August 23, 2020

By Steven J. Cary

At this late stage of summer there are plenty of butterfly tales to tell. Some of them might even be true. I’ll let the protagonists tell a couple of the better stories, then you can decide.

First, outstanding birder, butterflyer, and professional guide Raymond VanBuskirk recently found a butterfly that was a lifer for him, as it would be for most of us: Ursine Giant-Skipper (Megathymus ursus). He tells the story like this:

“At 11:20 AM on August 7, 2020 just down slope from the Clanton Canyon Tank, in the Peloncillo Mountains of Southwest New Mexico, Jodhan Fine, Saunders Drukker, and I discovered a female Ursine Giant Skipper. She was flying rapidly in repetitive cycles around an area of about 100 sq. ft. in transitional habitat from yucca grasslands to mixed oak and Chihuahua Pine forest. . . . . Skies were light overcast. We first noted her large size (easily 3″ in length) and her rapid, audible flight. As she flipped passed us her wings made a soft cracking sound, reminiscent of some grasshopper species. Her wings were black, with large orange panels in the forewing, visible during flight. Even in flight her frosty blueish sheen and glowing white antennae were apparent. She rarely landed but when she did it was for less than 4 seconds in order to deposit a small whitish egg, with one reddish-brown splotch, on a yucca leaf. I obtained photos of her and her egg. . . What an amazing find! I’ve wanted to see this bear of a bug for many years.”

Johdan Fine managed to shoot a brief video of the ‘she-bear’ flying around in her oak/pine/grassland habitat. From that video I extracted a frame that shows her underside between flaps. Thank you, Mr. Fine, for this:

To underscore what Raymond and his colleagues accomplished, I add only that I have seen this butterfly once in 40 years. On July 20, 1986, Richard Holland and I made the hot, steep, sweaty ascent to the summit of Guadalupe Peak, in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas. We finished the uphill slog and walked guardedly toward the summit. We hoped to encounter a cool hilltopper, but we had no cover on the exposed approach. Suddenly, a skipper the size of a small bird vaulted off the ground and careened away; we were the startled ones. “That,” said Dick, “was Megathymus ursus.” It’s a vivid memory, but woefully lacking in details about the butterfly. Pictures are worth oceans of words, so KUDOS to Raymond and his crew for adding so much to our knowledge of this elusive beast!

