, red and blue markings on the hindwing beneath is unlike any other North American swallowtail. Range and Habitat. Palamedes is a very rare stray that has been recorded only once in New Mexico, so do not go looking for it here. It is resident and breeds most of the warm season in subtropical southeast US along the Gulf of Mexico coast. Life History. Larvae eat various Lauraceae such as Sassafras sp. Our one record is from Raton (Co) in late June 1935, by J. R. Merritt. Flight. Although capable of wandering long distances, it rarely wanders upwind against the prevailing westerlies all the way to the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Comments. Some authors treat Pterourus as a subgenus within the genus Papilio. This present work follows Pelham (2021).

Pterourus troilus (Linnaeus 1758) Spicebush Swallowtail (updated July 30, 2023)

Identification. Spicebush Swallowtail most closely resembles Pipevine Swallowtail and is probably a member of the mimicry complex surrounding that species. It is distinguished by the green lunules on the margins of the dorsal surface of the wings and the greenish color of dorsal surface (leading to one of its other common names, the Green Clouded Swallowtail). On the ventral hindwing, the third red/orange spot from the inside margin (above the tail), in the median band, is smeared in this species, whereas in other dark swallowtails (for example, the Eastern Black Swallowtail) the spot is clearly outlined. Range and Habitat. This eastern species is almost unheard-of west of the Great Plains and is very rare in NM. It was definitively recorded in on July 10, 2021 (iNaturalist # 104560514) near Hachita, southern Grant County. Most recently, it was found in Albuquerque (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/174752130 24-vii-2023)! There are earlier unconfirmed records from Luna County by Carl Cushing (more on him in “Comments”): Deming, 28-ix-63; and Columbus, 28-ix-63. It could occur as a rare stray or perhaps as a stealth import in nursery plants. Life History. Larval hosts are trees in the family Lauraceae, including Spicebush (Lindera), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), Red Bay and Sweet Bay (Persea) and Camphor Tree (Cinnamomum camphora). The latter has been planted as an ornamental in Albuquerque and El Paso, and perhaps elsewhere in NM. None of the other larval hosts have been found in New Mexico and there is no evidence of reproduction here. In late instars, the caterpillars have two large bulging “eyes” on the thorax, which are presumed to mimic snake heads or tree frogs. This is believed to be a defense against vertebrate predators. All caterpillar instars hide in leaf shelters during the day. Young caterpillars cut a piece from the host leaf and fold it over to make their shelters, whereas older caterpillars fold entire leaves. Caterpillars come out to feed at night. Flight Period. The few records we have are from July and September. Comments. Carl Cushing, a lepidopterist formerly based in Los Alamos, shared his records with Dick Holland and Mike Toliver for the first edition of “Distribution of New Mexico Butterflies” in the mid-1990s. Those records included the Spicebush Swallowtail from Luna County. Some of Carl’s reports have been disputed because they seemed so “unlikely,” including his Spicebush Swallowtail records. However, Carl sent us doubtful records of Atrytonopsis hianna turneri from Frijoles Canyon which turned out to be correct.

Pterourus multicaudata (W. F. Kirby, 1884) Two-Tailed Swallowtail (updated March 7, 2022)

Description. Pterourus multicaudata has a warmer yellow ground color with long, narrower black stripes and a brighter appearance than the similar Pterourus rutulus. Each hindwing has one long and one short tail. With a wingspan that can approach 6 inches for females, this is our largest butterfly. Other tigers, currently unreported from New Mexico, resemble the Two-Tailed Swallowtail, but have more (P. pilumnus) or fewer (P. glaucus) tails and distinctive striping patterns. Range and Habitat. Two-Tailed Swallowtails live throughout western North America and south as far as Central America. In New Mexico they inhabit Upper Sonoran Zone riparian canyons. They usually are found below 7500′ but often wander up valleys to higher elevations. It is most common in southern New Mexico but is regular in much of the state (counties: all but Le). Life History. Several deciduous trees and shrubs are larval hosts. Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata, Rutaceae) is an important host in southern and central New Mexico. Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana, Rosaceae) is used in northern New Mexico. Various species of ash are used statewide, especially velvet ash (Fraxinus velutina, Oleaceae), which is often sold by nurseries as ‘Arizona Ash.’ City gardens attract this butterfly, and urban plantings of native ash allow it to reproduce. Larvae which are about to pupate turn brown and begin to wander some distance from their hosts to find a suitable site. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Adult Two-Tails begin to emerge with persistent warm weather in spring. There are two to three annual generations in southern New Mexico, with indistinct flight peaks from April through August. There are two broods in northern New Mexico, with peak numbers in July. Extreme flight dates are (January 29) March 22 and October 20. Two-Tailed Tigers patrol majestically along canyons, nectar at thistles and red flowers, and sip from wet sand. Comments. New Mexico has the nominate subspecies. A larva rescued from its journey across an asphalt parking lot in Santa Fe pupated on July 27, 1997; after wintering in an unheated garage, the adult emerged exactly 365 days later, on July 27, 1998.

