© Steven J. Cary, April 22 2024

This month, our featured piece takes another bite out of New Mexico Celastrina by demonstrating that Southwestern Azure (cinerea) belongs with Mexican Azure (Celastrina gozora) rather than Echo Azure (Celastrina echo). But first, I invite you to peruse a couple of brief but important announcements and then a wonderful surprise out of Portales.

A Natural History of The Odonata of Doña Ana County with Notes on the Black Range is now available as a free download from the Black Range Website here: Odonata | The Black Range. Per Bob Barnes, “the principal photographer and author of this work is James Von Loh. His photography, and that of Gordon Berman and others, is beautiful and informative. Jim’s narrative provides wonderful insights into the natural history of the Odonata of our area.”

Selvi Viswanathan has a terrific article with photos in NABA’s Butterfly Gardening Magazine volume 29, issue 1, Spring 2024. Please look into it!

Our second annual Python Skipper/Margarita Skipper Challenge resumes in May. If you would like to help out this year, please reach out to Steve at sjcary1@outlook.com.

A state record butterfly for New Mexico discovered thirty-five years after its collection, by Anisha Sapkota. I’m from Nepal, a small, beautiful country in the lap of the Himalayas. I have spent my whole life in the sub-tropics with greenery everywhere; thus, when I came to New Mexico for my master’s degree at Eastern New Mexico University (ENMU), Portales, where it is very dry and flat, it wasn’t a very pleasant experience. I used to call home and say that I was on Mars, haha. But soon, when I started going out to explore for butterflies, I found that this part of New Mexico is in fact a neglected gem. Every butterfly I saw was, of course, new; they were very different from what I was used to seeing in Nepal. I was so intrigued by the butterfly diversity in eastern New Mexico that I decided to do my master’s thesis on the exploration of butterflies there. The Natural History Museum at ENMU, Portales, has a small but very good collection of butterflies. I started to study the specimens in the collection to get a general idea of what I could see during butterfly surveys. While working on the collection, I tried arranging butterflies by their family, and then I tried arranging butterflies by morphological similarity. Each butterfly had at least a pair; sometimes there were many specimens of a single species, for example, the Monarch. There was this nymphalid that had no other similar-looking specimens in the collection. At that time, I was still in the phase of learning the general identification of butterflies found in the US, so I was unable to identify the nymphalid.

Months later, in December 2022, while me and my partner, Sajan, were butterflying at the National Butterfly Center in Mission, TX, we saw an Unidentified Flying Object (UFO). The UFO turned out to be the Orion Cecropian, a very rare stray from Mexico. It was sitting on a banana bait log, and everyone was surrounding it as if it were a celebrity (well, it was indeed!). The Cecropian was very photogenic. Everyone was calling their partners, and people were running from one point to the next to see the butterfly. It felt like a festival. This event triggered Sajan, and he remembered that the unidentified specimen we had in the collection looked like Orion Cecropian! We came back to the university and compared the photo of Orion Cecropian with the unidentified specimen. Some features matched, but something was still off; the underwing pattern was different, and the specimen had a tail. This led me to search for ‘Tailed Cecropian’ on the internet, and bingo! the specimen was a Tailed Cecropian. The usual range of Tailed Cecropian extends from Mexico to Brazil, but strays had been recorded in Arizona and Texas a few times; however, never from New Mexico. This makes it a state record for New Mexico! I have published this finding in the recent issue of Southwestern Entomologist. Here’s the link: https://doi.org/10.3958/059.049.0142. And guess what the title is? The article is titled ‘Historis acheronta, A New Mexico New Butterfly Record Hidden in a Cabinet of a Natural History Museum’. And the coolest thing is that this specimen was collected by N. Jorgensen in 1986, about 35 years ago, from Portales itself.

and now our featured story . . .