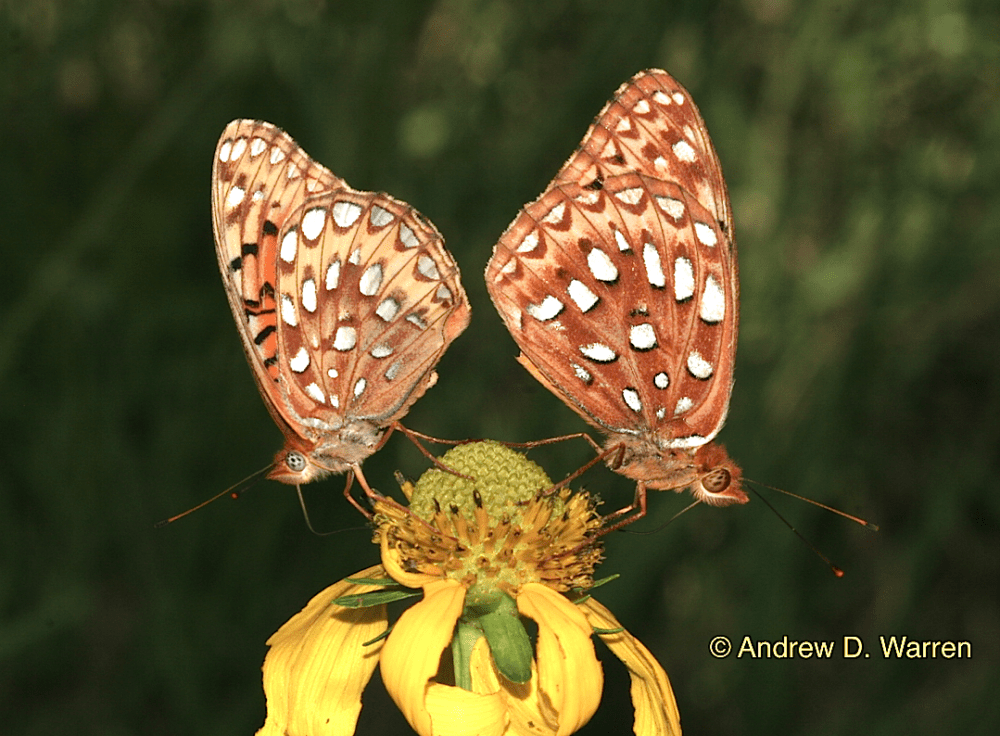

The second story revolves around Northwestern Fritillary (Speyeria hesperis) which has populations in all New Mexico’s major mountains. In Northern New Mexico, its gray-blue eyes quickly separate it from the amber-eyed Great Spangled (Speyeria cybele) and Aphrodite (Speyeria aphrodite) fritillaries. Below is a photo by Andy Warren, which he swears he did not pose by hand (believe him or not!), illustrating the difference between blue-eyed Northwestern (left) and amber-eyed Aphrodite in the field.

Interestingly, this eye color rule-of-thumb seems not to apply in Southern New Mexico. In the Sandia and Manzano mountains, for example, what we have for decades called ‘Dorothea’s’ Northwestern Fritillary (Speyeria hesperis dorothea) actually has tan or amber eyes, not gray-blue. So, one might wonder, are these even Northwesterns? Maybe they are Aphrodites or maybe a novel species. In his Swift Guide 2nd edition, Jeff Glassberg speculated that when this group gets more study “they may prove to be a separate species.”

Fortunately, more study is forthcoming. My Colorado friend and colleague, Mike Fisher, continues his quest to understand the fritillaries in the southern Rockies, including New Mexico, and he has undertaken the challenge to investigate ‘Dorothea’s’ Northwestern Fritillary. I had provided Mike with photographs featuring this butterfly’s puzzling tan eyes, taken back in July 2018 in Fourth of July Canyon in the Manzano Mountains. Now, Mike said the next step would be to collect several live females from which he could gather eggs and rear them into adults. Each female probably mates with two males on average, so collectively the hundreds of eggs from six females when reared to adulthood would produce a large and genetically-mixed sample of individuals. At least that’s my understanding. Eventually that should help Mike pin down what Speyeria . . . dorothea really is.

Luckily, I had been in recent contact with two eager field assistants: Ornithologist Hira Walker and her budding Lepidopterist daughter, Brooke (age 5). Hira and Brooke had been exploring Fourth of July Canyon this summer and they had been emailing me photos of fritillaries and other butterflies that Brooke had caught, seeking help with IDs. Furthermore, Hira had approached me for ideas for getting Brooke involved in more “hands-on” butterfly projects. So, long story short, they were ideal partners for me in carrying out the field part of Mike’s fritillary project.

Masked and socially distanced, the three of us converged on Fourth of July Canyon in late July. Brooke’s net-swinging skills were formidable and, with her help, we gathered up seven healthy females (see photo below). I slipped them into carefully prepared waxed paper envelopes and then into an ice chest to chill so they would not injure themselves trying to escape. Over the next 24 hours, I allowed them to siphon hummingbird juice from a soaked paper towel, then packaged them carefully into a small box, which I nestled into a bubblewrap-cushioned shipping box. I hand-carried the box to FedEx for priority overnight delivery to Mike’s colleague, Art, in Los Angeles. Mike said they all arrived safely and egg production had begun. Now Brooke, Hira and I have to wait to see what comes of this effort. It would be nice to know what that fritillary is, one way or the other. Inquiring minds want to know!

One day before Hira, Brooke and I converged upon Fourth of July Canyon to collect fritillaries, Hira told me via email that she had seen an intriguing “swarm” of butterflies under a willow shrub along the Rio Cebolla in the Jemez Mountains. So last but not least, here is her story:

Hi Everyone! First, I would like to thank Steve for inviting me and my daughter, Brooke, to share an exciting discovery that we made about the relationship between sap-sipping butterflies and a sap-eating woodpecker. Secondly, I would like to disclose that Brooke is obsessed with butterflies and this discovery would not have been made without her unflagging desire to find, capture, and study them.

In attempting to supply Brooke with enough butterflies to satiate her curiosity, we have spent much of this spring and summer exploring New Mexico’s mountains (8 mountain ranges at last count) and searching the usual places where one can find large numbers — kaleidoscopes — of butterflies. We scoured wet meadows of nectar-filled flowers and we examined damp soils along stream banks where puddling butterflies drink water and extract minerals. We didn’t know, however, that there was another place where we could have been looking for butterflies.

