© Steve Cary, July 31, 2024

My recent travels in north-central New Mexico revealed that landscapes are green, creeks have water, and conditions for butterflies are near normal. For me, dedicated searches in Sargent Wildlife Management Area and Sugarite Canyon State Park produced 30 butterfly species in each, and I consider that a good day. I hope you are having a good butterfly summer, too. In this month’s post we feature Mike Toliver’s timely article on common/English names. I sprinkle in some of my interesting July photos. First, here are some tidbits and announcements which I hope will grab your attention.

Kelly Ricks captured this fascinating courtship display among American Snouts. Check it out! https://drive.google.com/file/d/136JMSg0fRd2y1YzZBVHzvzBWMosJFntf/view?usp=drive_web

Disgusting Butterfly Feeding Habits. Last month, Tom’s tale about butterflies feeding at animal carcasses was a hit. We got some excellent comments, for example from Rozelle and Mike T. We also received a provocative suggestion which sounds doable, so here goes . . . . Looking ahead to Halloween, we invite readers to submit photos of butterflies feeding at dead animals or other spooky/disgusting/scary stuff. Please submit images to Steve at sjcary1@outlook.com. Please submit no more than 2 of your own images per person and include photo dates and locations. Our post which appears closest to Halloween (probably in early November) will include as many submitted photos as practical. I’m not sure how many we’ll get, so I don’t want to overpromise. I hope the image below encourages you to participate!

I am happy to refer you to two other bloggers who do butterflies: Lisa Tannenbaum (see her image above) posts photos of butterflies and anything else that catches her fancy (such as the total solar eclipse in April). You can sign up for her posts here: https://everydaymagic.substack.com/. Substack will likely try to get you to sign up for the emails if you click through but you can just tap the “Show me first” link to get past that.

Joe Schelling also blogs about his nature-related travels, which are heavily weighted toward New Mexico butterflies and birds. Joe invites you to visit the blog at https://joeschelling.wordpress.com/ where you should see a link to subscribe at the bottom right-hand corner. (It might be easier to see by clicking on the title of a single blog entry (e.g., https://joeschelling.wordpress.com/2024/07/31/july-2024/ ) rather than having to scroll through the last ten posts. On the matter of getting help with butterfly identifications, Joe is finding iNaturalist.org to be increasingly useful. He also says that eButterfly (https://www.e-butterfly.org/) recently released its mobile app, so you might check that out and see if it works for suggestions. Thanks, Joe!

National Moth Week was July 20-28, 2024! Moths are amazing creatures. Take photographs and share your moth sightings with BAMONA to document the moths where you live.

Conservation Win: Butterflies Proposed as Species of Greatest Conservation Need, by Simon Doneski. Every ten years each state wildlife agency is charged with rewriting their State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), a comprehensive conservation planning document that outlines priorities for conservation in the state for the next ten years. New Mexico Game and Fish is currently rewriting their SWAP and as part of this process New Mexico Game and Fish identifies Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in the state. These species are eligible for funding for conservation and research for the next ten years and are highlighted as conservation priorities. This year the butterfly community got some exciting news with the release of the SGCN list last week as New Mexico Game and Fish has included butterflies on the SGCN list for the first time in over twenty years. Butterflies were briefly on the states SGCN list when the SWAP was revised in 2005 however, they were dropped by Governor Martinez for political reasons soon after and since then butterflies have been without any state status or protections in New Mexico. This 2025 revision not only readds butterflies but adds many more species then were ever on the list before marking a huge step forward for butterfly conservation in the state. The public comment period is open now and we encourage you to check out the full list and leave a comment thanking the Department for recognizing that several of New Mexico’s butterflies are in need of conservation. The full list of proposed SGCN butterflies can be found below:

- Anasazi Dotted-Blue (Euphilotes ellisii anasazi)

- Apache Northern Crescent (Phyciodes cocyta apache)

- Capulin Mountain Alberta Arctic (Oeneis alberta capulinensis)

- Carlsbad Agave-Borer (Agathymus neumoegeni carlsbadensis)

- Chuska Mountains Anicia Checkerspot (Euphydryas anicia chuskae)

