by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver (updated March 16, 2022)

Whites (Pieridae: Pierinae). Including the orangetips and marbles, there are 16 species of Whites (Family Pieridae: Subfamily Pierinae) in New Mexico. Most are of modest size, but some are larger. Some are very infrequent summer strays from farther south. The European Cabbage White is our only non-native butterfly. Larvae of most whites eat mustards (Brassicaceae). After a wet winter in southern New Mexico, four of the group put on quite a show as males quibble over prime, desert hilltop real estate while females shop through the selection of mustards (Brassicaceae) seeking the best oviposition sites for their offspring. Some members of this group withstand drought by staying in pupal diapause, sometime for several years, until winter rains make conditions favorable for larval hosts. It is possible that chemicals contained in the host plants render butterflies in this group unpalatable; Mike Toliver has witnessed only one attack by a bird on members of this group in more than 60 years of observation.

- Southwestern Orangetip (Anthocharis thoosa inghami); sara orangetip; Anthocharis thoosa coriande;

- Rocky Mountain Orangetip (Anthocharis julia prestonorum)

- Desert Orangetip (Anthocharis cethura pima)

- Large Marble (Euchloe ausonides coloradensis)

- Olympia Marble (Euchloe olympia rosa)

- Desert Marble (Euchloe lotta); Euchloe hyantis

- Florida White (Glutophrissa drusilla) Appias

- Pine White (Neophasia menapia magnamenapia)

- Chiricahua White (Neophasia terlooii)

- Great Southern White (Ascia monuste)

- Giant White (Ganyra josephina)

- Spring White (Sisymbria sisymbrii elivata) Pontia sisymbrii; Sisymbria sisymbrii transversa

- Checkered White (Pontia protodice) vernalis

- Western White (Pontia occidentalis)

- Becker’s White (Pontieuchloia beckerii)

- European Cabbage White (Pieris rapae) immaculata;

- Margined White (Pieris marginalis mcdunnoughii) Pieris napi; Pieris marginalis mogollon; Pieris marginalis siblanca