On July 26, as Brooke was busy capturing Great Spangled and Aphrodite fritillaries nectaring on cutleaf coneflowers and Parry’s thistle growing along the streambank, we noticed a swarm of butterflies under a Bebb Willow shrub. Intrigued, we investigated further, finding that the butterflies consisted of mostly Mourning Cloaks (upwards of 20 individuals at any one time) and also several species of commas. They were feeding on sap oozing from numerous holes in the willow stems, which were being drilled by a pair of Red-naped Sapsuckers and, from what we could tell, at least one of their young! As their name implies, sapsuckers are woodpeckers in the genus Sphyrapicus that drill through the outer bark of woody plants to create shallow sap wells that exude either phloem or xylem sap that the woodpeckers then feed on. There are four species of sapsuckers in the US, two of which regularly breed in New Mexico — the Red-naped, discussed here, and the Williamson’s.

Brooke and I had already noted that sap was an important food source for Mourning Cloaks, especially females coming out of hibernation on warm late-winter days, when a female surprised us by flying over our heads on February 18. Since then, we have learned that sap also can be a valuable food source — when other food sources are scarce, for instance — for other butterflies, such as anglewings, tortoiseshells, admirals, and wood nymphs. Incidentally, this is also true for hummingbirds, like Broad-billed and Rufous. But, when we thought of sap, we imagined it dripping from plant injuries induced by disease or insects. We had not considered sap oozing from sapsucker wells. Nor did we imagine that these wells would draw such a large gathering of butterflies.

During our observations that day and on two subsequent occasions, we found a cumulative total of six butterfly species feeding at the wells: Mourning Cloak, Weidemeyer’s Admiral, Question Mark, and Hoary, Green, and Satyr commas. The Weidemeyer’s Admiral was seen making a bee-line — or should I say, butterfly-line — straight to the wells from about 40 feet way. Finding all four of New Mexico’s ‘punctuation’ butterflies was quite a surprise as these species tend to segregate by elevation and habitat. Other animals that fed from the wells included the sapsuckers themselves, ever-present flies of various sizes and species, and a Southwestern Red Squirrel. It is no wonder that sapsuckers are considered keystone species! Their nest cavities are used by a number of other animals and, as we have now seen, so are their sap wells.

In addition to sap, sapsuckers eat insects and other food items (e.g., fruit), which leads one to wonder if the sapsuckers eat butterflies lured in by the sugary, sticky buffet. From what we have seen to date, it doesn’t appear so. We never saw a sapsucker eat a butterfly or any other insect attracted to the wells; the birds seemed disinterested in all other animals present except for us and the squirrel. Actually, on one occasion, a young sapsucker feeding at the wells was startled and scared off when a Mourning Cloak flapped over to its well (providing Brooke and I with a good laugh). For their part, the butterflies seemed somewhat unconcerned with the sapsuckers, but they often vacated the area while the sapsuckers were present.

Where did the butterflies go when they weren’t at the wells? It seems that they loafed about on nearby willows and thinleaf alders. Brooke and I followed the butterflies as they moved to and from the sap wells and realized that they did little else besides rest between feedings. In fact, it seemed that they also rested WHILE feeding. They were so tranquil and stupefied while sipping sap that Brooke could walk up to them and pluck them up with her thumb and forefinger. We can’t say for sure what is going on here to make these guys so sleepy, but we have found one possible explanation. After a little digging online, we learned that phloem sap is a water-based solution that is rich in sugars and contains other solutes such as hormones and minerals. Willow sap, in particular, also has salicin (an alcoholic β-glycoside), which, when consumed by humans at least, is broken down into glucose and salicyl alcohol (and eventually to salicylic acid, an active ingredient of aspirin). So, are these sapsucker sap wells serving up a sugary alcoholic drink to the butterflies? Ahh, it makes sense now why all the butterflies search out the sapsucker wells. Next time you go looking for butterflies, maybe you should do as the butterflies do, and head over to the sapsucker saloon …

Thank you Hira! Thank you Raymond! You have brightened our smoke-filled lives considerably.

As August enters its final week, I hope each of you is finding the butterflies you seek. I look forward to telling more tales next month. Do you have one to share?

Until then, please stay cool and stay safe!

Steve

Fascinating, we know so little about butterflies keep up the good job. Thank you for all the info.

Thank you Steve for the always interesting butterfly stories in tour blog. Brook sounds like she’s well on her way to becoming a lepidopterist!