- Colorado Rita Dotted-Blue (Euphilotes rita coloradensis)

- Colorado Melissa Arctic (Oeneis melissa lucilla)

- Monarch (Danaus plexippus)

- Southwestern Great Basin Silverspot (Argynnis nokomis nitocris)

- Nokomis Great Basin Silverspot (Argynnis nokomis nokomis)

- Organ Mountains Poling’s Hairstreak (Satyrium polingi organensis)

- Rio Grande Gorge Yuma Skipper (Ochlodes yuma anasazi)

- Raton Mesa Boisduval’s Blue (Icaricia icarioides nigrafem)

- Raton Mesa Northwestern Fritillary (Argynnis hesperis ratonensis)

- Raton Mesa Silvery Blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus erico)

- Rocky Mountain Polixenes Arctic (Oeneis polixenes brucei)

- Sacramento Mountains Bramble Hairstreak (Callophrys affinis albipalpus)

- Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot (Euphydryas anicia cloudcrofti)

- Sacramento Mountains Coral Hairstreak (Satyrium titus carrizozo)

- Sacramento Mountains Silvery Blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus ruidoso)

- Sacramento Mountains White-lined Hairstreak (Callophrys sheridanii sacramento)

- Sacramento Mountains Boisduval’s Blue (Icaricia icarioides sacre)

- Sierra Blanca Margined White (Pieris marginalis siblanca)

- Socorro Chryxus Arctic (Oeneis chryxus socorro)

- Sunrise Skipper (Adopaeoides prittwitzi)

- Tundra Anicia Checkerspot (Euphydryas anicia brucei)

- West Coast Lady (Vanessa annabella)

- Western Hobomok Skipper (Lon hobomok wetona)

- Yuma Skipper (Ochlodes yuma yuma)

Here is a link to the public comment page: https://wildlife.dgf.nm.gov/commission/proposals-under-consideration/.

Simon Doneski

SJC: Thanks Simon! And here’s a recent butterfly conservation article that should get everyone’s attention: The Xerces blue butterfly went extinct. Meet its replacement. – The Washington Post

And Now our Featured Story:

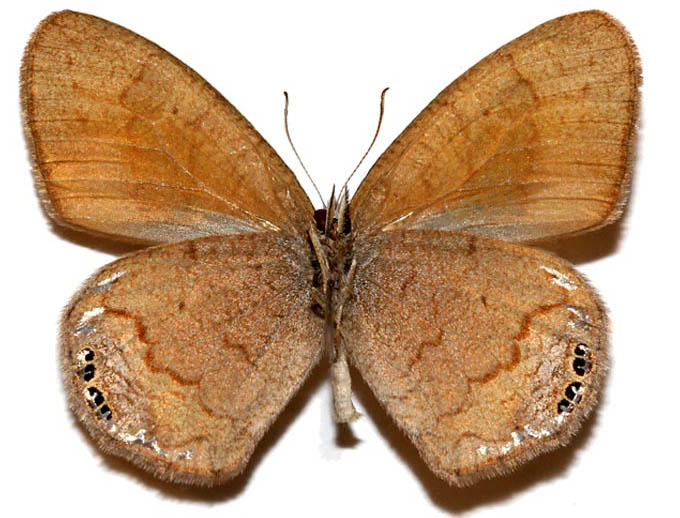

What’s In a Name? by Mike Toliver. Recently, in conversation with Anisha Sapkota about Boll’s Checkerspot (thanks, Anisha!) the issue of what common name to use reared its head. The issue came up again as I worked on more comparison plates for Butterflies of New Mexico. I was working on the genus Cyllopsis, the Gemmed-Satyrs, and was dealing with the various subspecies of the Canyonland Gemmed-satyr (Cyllopsis pertepida). However, some of those subspecies don’t have common names or the common names are not well-known. So, I was wondering what to call Cyllopsis pertepida maniola (Nabokov, 1943): “Arizona Canyonland Gemmed-Satyr”, “Arizona Gemmed-satyr” or “Arizona Brown” [Maniola is a Eurasian genus of satyrs with the common name “brown”, which Nabokov (yes, THAT Nabokov) studied and knew quite well]? Let’s face it – “Arizona Brown” is hardly an elegant name compared to “Arizona Canyonland Gemmed-satyr” or “Arizona Gemmed-satyr”! And yet, in the world of common names, “Arizona Brown” has priority (and sole use) as near as I can tell. Eons ago, there was quite the kerfuffle about common names, spawned by the publication of The Common Names of North American Butterflies, edited by Jackie Miller (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992). What follows is my attempt to address “what’s in a name”.