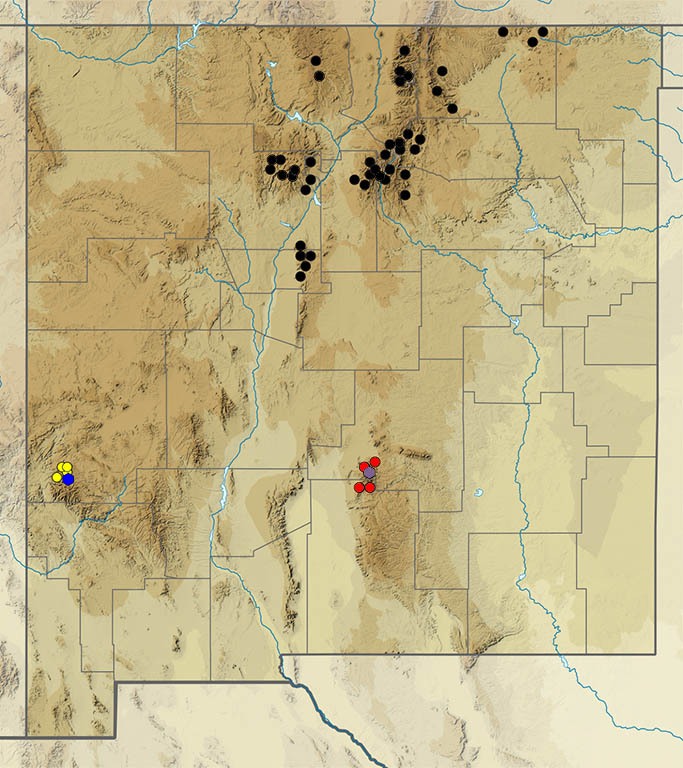

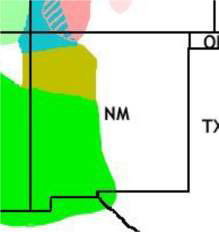

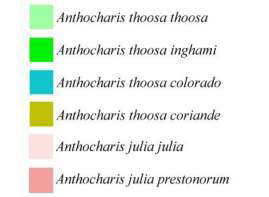

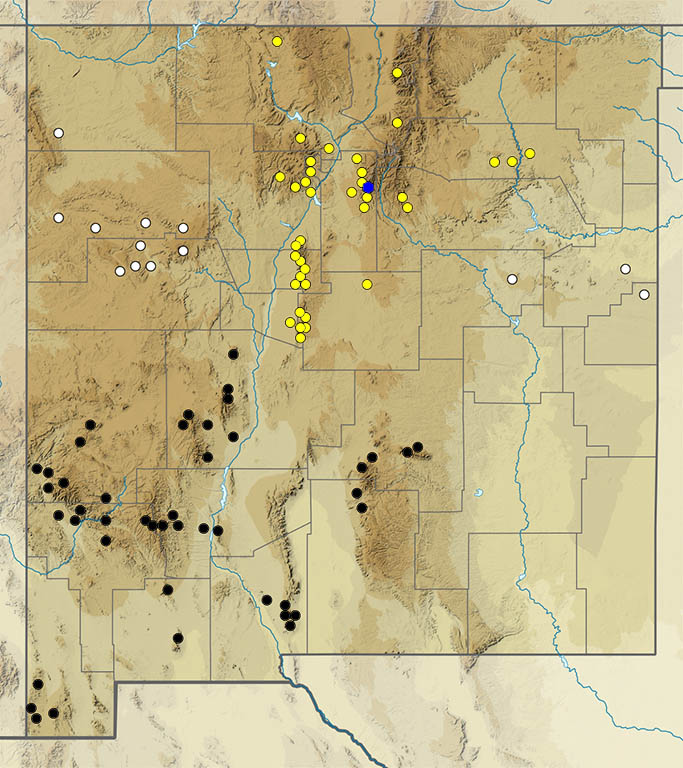

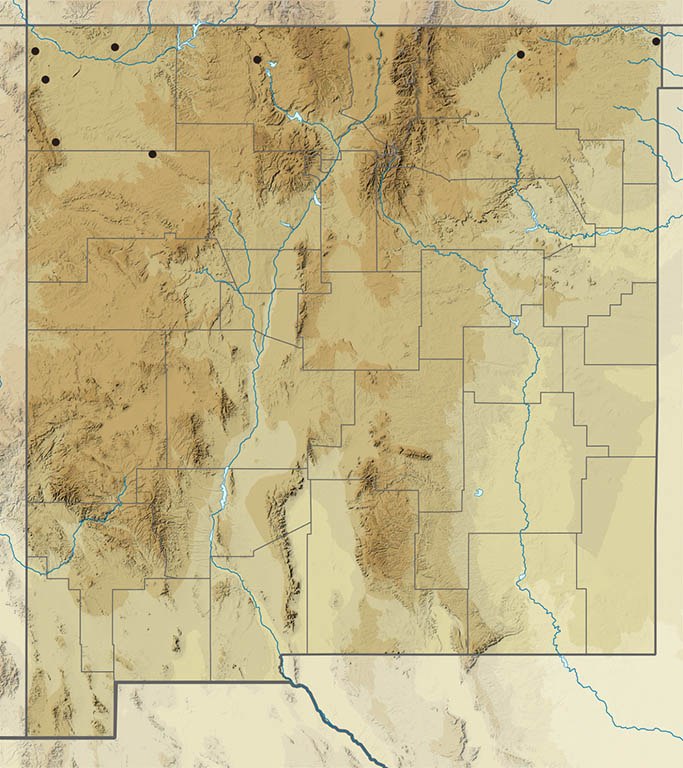

A word about the “Sara” Orangetips: The familiar “Sara” orangetips collectively occupy western North American habitats from Alaska to Baja California and from the West Coast to the Rocky Mountain Front Range. Taxonomist have vacillated between treating this wide-ranging assemblage as one species, Anthocharis sara, with many subspecies, or treating it as a complex of multiple species. The latest revision (Stout 2018) is a comprehensive work that has achieved much-needed consensus among the experts. By examining adult, larval and pupal characters, life history details and genetics, Stout discerned that three species comprised the “sara” complex. New Mexico does not have Anthocharis sara, the West Coast representative, but we do have the other two: Anthocharis thoosa (Southwestern Orangetip) and Anthocharis julia (Rocky Mountain Orangetip). These two taxa are difficult to distinguish from each other by examination of adult features alone. Nevertheless, we recommend focusing on making the best possible species-level determinations so we can get a better grip on the geographic occurrence of each in New Mexico. So far, geographic parameters for A. thoosa and A. julia in NM are thought to be as shown in the image below (from Stout 2018), which points to San Juan and Rio Arriba counties as the area to pay particular attention. Individual accounts for A. thoosa and A. julia follow.

Anthocharis thoosa (Scudder 1878) Southwestern Orangetip (updated January 9, 2024)

Description. Southwestern Orangetips are distinguished by bright orange dorsal forewing apical patches with black borders set against a white dorsal ground color. In females, the orange patch is reduced, the black borders are diffuse and the wing ground color sometimes is dusted with pale yellow. The ventrum of both sexes is mottled with scales that vary from dark green to almost black. It resembles A. julia, but as Stout notes, the ventral forewing black mottled band between the orange patch and the wing margin is pronounced on A. thoosa, but faint or obsolete on A. julia. Range and Habitat. Anthocharis thoosa lives in much of the interior West (AZ, UT) as well as much of New Mexico (all counties but Ch,Co,DB,Ed,Le,Ro,Un). Here, it is widespread in Upper Sonoran and Transition Zone savanna habitats, 4500 to 8500′ elevation. Life History. Mustards (Brassicaceae), particularly rock cresses (Boechera, formerly Arabis, spp.) are larval hosts. Paul Opler observed oviposition on Arabis sp. in Gallinas Canyon (Gr), 30 April 1990. Larvae ate Boechera perennans in the Little Florida Mountains (Lu) on 11 April 2003 (Jim Brock). Bailowitz and Brock (2021: 62) cited use of Guillenia lasiophylla, Streptanthus carinatus, Thysanocarpis curvipes, Descurainia pinnata and (non-native) Sisymbrium irio in southeast Arizona. Mustards sprout, bloom and senesce by late spring. By then, larvae have fed, pupated and entered diapause. It takes about two weeks to go from egg to pupa. Stout noted that Southwestern Orangetip typically passes two or more overwintering cycles before eclosing. Flight. Anthocharis thoosa is univoltine here with adults flying February 22 to May 29. Peak flight is March to April in southern New Mexico and a month later farther north. Males are persistent hilltoppers; females fly near the ground seeking mustards on which to place eggs. Adults come readily to nectar including willow and mustards. Comments. Stout (2018) indicates that southern, western and central New Mexico have subspecies A. t. inghami Gunder 1932, which can be called Southwestern Orangetip. In this form, black marks around the DFW orange patch are relatively thick, dense, dark and straight. Females often have a hint of yellow in the DHW discal area. Areas farther north (counties: Be,LA,Sv,SM,Mo,SF,Ta) seem to have A. t. coriande M. Fisher & Scott 2008, a recently recognized form described from specimens collected near Glorieta Pass southeast of Santa Fe. On this ’Glorieta’ Southwestern Orangetip, the DFW orange patch is bounded by black marks that are weaker, thinner, more diffuse, and curvy compared to inghami. Females do not have yellow on the DHW. Individuals with inghami and coriande phenotypes can be found in the range of the other, underscoring the poor definition of subspecies boundaries. A third named form, Colorado Plateau-based A. t. colorado Scott & M. Fisher 2008, probably occurs in northwest New Mexico, but documentation remains weak.

Anthocharis julia W. H. Edwards 1872 Rocky Mountain Orangetip (updated May 15, 2024)

Description. Nearly identical to the Southwestern Orangetip, observers will find it difficult to definitively identify this butterfly. Stout (2018) says “A consistent diagnostic difference in examining a series of adults of A. thoosa colorado vs. A. julia nr. prestonorum is evident in the ventral forewing black mottled band adjacent to the orange apical patch towards the wing margin which are either faint or obsolete in A. julia nr. prestonorum and are more pronounced in A. thoosa colorado even when the discal cell bars and connecting black borders are prevalent and similar on the dorsal surface of both species.” Range and habitat. Rocky Mountain Orangetip has the widest range of the three species in the “sara” complex (Stout 2018), living from northern Canada to northern NM. It prefers higher altitudes than Southwestern Orangetip, though the two species may occur together. Life history. Stout obtained ova of this species on Boechera spp. in nearby Archuleta Co., CO. It is likely species in that genus serve as hosts in NM as well. Rocky Mountain Orangetip pupae typically undergo one overwintering cycle. Flight. Adults are on the wing here from at least April 9 to at least May 14. Comments. Due to past confusion with Southwestern Orangetip, our understanding of this species in NM is limited. We need more observations and specimens from northern New Mexico (Rio Arriba, Taos and Colfax counties) to develop a clearer picture of Rocky Mountain Orangetips in our state. Todd Stout considers our New Mexico populations to be A. julia near prestonorum Stout 2012 (=’Southern’ Rocky Mountain Orangetip), by which he means it seems very close to subspecies prestonorum, but slightly different. It is also possible that nominate A. julia julia may be found in the mountains of Taos or Colfax counties.