Disclosure of Southwestern Azure, Celastrina gozora cinerea, in New Mexico, by Steve Cary, Andy Warren and Mike Toliver. Introduction. The azures (Celastrina spp.) have long been a tough group to make complete taxonomic sense of. A few species stand out as unique, but several of North America’s ten or so azure species look very much like other azure species. Ventral marks are largely the same among most azures, usually varying only in intensity of development, both within species and between species. Uppersides can be more informative, but photographers don’t usually get a view of that and so, like the lead author, struggle to make sense of New Mexico’s azures.

As noted in last month’s post, more decisive information can be gleaned from properly curated specimens. An excellent assortment of New Mexico azures resides at the C. P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity at Colorado State University (CSU) in Fort Collins. Over the past several weeks, Andy generously spent time there, went through their ~500 western azure specimens, and took photos (dorsal and ventral) of New Mexico specimens where needed. Much of the discussion that follows in this post hinges on Andy’s work with those CSU specimens and with relevant Celastrina specimens from his personal collection.

For this post, we are focusing on the entity called cinerea (W. H. Edwards 1883, TL = Arizona) which merits the English name Southwestern Azure. From a nomenclature standpoint, this butterfly has for the last few years resided in Jonathan Pelham’s (2023) catalogue as a subspecies of Echo Azure: Celastrina echo cinerea. While that placement may have made sense at one time, Jonathan himself considered it tentative and we did not find any published documentation to support such a relationship between echo and cinerea. Moreover, the collective wisdom today seems to restrict C. echo (W. H. Edwards 1864) to the West Coast and to interior areas well west of New Mexico (though possibly entering northwest Colorado). If all that is true, then what is the azure we have in most of New Mexico?

After examining hundreds of specimens and associated label data, as well as southwestern and Mexican Celastrina on iNaturalist, we now think Southwestern Azure (cinerea) fits comfortably under Mexican Azure = Celastrina gozora (Boisduval 1870), with cinerea being the northernmost and bluest expression of gozora. For nomenclature purposes, we recommend use of the epithet Celastrina gozora cinerea, a new combination. Decades ago, Richard Holland considered some of his New Mexico azure specimens to be good fits for gozora and listed them as such in Toliver et al. (2001: 280). Ironically, he seems to have had it right all along.

Southwestern Azure. The azure of interest today is the one featured in the adjacent photo. It is widespread across most of New Mexico and is resident in most counties, especially those with cool, moist uplands and south of I-40. Many of us are familiar with it, but we all need help knowing what to call it. A couple decades ago, we called it Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon). Upon publication of Pelham’s Catalogue in 2008, we switched to calling it Echo Azure (Celastrina echo) subspecies cinerea. That subspecific epithet is appropriate, but as we explain below, it fits best as a subspecies of Mexican Azure (Celastrina gozora).