Pterourus rutulus (Lucas, 1852) Western Tiger Swallowtail (updated September 19, 2022)

Description. Western Tiger is one of three New Mexico swallowtails with black ‘tiger’ stripes. Compared to Two-Tailed Swallowtails, Pterourus rutulus is smaller and lemony yellow with relatively broad, short, black stripes. Each hindwing has one full tail. Pale Swallowtail is white rather than yellow Range and Habitat. Western Tigers inhabit riparian settings in mountains of the western US, chiefly in Transition and Canadian Zone environments. They occupy New Mexico’s higher uplands (counties: Be,Ca,Ci,Co,Gr,Ha,Hi,Li,LA,MK,Mo,Ot,RA,Sv,SJ,SM,SF,Si,So,Ta,To,Un,Va), usually between 7000 and 10,000′ altitude. Life History. Larvae eat foliage of several deciduous shrubs and trees in several plant families. Among these are aspen (Populus) and willow (Salix) [both Salicaceae]; ash (Fraxinus, Oleaceae), wild cherry (Prunus, Rosaceae) and alder (Alnus, Betulaceae]. Urban plantings of shade-offering native ash trees (e.g., Fraxinus velutina) help this colorful species reproduce in urban and suburban settings such as Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Flight. Western Tigers complete one generation per year. Adults fly in early summer and are usually most abundant in June. Early and late dates in New Mexico are April 25 and September 2. Adults patrol up and down mountain stream corridors looking for mates and shopping for nectar. They sometimes gather at moist earth. Comments. Western Tiger is related to the Eastern Tiger, Pterourus glaucus (Linnaeus), with which it hybridizes in the northern Great Plains. Some experts lump them as one species. Others consider them separate and further divide southwestern populations into nominate Pterourus rutulus rutulus (most of New Mexico) and subspecies Pterourus rutulus arizonensis (W. H. Edwards 1883) (counties: Ca,Gr,Hi,So,Si). The latter entity has broader dark margins, but this difference is minor, and Pelham (2021) does not recognize it as subspecifically distinct from nominate rutulus. More Comments. Two other tiger-striped species (Eastern Tiger Swallowtail and Three-tailed Tiger Swallowtail) may eventually be found in the state. The Eastern Tiger has one tail and broader dark stripes, and the submarginal spots on the ventral FW are distinct, not merged into a line. The subtropical Three-tailed Tiger is true to its name and has three hindwing tails rather than two and the stripes on its wings are broader.