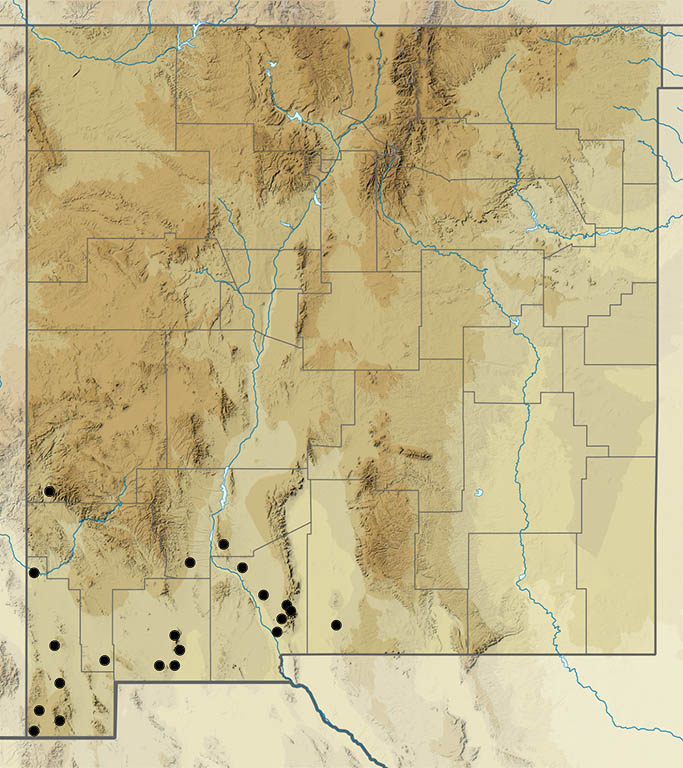

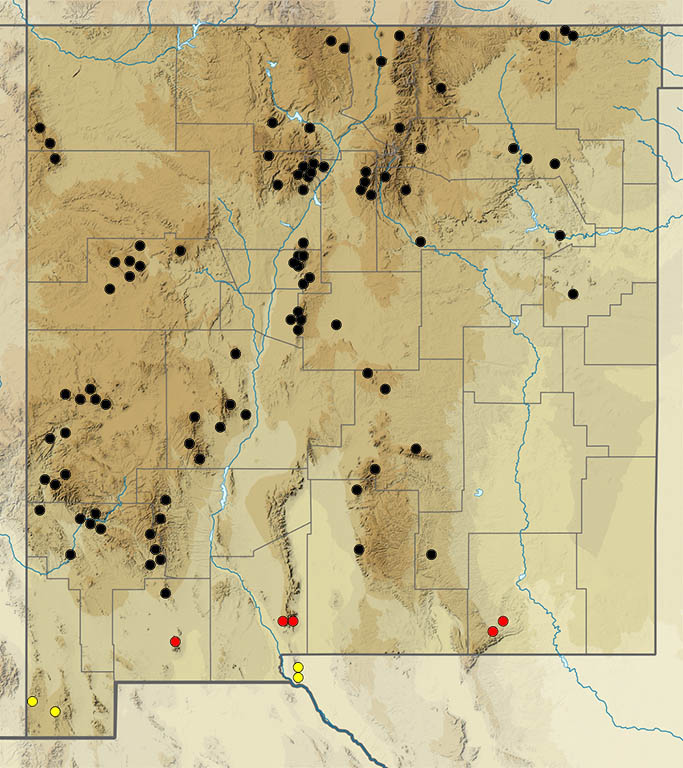

Anthocharis cethura Felder & Felder 1865 Desert Orangetip (updated May 26, 2023)

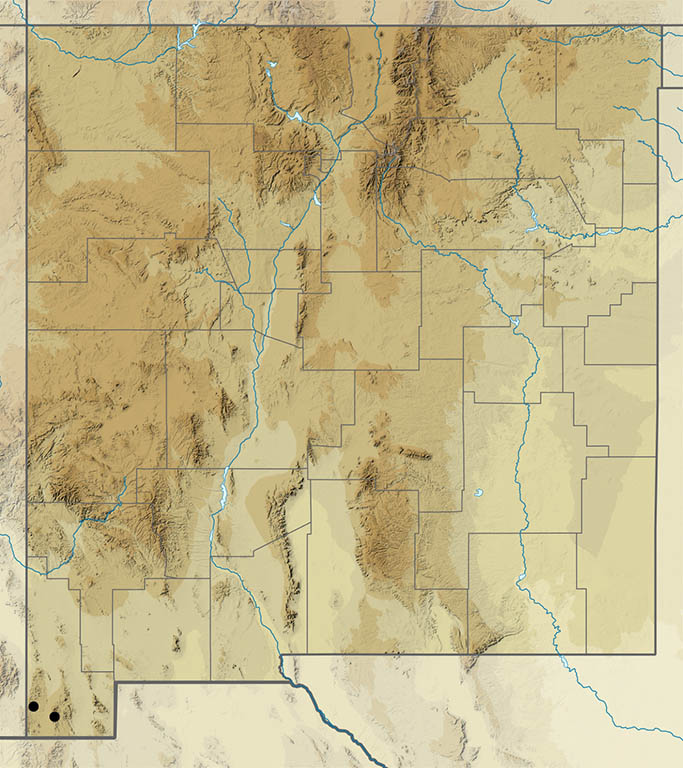

Description. Although basically white in other areas, Desert Orangetips are pale yellow in New Mexico, but otherwise much like the foregoing species. The ventral hindwing marbling is gray-green. The forewing orange patch is bounded by a black cell-end bar and black-and-white apical marks which tend to be broader than on Anthocharis thoosa. On males, the orange patch often suffuses beyond the apical edging, which tends to be sharply defined and more black than white. In comparison, females are larger; the apical edging seems smudged and whiter; and the orange patch can be reduced or pulled back within the black edging. Range and Habitat. Anthocharis cethura inhabits Upper Sonoran Zone deserts in northwest Mexico, southern California, Nevada, Arizona and southwest New Mexico. In our state it inhabits desert shrublands and grasslands from the lower Tularosa Basin westward, then north as far as Hatch and Silver City (counties: Ca,DA,Gr,Hi,Lu,Ot,Si), spanning elevations from 4000 to 5600′. Life History. Larvae eat various Brassicaceae including Guillenia lasiophylla, Streptanthus carinatus, Sisymbrium irio (a non-native), and Thysanocarpis curvipes (Brassicaceae). Larvae ate Descurainia pinnata at Rockhound State Park on 12 April 2003 (Jim Brock). Pupae overwinter. As with A. thoosa, diapause can be extended for multiple years to survive drought. It usually takes a winter with normal or greater precipitation to motivate pupae to break diapause and produce their adults the following spring. Flight. Nominally univoltine, adult Desert Orangetips emerge with warm early spring weather. New Mexico records span February 24 to April 24. Males hilltop alongside Southwestern Orangetips and Spring Whites. Comments. This species lived here anonymously until W. H. Baltosser found it in the Organ Mountains (DA) on 22 March 1977. Our populations belong to subspecies Anthocharis cethura pima W. H. Edwards, which some authors elevate to a full species.

Euchloe ausonides (Lucas, 1852) Large Marble (updated March 13, 2022)

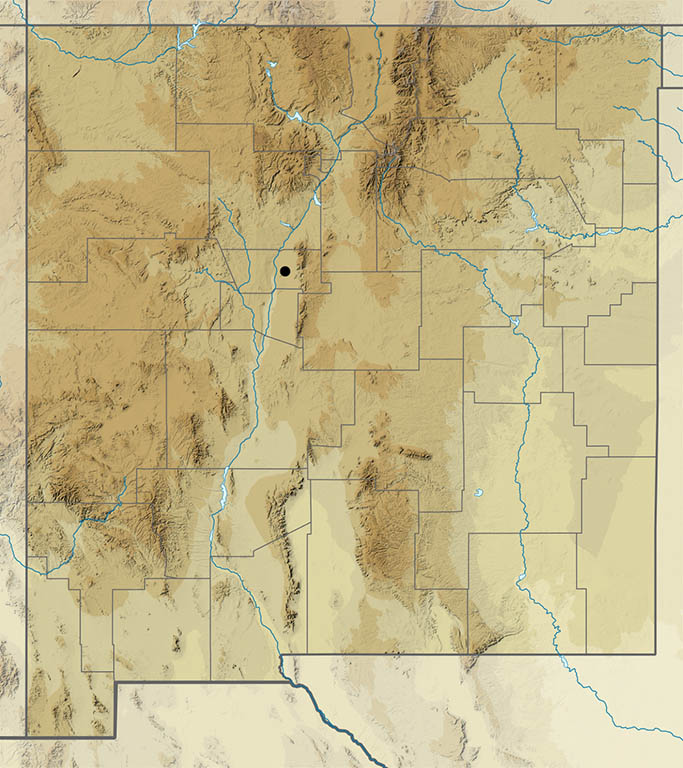

Description. All Euchloe species are of modest size with green ventral marbling, but no orange forewing apices. Large Marble has a white or cream ground color, dense, dark underside marbling, black marks at the forewing apex, and a narrow black bar in the forewing cell. Its name notwithstanding, it is no larger than our other marbles. Range and Habitat. This is the most alpine of all our Anthocharines. It lives from Alaska to central Canada, then south to higher mountains of the western US. It is a Transition to Canadian Zone dweller in our state, where it lives along streams and in high, moist meadows in our north-central mountains (counties: Be,Co,Mo,RA,SM,SF,Ta,Un?), usually 8000 to 11,000′. Life History. Alpine mustards (Brassicaceae) are larval hosts. Scott (1986) listed several genera, including Arabis, Barbarea, Descurainia, Lepidium, Raphanus, Sisymbrium, and Thelypodium. Larvae feed in summer; chrysalids overwinter. Flight. Euchloe ausonides adults fly in a single annual generation from early to mid-summer; our records span May 11 to August 9, concentrated in June to July. Adults fly weakly near the ground through alpine meadows, sometimes near treeline, frequenting streams and nectaring at meadow flowers. Comments. Some experts place Rocky Mountain populations in subspecies Euchloe ausonides coloradensis (H. Edwards, 1881), but variation across all North America is minor. The American Museum of Natural History in New York has a 1936 specimen from the Sandia Mtns. (Be). This represents the southernmost extent of this species, but it has not been found there since.