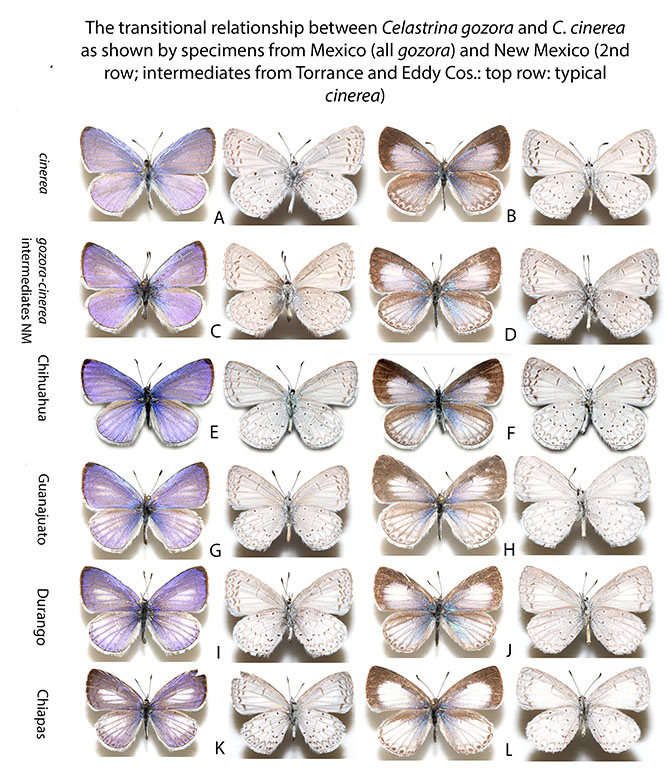

The notion that cinerea belongs with gozora (Mexican Azure) is supported by their closely related phenotypes. In the plate below (Figure 2), cinerea is at the top because north is up. But let us begin at the bottom, in Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas, where gozora is the resident azure. The whitest gozora occur in Chiapas and south into Central America. Observe the dearth of blue; the female has only a splash at the dorsal wing bases; on the male, large white areas dominate the forewing and the hindwing.

From C. gozora on the bottom row of Fig. 1, let’s hopscotch our way generally north through Mexico’s diverse network of biotic provinces and ecoregions and thus upward through Mike T.’s beautiful plate. Examples of Mexican Azures from Durango and Guanajuato show progressively more dorsal blue on males and females. Adjacent to the US, Chihuahua has azure females that are bluer still, while males are dominantly blue but with a whitish cast. Based on specimens examined and iNaturalist observations, the dorsally bluest cinerea occupy southwest Colorado, southern and central Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Trans-Pecos Texas. Some males and females in southeast New Mexico and Trans-Pecos Texas show evidence of gozora traits, such as the ghostly pale median pane on male dorsal forewing (also see Figure 3) and increased white areas on the dorsal forewing and hindwing of females (also see Figure 4), as seen above.

Ventral surfaces of both sexes, all the way from Chiapas to New Mexico, exhibit a simple and consistent underside which includes a very fine-grained and pale gray ground color. Against that clean, linen, ventral tablecloth (please hang with us on this odd analogy) is placed a pretty standard setting of Celastrina dashes, dots and chevrons. Submarginal triangles, like napkins folded on the diagonal, are present but never heavy or dark. Hindwing basal and median dots also are not heavy and are encircled by white rings, kind of like (here’s our table setting analogy), small cups of weak tea on larger white saucers on that linen tablecloth. Wing fringes are white and very lightly checkered: checkering is mostly absent on the hindwing but often occurs on the forewing as dark vein-end lines. As we will see in a subsequent post, ventral marks on cinerea are usually pale in comparison to those on sidara (Clench 1944), and ventral dark splotchiness that may be normal for lumarco Scott 2006 is absent in cinerea as far as we know.

Voltinism. Most azures (Celastrina spp.) are single-brooded or univoltine, completing one generation per year with adults flying in spring to early summer. Southwestern (cinerea) and Mexican Azure (gozora) are multiple-brooded and this is additional evidence they are the same species. They complete as many generations per year as the local growing season and larval foodplant resources will support. Andy has seen gozora from all over Mexico, where adults can be found all months of the year, and there do not seem to be well-defined broods or flights. Regarding cinerea in Arizona, Bailowitz and Brock (2021) stated as follows: “At lower elevations, most . . . azure records are from winter and spring. Above the desert floor, records exist in the warmer months. Together, the species is on the wing throughout the year.”