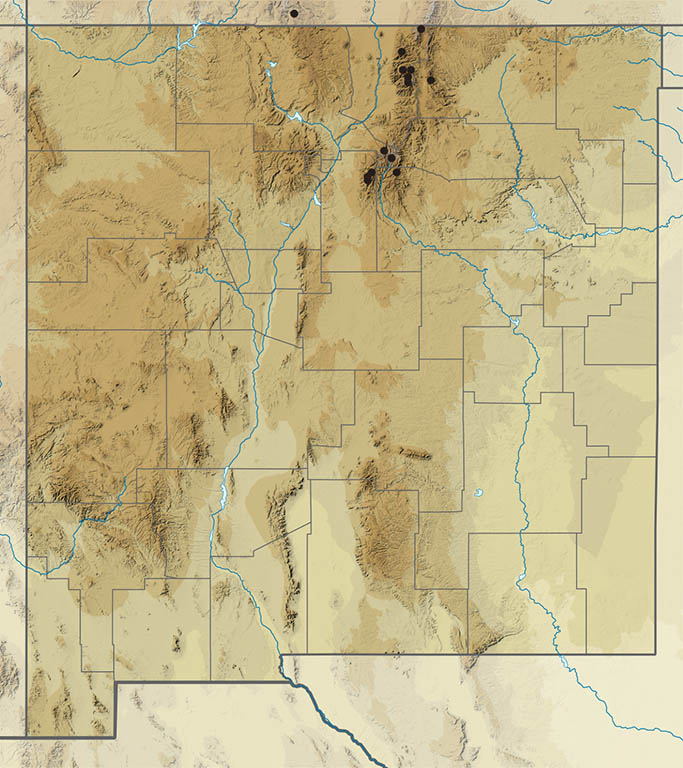

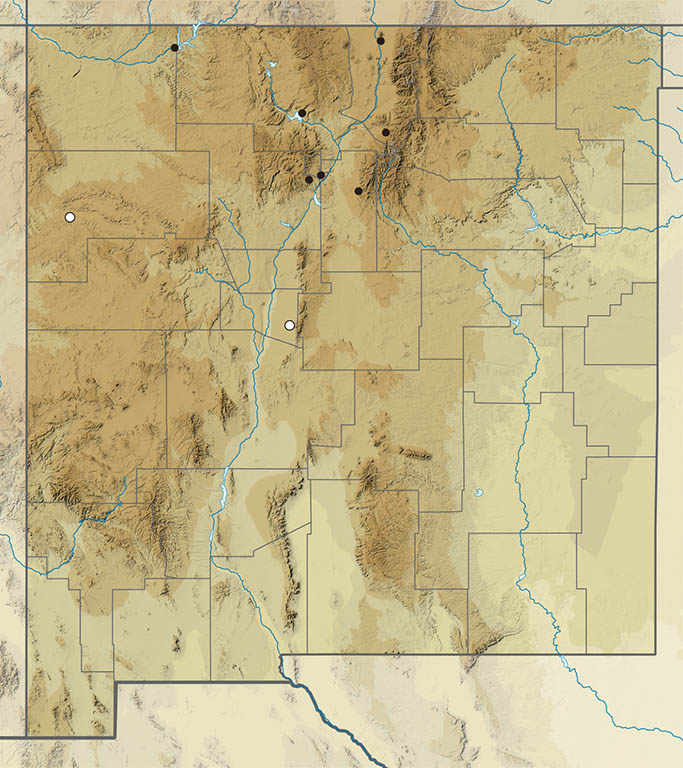

Pterourus eurymedon (Lucas 1852) Pale Swallowtail (updated October 26, 2024)

Description. Pale Tiger is about the same size as the Western Tiger, but it is creamy white rather than yellow. In addition, black stripes and black submarginal areas are broader, giving it a darker look. Each hindwing has a tail. Range and Habitat. This swallowtail occurs north through the Rocky Mountains to British Columbia, then south along the Sierra Nevada to Baja California. It has a more limited distribution in New Mexico than other Tigers (counties: Co,LA,MK,Mo,RA,Sv,SM,SF), 7000 to 10,600’. It is restricted to Transition and Canadian Zone meadows in our north-central mountains; it seems uncommon east of the Rio Grande. Life History. Fendler’s Buckthorn (Ceanothus fendleri; Rhamnaceae) is the host. Wild cherries (Prunus spp., Rosaceae) may suffice in a pinch. Chrysalids overwinter. Flight. Pale Tigers are on the wing from May 25 to July 24, mostly in June. Adults patrol through mountain meadows, stopping occasionally to sip nectar or moisture, but they are rarely seen in large numbers. Comments. The Los Angeles (California) County Museum curates our oldest specimen, collected near Ft. Wingate (MK) by John Woodgate on 3 June 1912. A recent survey of the Zuni Mountains (Holland 1984) failed to produce Pterourus eurymedon, casting some doubt on the true origin of Woodgate’s specimen. It is indicated on our distribution map by an open circle.