Euchloe olympia (W. H. Edwards, 1871) Olympia Marble (updated March 10, 2022)

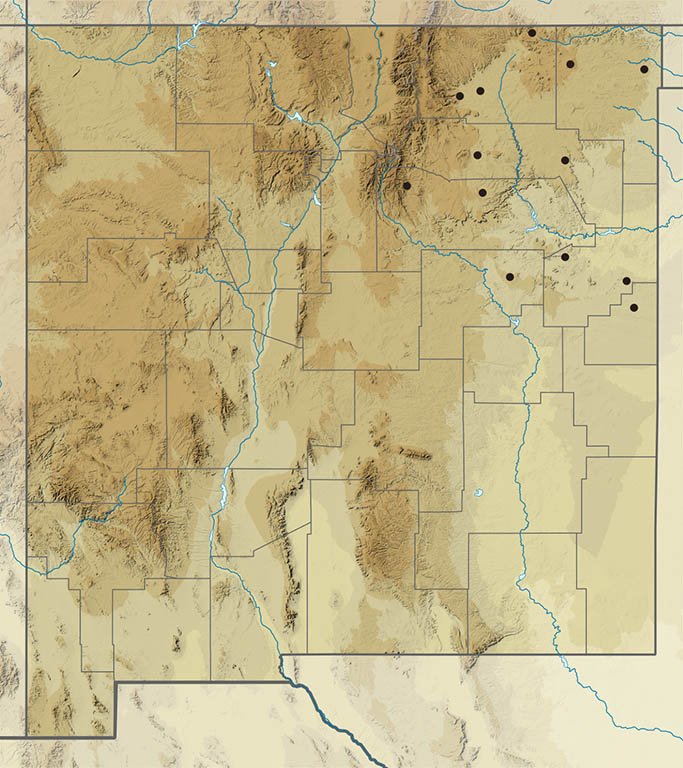

Description. On Olympia, the forewing apical black marks are reduced compared to sister species. Yellow-green underside marbling occurs in slender, loose arcs. Antennae are solid white. The ventral hindwing has a rosy blush on freshly emerged specimens. Range and Habitat. Euchloe olympia is headquartered in the Great Plains. Its southwest limit includes northeast New Mexico’s high plains up to the foothills of the Sangre de Cristos (counties: Co,Cu,Gu,Ha,Mo,Qu,SM,Un). It lives in canyon and mesa country populated by shortgrass prairie, oak, juniper and piñon pine (4500 to 8500′). Life History. Mustards (Brassicaceae) host Euchloe olympia. New Mexico hosts include Arabis glabra, Descurainia pinnata, D. richardsonii, D. sophia, Lepidium campestra, and L. virginicum. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Like its congeners, Olympia is a univoltine, early spring flyer. New Mexico records span April 1 to June 9, favoring the earlier dates. Individual adults may live only one week. Adults are often found near treeless ridge tops or grassy mesa tops, tacking patiently across open expanses seeking potential mates. Flight is more aggressive in the presence of other spring hilltoppers such as Sisynbria sisymbrii. Comments. Our populations here at the southwest edge of its range arguably belong to subspecies Euchloe olympia rosa (W. H. Edwards). In the early 1980s, your humble author saw a map of the then known distribution of Olympia, which included southeast Colorado, western Oklahoma and Northwest Texas panhandle, but not adjacent New Mexico. I finally tracked it down on 30 April 1988, northeast of Clayton.

Euchloe lotta Beutenmiller 1898 Desert Marble (updated May 11, 2023)