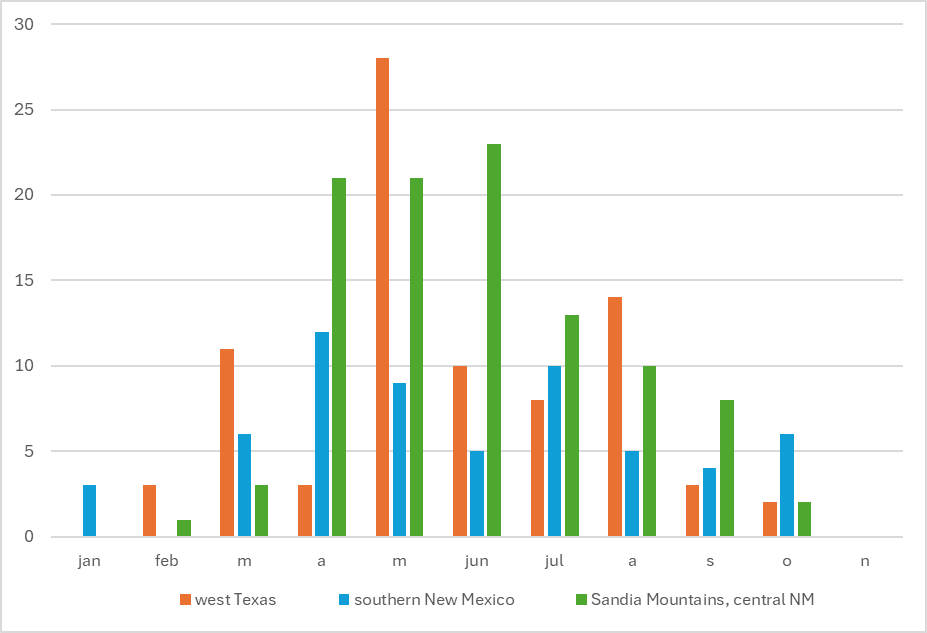

Notwithstanding the inevitable sampling bias inherent in the above chart, it is evident that in southern New Mexico and west Texas, cinerea has been recorded in every month of the year except November and December. Those data suggest as many as three flight peaks and three or more overlapping generations per year. Farther north in a shorter growing season, cinerea shows two broadly overlapping flights in the Albuquerque area. Southwestern Azure has a reliable second (summer) generation even in northern New Mexico, where high elevations further restrict the growing season. In contrast, Echo Azure does have a second (summer) generation locally in California, but it does not in Washington, Oregon, Idaho or Utah, and nowhere are they potentially continuously brooded or multi-brooded, as cinerea and gozora seem to be.

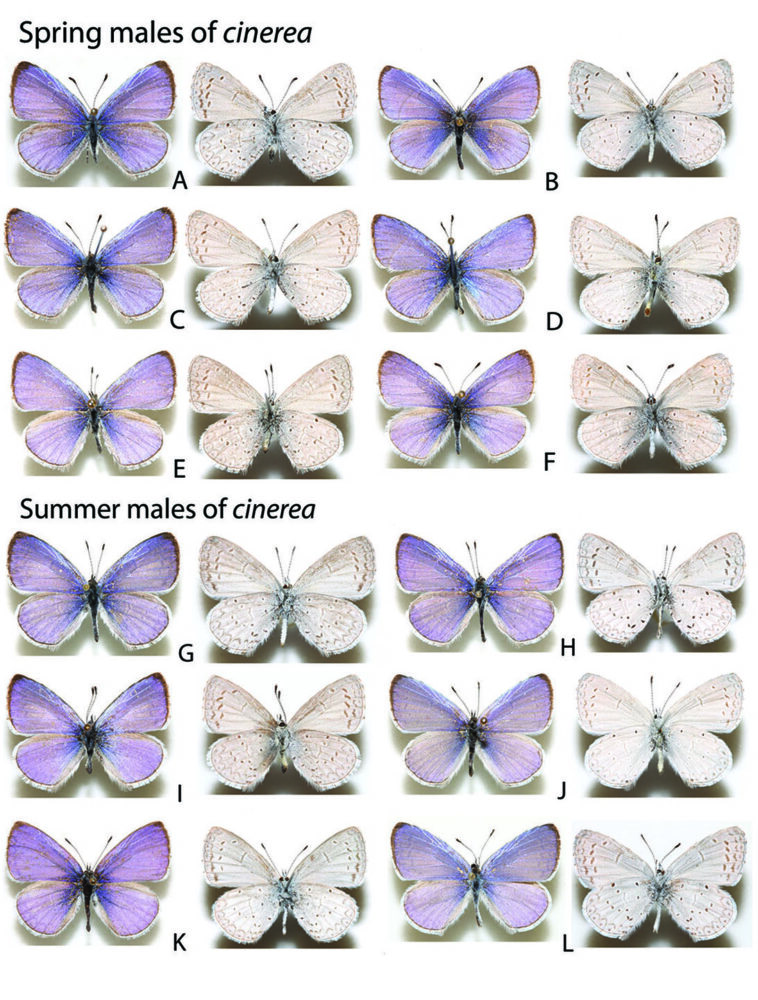

Seasonal Dimorphism. We still had work to do because we could see phenotypic variation among cinerea females that was not explained by this new species assignment for cinerea. Two or more generations per year create opportunities for cool season adults to look different from warm season adults. This phenomenon is well documented in many bivoltine butterfly species in North America. It had not been previously documented for cinerea, but the specimens we examined, especially the females, leave no doubt that cinerea is seasonally dimorphic in New Mexico and west Texas. The plate below (Figure 4) uses six spring males and six summer males to show there is little seasonal difference among cinerea males: they are bright blue above with the standard ventral cinerea table-setting. However, the spring cinerea males do seem to average somewhat deeper blue above than the slightly paler summer males.

Summer variation in Celastrina gozora cinerea males (all photos by Andy Warren – dorsal on left, ventral on right): G). TX, Culberson Co., Guadalupe Mts. NP, Bowl, 8000′, 7 Jul 1986 RWH (CSU). H). NM, Sierra Co., E slope Black Range, 7 mi up FS 157 from NM 151, 18 Jun 1988 RWH (CSU). I). NM, Torrance Co. Manzano Mts., 1 mi W of Pine Shadow Spring, 8000′, 30 May 1968 RWH (CSU). J). NM, Socorro Co., Ladron Peak, Cyn. del Alamito, 6100′, 1 Oct 1968 RWH (CSU). K). NM, Sandoval Co., 7 mi NNE of Ponderosa, 7380′, 6 Sep 1969 RES (CSU). L). NM, San Juan Co., Chuska Mts., Whiskey Creek, 1.8 mi E of N-12, 7000′, 5 Aug 1978 RWH (CSU).

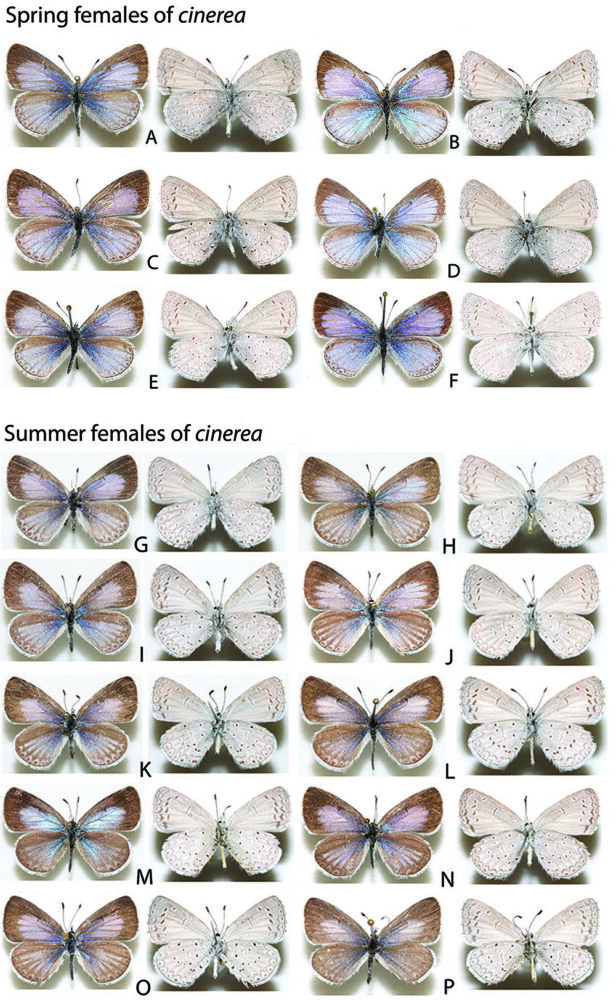

Females, on the other hand, vary quite a bit between spring and summer (see Figure 5 below). Six first generation females from February, March, and April are consistently much bluer above than what is seen in subsequent generations. Part of that extra blue can be traced to the forewing basal and median blue region, being larger in spring and leaving less room for the black margin, which is reduced accordingly. Summer females were sufficiently variable that we show ten individuals to cover the range of variation. Overall, the black margin is enlarged and the median blue reduced compared to spring females. Dorsal hindwings of spring females also are more blue than black, but on summer females the blue scaling is mostly limited to the hindwing veins, with black expanding to make up the difference. The ventral “table-setting” on spring females and spring males seems to be a tad weaker, the marks fainter or washed out as compared to that of summer females, which is more firmly punctuated with the standard marks, some approaching sidara in appearance.