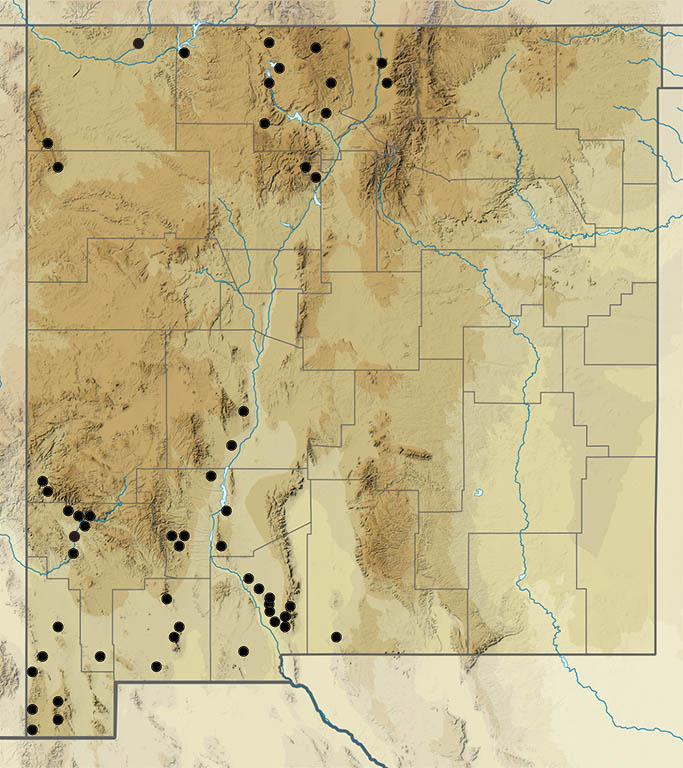

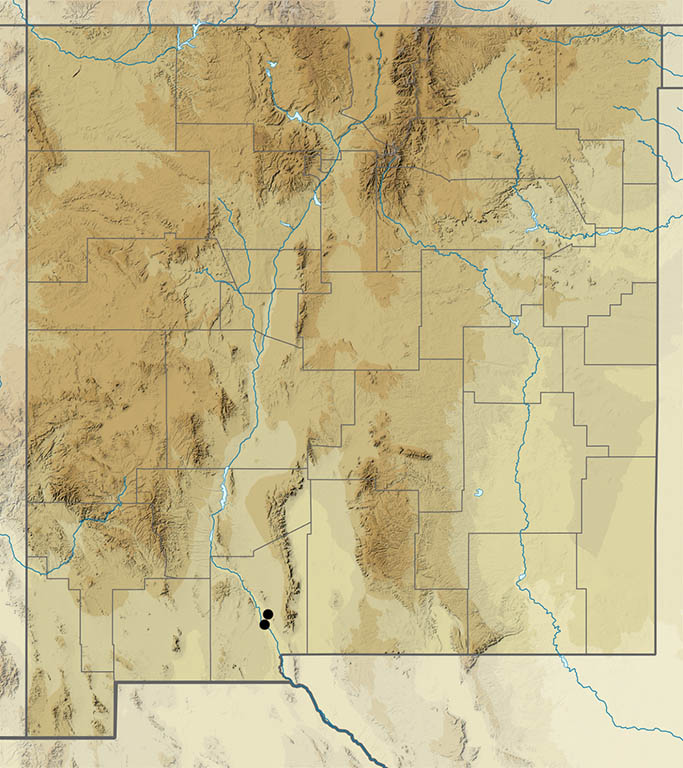

Description. Underside marbling on Desert Marble is darker and more invaded by the white ground color that in congeners. Compared to the Large Marble, the forewing cell-end bar is broader and forewing apical marks are faded. Range and Habitat. Euchloe lotta is an Upper Sonoran and Transition Zone insect. It occurs from British Columbia south through the Great Basin into Mexico. In New Mexico it lives in the northwest quadrant (counties: LA,MK,RA,Sv,SJ,Ta), 6000 to 9000’, and the southwest quadrant (counties: Ca,DA,Gr,Hi,Li,Lu,Ot,Si,So), 4100 to 7000′. Life History. Desert Marble larvae eat a variety of mustards (Brassicaceae), in the genera: Boechera (formerly Arabis), Caulanthus, Isatis, Descurainia, Dryopetalon, Guillenia, Lepidium, Sisymbrium, Stanleya, Streptanthus, Streptanthella and Thelypodium. Eggs hatch quickly, then larvae feed and pupate quickly; pupae overwinter. Flight. Euchloe lotta flies promptly in spring, when males defend hilltop territories alongside orangetips and Spring Whites. Records for southwest New Mexico begin February 24 and end May 8, peaking in April. Records for northwest New Mexico span April 11 to June 4, peaking in May. Comments. Our populations formerly had been placed as a subspecies of Euchloe hyantis (W. H. Edwards, 1871), a species now understood to be limited to the Pacific Coast and adjacent areas in California, Oregon and extreme western Arizona.

Glutophrissa drusilla (Cramer, 1777) Florida White (updated January 10, 2024)

Description. Florida White is one of three large, subtropical whites that rarely stray into New Mexico. Male Florida Whites are almost immaculate white above and below. Females have a black forewing outer margin and a yellow cast to the hindwing above. It is larger than European Cabbage White; average wingspan is 55mm but exceptional individuals can measure up to 77 mm. Range and Habitat. This is truly a tropical species whose home base includes Mexico, Central America, tropical South America, and the southern tip of Florida. Adults do wander widely, however, and are recorded from the interior US with surprising frequency. Wanderers are hungry, so look for them at nectar. Life History. Larval hosts are members of the pepper family (Capparidaceae), but there is no evidence of reproduction in our state. Flight. Florida White has been confirmed only twice in New Mexico. Dr. Dale A. Zimmerman gets credit for our only catch, on 24 June 1971 in Silver City (Gr). Almost precisely 50 years later, Rob Wu photographed a female nectaring in the Pollinator Garden at White Sands Missile Range (DA) on July 29, 2021. She was in remarkably good condition considering how far she likely traveled. In New Mexico, this species is “least unlikely” during the summer monsoons, when many subtropical species are diffusing northward, unaware of the coming winter. Farther south, where it is resident, expect it any time of year. Comments. This butterfly was formerly in the genus Appias Hübner.

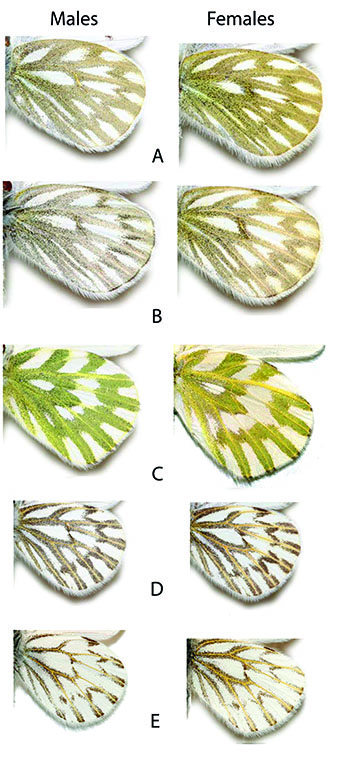

Neophasia menapia (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1859) Pine White (updated March 10, 2022)

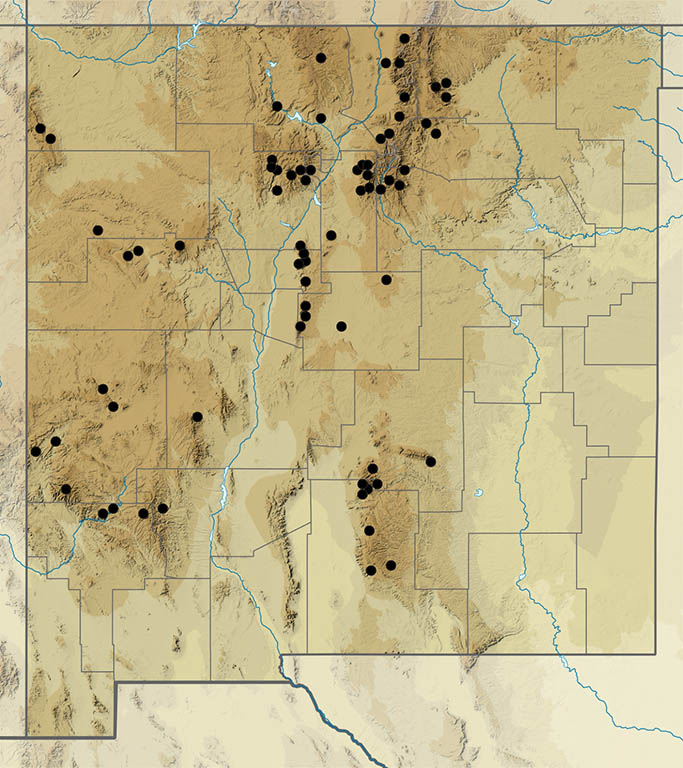

Description. Pine Whites are indeed white, accented by black marks at the forewing apex and a black bar at the end of the forewing cell. Beneath, the hindwing is white with gray/black scaling on the veins, which can be quite heavy in females. Females have the hindwing margin strongly edged or outlined in red; that red edging is thin and weak in males. Range and Habitat. Pine Whites inhabit mountains of western North America, including pine forests of major New Mexico mountains (counties: Be,Ca,Ci,Co,Gr,Li,LA,MK,Mo,Ot,RA,Sv,SJ,SM,SF,Si,So,Ta,To), generally 6500 to 10,000′ altitude. Life History. Larvae of Neophasia species eat developing pine needles. Neophasia menapia can utilize a variety of pine species. Pinus ponderosa (Pinaceae) is preferred in New Mexico, though Pinus edulis (piñon, or nut pine) is a distant second choice. Eggs overwinter. Flight. Pine Whites fly in one annual summer brood from June 29 to September 26, peaking in July. Their flight appears weak, yet males often soar high in the pines, beyond reach of nets and cameras. Both sexes seek nectar nearer the ground. Comments. Our oldest report is from University of Kansas Co-Founder and Professor Francis Huntington Snow, who captured it in Gallinas Canyon near Las Vegas (SM) in 1882. Few named subspecies of menapia seem worthy of recognition, but ours can be placed with Neophasia menapia magnamenapia Austin, 1998.

Neophasia terlooii Behr, 1869 Chiricahua White (updated March 10, 2022)

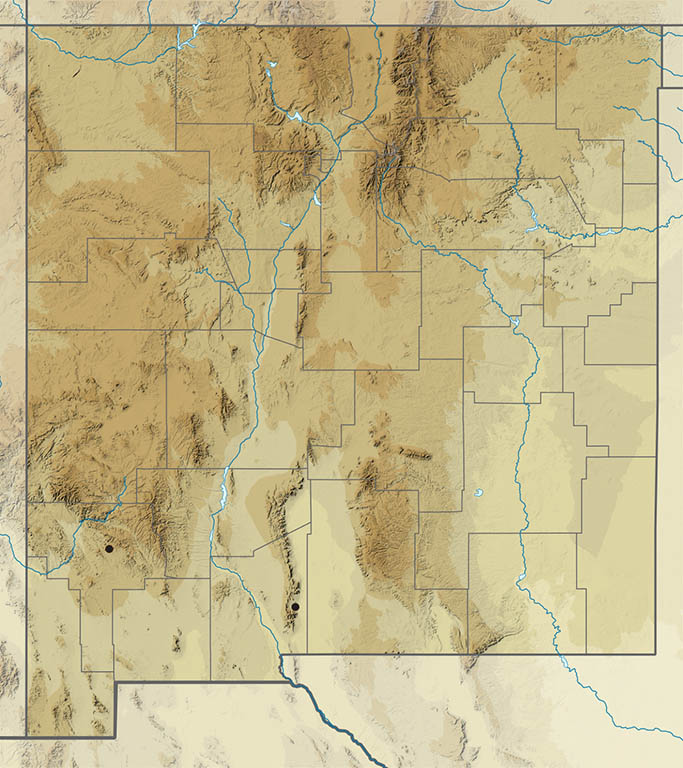

Description. Neophasia terlooii is one of our most sexually dimorphic species. Males resemble Pine Whites, but with an entirely black forewing cell on the upperside. Strikingly orange females have black veins and margins, resembling a miniature Monarch. Range and Habitat. Chiricahua Whites inhabit pine forests in the Mexican Sierra Madre and north as far as the high peaks of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. Our few reports are from above 6500′ elevation in the Animas and Peloncillo Mountains (counties: Hi). Life History. Larvae eat developing needles of Pinus ponderosa, Pinus engelmannii and Pinus cembroides. Flight. Neophasia terlooii is double-brooded with adults in flight during mid-summer and again in autumn, sometimes into November; our few reports are for June and September. Males float in and out of the pine canopy, descending for nectar and to investigate orange objects, hoping for females. Comments. New Mexico populations are in remote areas. Our lack of data could represent infrequent visits by observers, or we may have impermanent colonies that are peripheral and not always occupied.

Ascia monuste (Linnaeus, 1764) Great Southern White (updated January 12, 2024)

Description. The subtropical Great Southern White is a little larger than Florida White, but a tad smaller than Giant White, as it should be (wingspan: 6.3 – 8.6 cm). Dark marks decorate the forewing apex and, in females, extend inward along the veins. Females may have a black cell spot. There are vein-end dark marks on the hindwing upperside. Antennal knobs are turquoise. Range and habitat. Great Southern Whites breed year-round in the Neotropics as far north as south Florida and south Texas. Life history. Larval hosts are from the Brassicaceae, Capparidaceae, Bataceae, Liliaceae, and Tropaeolaceae. Hungry adults will come to nectar. Flight. Adults are good fliers and wander widely, resulting in accidental strays as far as the north-central US. Strays are unlikely anywhere, including in New Mexico, but the odds increase during and after a strong monsoon season. Comments. Few sightings have been recorded from New Mexico and all were in the Las Cruces area. Our first was from Las Cruces on October 15, 1973; the specimen is at NMSU. More recently, 2021 was our best year ever for Ascia monuste because CJ Goin photographed a worn male at Mesilla Dam on September 6, 2021, and Meg Freyermuth photographed another in her backyard on October 10, 2021. One can only imagine how many more went unnoticed in far southern New Mexico that autumn.

Ganyra josephina (Godart, 1819) Giant White (updated March 10, 2022)

Description. Giant White is the largest of the subtropical Pierines that have strayed to New Mexico. Males are pure white with a black spot in the forewing cell. Females are similar, but with dark accents on the veins toward the wing margins. Antennal knobs are turquoise, as with Great Southern White. Range and habitat. This species is resident in the Caribbean islands and in Central America, breeding as far north as south Texas. Other North American sightings are accidental strays. Life history. Woody Capparidaceae (peppers) serve as larval hosts for Ganyra josephina, but we have none in New Mexico and thus no reproduction can be anticipated here. Giant Whites go through several generations per year in the tropics. Flight. Adults will come to nectar at urban gardens. Comments. There is one report from New Mexico, a sight record from Albuquerque (Be) by Michael E. Toliver at his former home.

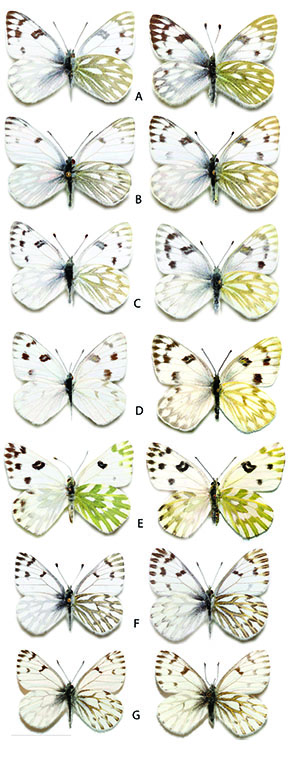

Comparing the species of ‘Checkered Whites’ found in New Mexico.

Sisymbria sisymbrii (Boisduval, 1852) Spring White (updated January 12, 2024)

Description. Spring Whites are average size for whites, with wingspans of about 1.5 inches. They show black forewing apical marks on the veins and a small black bar in the cell. The hindwing underside has green scales painted alongside the veins, which also may be scaled with yellow when fresh out of the chrysalis. Range and Habitat. This western North American species ranges from the Yukon south to northwest Mexico through most of montane western US. In New Mexico it lives in Upper Sonoran to Transition Zone savannas extending onto our eastern foothills (all counties except Cu,DB,Gu,Le,Ro), 4800 to 8400′. Life History. Many native mustards (Brassicaceae) are larval hosts. Bailowitz and Brock (2021) listed the genera Boechera (formerly Arabis), Dryopetalon, Thysanocarpis, Descurainia and Thelypodiopsis. Scott (1986) gave Caulanthus, Sisymbrium and Streptanthus as hosts. A mature larva was seen on Hesperidanthus (formerly Schoenocrambe) linearifolia, June 3, 2019, south of Santa Fe. Pupae overwinter. Flight. One of the first butterflies to fly in spring, records extend from December 21 to June 8. Males are moderate hilltoppers. Both sexes seek nectar. Comments. Populations in most of New Mexico fit the above description and are subspecies Sisymbria sisymbrii elivata W. Barnes & Benjamin 1926. In Bootheel (Hi) populations, scaling on the ventral hindwing veins is reduced to postmedian chevrons; this is subspecies Sisymbria sisymbrii transversa R. Holland 1995. Grishin, in Zhang, et. al. (2021) described Sisymbria as a subgenus of Pontia but noted “… strong genetic diversification behind this apparent phenotypic similarity [within Pontia] may suggest elevating subgenera of Pontia to genera … a step that we refrain from.” Pelham (2022) took that step and so do we.