Summer variation in female Celastrina gozora cinerea (all photos by Andy Warren – dorsal on left, ventral on right): G). NM, McKinley Co., Zuni Mts., microwave relay site, 2 mi S of Ft. Wingate, 7000′, 30 Sep 1978 RWH (CSU). H). NM, McKinley Co., Zuni Mts., Nutria Diversion Res., Tampico Cyn., 18 Jun 1977 RWH (CSU). I). NM, Hidalgo Co., W slope Animas Mts., Black Bill Spr., 6000′, 8 Oct 1993 RWH (CSU). J). NM, Dona Ana Co., E slope Organ Mts., 2 mi N of Aguirre Spr., 5000′, 6 May 1979 RWH (CSU). K). NM, Dona Ana Co., W slope Organ Mts., Fillmore Cyn., 6000′, 23 Sep 1979 RWH (CSU). L). NM, Grant-Sierra Co., Emory Pass, 8228′, 5 Aug 1986 RES (CSU). M). NM, McKinley Co., Zuni Mts., Diener Cyn., Mirabel Mine, 8000′, 1 Aug 1976, RWH (CSU). N). NM, Socorro Co., Ladron Peak, Cyn. del Alamito, 6500′, 20 Jun 1968 RWH (CSU). O). NM, Luna Co., SE slope Cooke’s Peak, BLM office at Ft. Seldon, 5000′, 25 Jun 1995 WRH, ESC & SJC (CSU). P). NM, Grant Co., Gila NF, Copperas Spring, Copperas Ck., 7000′, Hwy. 15, mi. 29.6, 16 Jul 1980, J. S. Nordin (CSU).

Because most Celastrina species are univoltine, seasonal dimorphism in cinerea came as a surprise to all three of us. Clearly cinerea is seasonally dimorphic and indeed why would it not be? We understand that in the east, Celastrina neglecta also may exhibit seasonal dimorphism, so the phenomenon in cinerea is not unexpected.