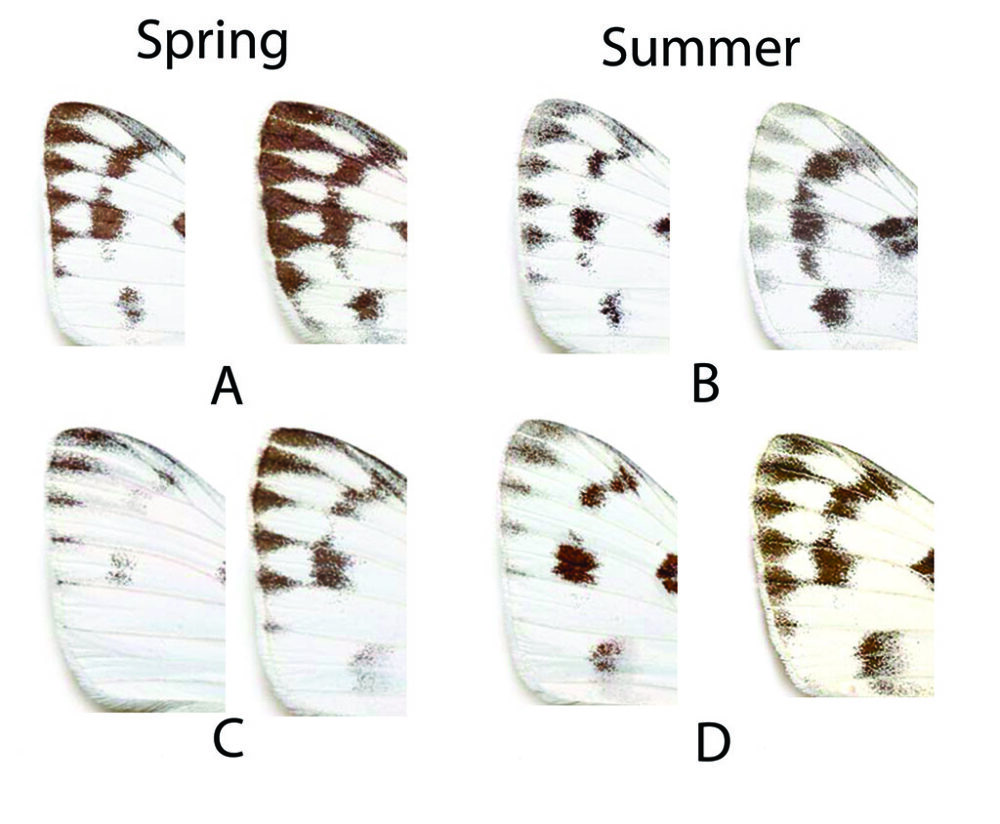

Pontia protodice (Boisduval & Le Conte [1830]) Checkered White (updated March 10, 2022)

Description. Male Checkered Whites are mostly white with black marks at the forewing apex, a loose band of dashes and a rectangular spot in the forewing cell. Beneath, the male hindwing is often immaculate but may have gray chevrons. Females have rather heavier markings. The ventral hindwing has gray scales along the veins plus marginal and submarginal chevrons. Spring forms are more heavily marked in both sexes, resembling P. occidentalis. The submarginal spots on the dorsal forewing of protodice are separate, whereas in occidentalis they form a connected arch. Range and Habitat. One of the most common and widespread butterflies in New Mexico, Pontia protodice breeds from California east to Virginia and south into Mexico, straying north to Canada. In New Mexico it lives in deserts, prairies and open woodlands (all counties) up to 11,500′. Life History. Larvae eat most native mustard species (Brassicaceae), including Arabis drummondii, Schoenocrambe linearifolia, Wislizenia refracta, Lepidium densiflorum and Thelypodiopsis linearifolia. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Checkered Whites are continuously brooded where growing conditions permit. Statewide, our records span January 5 to December 30. Males often seek hilltops in the spring; both sexes come to flowers. Comments. Cold weather pupae produce form vernalis, which is more heavily marked on the underside and resembles Pontia occidentalis. Hira Walker’s photo below shows the rarely observed phenomenon of pupal mating, in which a male stands guard over a female pupa, then initiates copulation while she ecloses.

Pontia occidentalis (Reakirt, 1866) Western White (updated March 10, 2022)

Description. Very similar to Checkered Whites, Western Whites have upperside forewing postmedian spots connected in an arc and veins are penciled with black. Gray-green scales are painted broadly along the ventral hindwing veins, much like cold season Checkered, which poses the greatest difficulty; the forewing postmedian spots seem to offer the best cue. Range and Habitat. Pontia occidentalis lives from the southern Rockies and the Sierra Nevada north into Canada and Alaska. In New Mexico, it seems to be present in the high plains and in Hudsonian Zone areas above treeline (counties: Co,Gu,SM,Ta,Un). Life History. Scott (1992) gave Descurainia richardsonii and Rorippa teres (Brassicaceae) as hosts. “Last July, in Las Vegas, N. M., my little son Martin, found a number of larvae which I took to be those of Pieris protodice, living upon Cleome serrulata [Rocky Mountain bee plant; Capparidaceae]. As the food-plant was a new one I requested him to rear the butterflies . . . when they emerged . . . they were . . . occidentalis” Cockerell (1901a). Flight. This species is bivoltine. A spring generation flies from March to April; the summer brood from July to August. Males hilltop. Comments. Confusion is possible with Pontia protodice, particularly with the latter’s heavily marked spring form vernalis. Butterflyers seeking Western Whites in New Mexico are routinely frustrated not just by the inaccessibility of their known habitat, but also by the superabundance and ubiquity of the similar Checkered White. Then there are the identification challenges, about which has been said: “current knowledge doesn’t allow separation of many/most individuals” (Glassberg 2017: 38). Your best chance is to get multiple dorsal and ventral photos of individuals in good or better condition, so you can inspect all potential diagnostic marks.

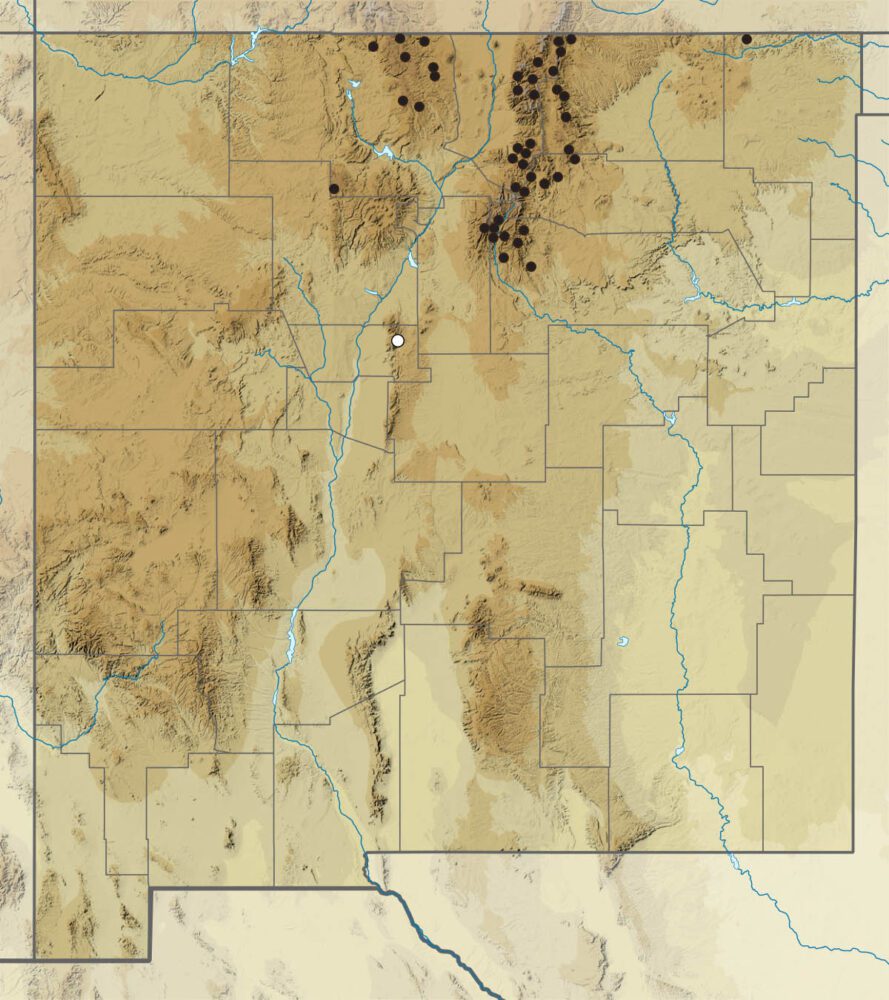

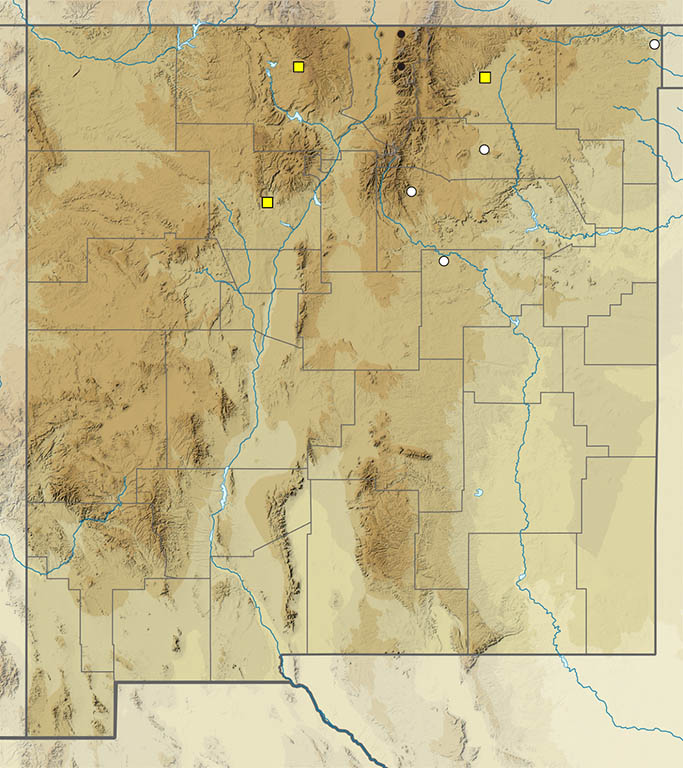

Pontieuchloia beckerii (W. H. Edwards, 1871) Becker’s White (updated May 20, 2024)

Description. Resemblance of Becker’s White to ubiquitous Checkered White causes some confusion about the extent of this species in New Mexico. Becker’s is white with black dorsal forewing apical marks. A squarish spot in the forewing cell is noticeably bolder and blacker than in Pontia protodice. Ventral hindwings have more extensive green scaling along the veins. Range and Habitat. Becker’s White is a Great Basin insect distributed from Baja California north to British Columbia and east across the Great Basin to the central Colorado Rockies. It occupies shrubby hillsides and arroyos. In New Mexico it occupies our northwest quadrant, but it also occurs near Raton (counties: Co,MK?,RA,SJ), 5000 to 6800′. Life History. Mustards (Brassicaceae) are larval hosts. Scott (1986) listed species in the genera Isomeris, Stanleya, Arabis, Brassica, Sisymbrium, Lepidium, Descurainia and Thelypodium. Winter is passed as a chrysalis. Flight. The spring flight extends from at least April 28 to May 18. There also are southern Colorado records from July 22 to September 14, indicating a late summer brood. Adults seek nectar in open areas and drainage bottoms. Comments. Many more observations in northwest New Mexico are needed to fill out our limited knowledge of this insect in our state. Grishin, in Zhang, et. al. (2021), described Pontieuchloia as a subgenus, with the same rationale they used to separate Sisymbria from Pontia as a subgenus. With similar reasoning, Pelham (2022) raised Pontieuchloia to generic status, which we follow here.

Pieris rapae (Linnaeus, 1758) European Cabbage White (updated March 10, 2022)

Description. As you probably already know from experience, Cabbage White has a black dorsal forewing tip, a gray-green ventral hindwing, one (males) or two (females) black spots on the forewing above, and a deceptively tumbling flight. An unmarked form ”immaculata” lacks most of the makings of the typical form and could be confused with Pieris marginalis. However, that form lacks any indication of markings on the veins of the ventral hind wing. Range and Habitat. The European Cabbage White has invaded all of temperate North America and, though not as successful as in the eastern US, it is scattered in human communities throughout New Mexico (all counties but MK?). Pieris rapae occupies disturbed (that is, human) habitats that are routinely found in urbanized, suburban or agricultural areas. Life History. Vegetable and ornamental gardeners know the life cycle of this butterfly only too well. Larvae eat foliage of cabbage, broccoli and other alien (non-native) species of Brassicaceae. Pupae overwinter. Flight. Adults emerge in spring and produce successive broods until winter cold. New Mexico records span January 5 to December 19 and suggest two or three broods depending on local growing season length. Adults fly near the host and come to nectar. Comments. This species is not native to North America, and it is the only such exotic butterfly species that has made a home in New Mexico. “No other butterfly is so successful over such a great variety and expanse of landscape” (Robert Michael Pyle). In New Mexico, human communities that thrived in the past, but are now uninhabited ghost towns, still retain surviving exotic Brassicaceae dating back to miners’ vegetable gardens and Cabbage Whites still fly there, having persisted where humans did not.

Pieris marginalis Scudder 1861 Margined White (updated April 18, 2023)

Description. Margined Whites resemble European Cabbage Whites, being white above with a dark forewing apex. Undersides, however, are creamy white with gray scaling on hindwing veins. Females may have dark scales on upperside hindwing veins as well. Scaling of VHW veins tends to be heavier in spring individuals and lighter in summer individuals. The old name, ‘Veined’ White, seems more appropriate than ‘Margined’ White. Range and Habitat. Pieris marginalis lives across boreal North America from Alaska to Labrador. It also occurs south in the Rocky Mountains to New Mexico, where it flies along riparian corridors in our higher mountain settings (counties: Be,Ca,Co,LA,Li,MK?,Mo,Ot,RA,Sv,SM,SF,Ta), 7500 to 11,000′. Life History. Scott (1986) listed many host genera among the native mustards (Brassicaceae). One female oviposited on Cardamine cordifolia along the South Fork Rio Bonito (Li) on 19 April 2002 (S. Cary). Flight. Overwintering chrysalids divulge adults in spring. Flight peaks occur from April to June and again in July and August, with a partial third brood in September. Extreme dates are April 9 and September 12. Adults fly near the ground in sunny openings, often visiting nectar and damp sand. Comments. This butterfly is placed by some taxonomists with Old World Pieris napi (Linneaus). Most workers now consider New World populations to comprise multiple species, none of which is Pieris napi. North-central New Mexico has Rocky Mountains subspecies Pieris marginalis mcdunnoughii W. Barnes & McDunnough 1916. Populations in the Mogollon Mountains (Ca) are Pieris marginalis mogollon Burdick 1942. Populations in the Sacramento Mountains (Li,Ot) are the newly described Pieris marginalis siblanca Grishin 2022.

‘Sierra Blanca’ Margined White spring form (Pieris marginalis siblanca) Bonito Creek, Lincoln National Forest, Lincoln Co., NM; April 17, 2023 (photo by Marta Reece)