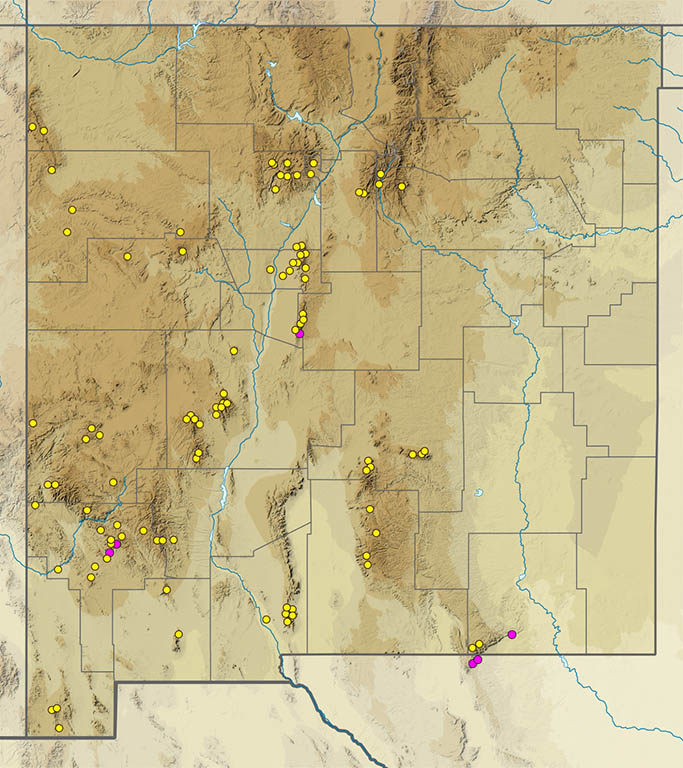

Eastern and northern distribution limits of cinerea seem to be in west Texas, eastern New Mexico, southernmost Colorado, and central and southern Utah. Thus, the entirety of gozora (including ssp. cinerea) spans Central America to the American Southwest. Phenotypically it varies from pale and virtually without blue in southern tropical areas to bright blue in semi-arid temperate regions. In northern New Mexico, cinerea is sympatric with other azures, specifically sidara and lumarco. In areas of sympatry, we have observed no evidence of interbreeding; each entity maintains its identity. We now understand the distribution of cinerea in New Mexico to be as indicated on the following map (Figure 6). Eventually, examples of cinerea are expected to be found from all northern New Mexico counties, perhaps except Union, but we do not yet have data to map those.

In Conclusion, considered as a whole, the evidence presented above leaves little doubt that cinerea is best treated a subspecies of gozora. That evidence includes persuasive transitional phenotypes at the continental scale. Evidence also includes shared multi-voltinism, such that gozora gozora is continuously brooded and gozora cinerea is multiple-brooded at the north limit of its range. Reproduction seems constrained only by growing season length. It seems cinerea and gozora interbreed freely where they overlap in northern Mexico and southwestern US, rendering them conspecific. In contrast, there is no evidence that cinerea reproduces with sidara or lumarco at the northern periphery of cinerea’s distribution. We conclude that cinerea is not reproductively linked to those entities.

More than a year ago Steve posted a story about distinguishing Dury’s Metalmark from Mexican Metalmark based on photos of live specimens. The bright green eyes of living Apodemia duryi faded after capture and curation, depriving collectors of an important diagnostic character which was readily available to watchers and photographers. In this present post, the tables are turned, showing that photos from nature have limitations and that sometimes only specimens will suffice to make an identification to species. Photos of azures on iNat and BAMONA are primarily ventral photos, perhaps 20 ventral views for every dorsal. And of the dorsal views, perhaps only half are females. Thus, photographers could spend many years trying to get enough dorsal female photos to confirm identifications for New Mexico’s azure species.

Acknowledgements. We thank Chuck Harp, Colorado State University, for his assistance accessing Gillette Museum specimens. We thank David Lightfoot and Simon Doneski for photographing specimens at the University of New Mexico. We thank Anisha Sapkota for photographing specimens at the McGuire Center. Jonathan Pelham offered helpful comments and insights.

Hi Steve and thanks for another information-filled post!! Anisha’s story of recognizing a mystery in the preserved specimens, then mentally recalling the characteristics while documenting a field encounter is a great example of focus over time and tenacity – congratulations on piecing the Tailed Cecropian puzzle together!!

Steve, Andy, Mike – your SW Azure synopsis and placement as a subspecies with the southern taxon is a joy to read and you make it difficult to assign an accolade. The thoroughness, reasoning, and inclusion of collaborative experts offers an amazing template for future research projects…Excellent work with a solid result – keep accepting challenges and having fun while making important contributions to science – many thanks!!

Bob and Rebecca wonderfully edited/and prepared this volume while preparing pertinent historical accounts into the Odonate material (as they did with the previous TBRN butterfly volume) providing a solid base of information and images of behaviors, to grow this infant collaborative project into the future! Butterfly observers and researchers regularly encounter damsels and dragons and their photo-documentation talents along with reporting the encounters will add substantially to this collaboration. An example – last spring, with guidance from Steve to examine western hackberry host trees/butterfly and caterpillar activity/bird predation, I also documented an Apache dancer which provided some connectivity between AZ and TX populations/collections of this rare damselfly species.

Jim, thanks much for your feedback on the butterfly stuff and the further enticements on odonates, which I agree are great photo targets and wonderful subjects for citizen science, especially in the arid Southwest. Keep your eyes open for Mexican damsels and dragons!