Common names of butterflies, which I suspect most of us use, are not the official names by which scientists recognize species. Scientists use the scientific name (ex. Cyllopsis pertepida maniola), which has the advantage of being universally recognized. Say that name to any lepidopterist anywhere in the world and she will know what you’re talking about, at least in theory. An official international body is dedicated to ensuring that scientific names of animals are properly used: the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (https://www.iczn.org/). That body ensures that strict rules are followed in the application of scientific names (for example, the principle of priority – all things being equal the oldest scientific name proposed for an animal is the one that must be used). No such body exists for the application of common names. As a result, common names vary for any number of reasons – regionally, personal preference, culturally. Thus, when I say “Mourning Cloak” in the United Kingdom, I may get puzzled looks from my companions, whereas if I say “Camberwell Beauty” I will get knowing nods.

One disadvantage of common names is that anyone can propose or create such a name, even for well-known species. I don’t like “Mourning Cloak” and I’m not from the UK – maybe I’d rather call Nymphalis antiopa the “Cream-bordered Tortoiseshell”! Offsetting that disadvantage (and some of the others) is the fact that most butterfly enthusiasts prefer common names to scientific ones. A sort of consensus in North America has settled on “Mourning Cloak” and I doubt that my “Cream-bordered Tortoiseshell” is going to catch on – thank goodness. Other disadvantages of common names include:

- They may not accurately describe a particular butterfly. For example (and this is my wife’s pet peeve), the Red-spotted Purple has orange spots and isn’t purple.

- The aforementioned “personal preference”: Jo Winter, former editor of the Lepidopterists’ News informed Bob Pyle (see below) in no uncertain terms that NO ONE was going to tell her that she couldn’t call Vanessa virginiensis “Hunter’s Butterfly” (I grew up calling it that, but now follow convention and call it the American Lady). [SJC: That name dates back to when its scientific name was Vanessa huntera.]

- Common names are frequently limited to particular regional geographic areas.

- Common names differ across the world; take “butterfly” for example. In English-speaking countries, our favorite creatures are most often called “butterfly”, but in other European countries, they may be called “papallona”, “sommerfugl” or “Schmetterling,.” to name only a few Imagine what they might be called in African countries, or Asian countries, etc.

- A single species may (and often does) have several common names.

- Because of individual, seasonal and sexual differences, the same species may have different common names in the same area.

- Common names often change over time.

- Rare species, species which for various reasons may not have caught the public’s attention, or recently described species, may not have a common name at all. For example, Ithomiola (Ithomiola) tesseroides Grishin (2023) has no common name, is a tropical species rarely encountered by butterfly enthusiasts, and was described last year.

- A single common name might be applied to several different species.

A “scientific” objection to the use of common names was published by Murphy and Ehrlich (1983, Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 22(2): 154-158.) based in part on these disadvantages. Murphy and Ehrlich contended that common names hindered two main purposes of science: communication and expression of relationships. They were answered by Pyle (1984, J. Res. Lepid. 23(1): 89-93) who noted that 1) “banning” common names would never be accepted by naturalists, and 2) common names often are more effective at communicating among the general public. He defended the committee that resulted in The Common Names of North American Butterflies.

Jackie’s book was intended as a guide for butterfly enthusiasts to address some of the disadvantages of common names. While that book didn’t dictate what name should be used, it did provide guidance on the most used version and provided alternative names (a sort of synonymy) that have also been used for each species. The controversy arose because a competing list was developed by Jeffery Glassberg (Official List of Common Names of North American Butterflies). Glassberg wrote a letter to the News of the Lepidopterists’ Society (volume 38: no. 4) outlining what he felt were flaws in Miller’s list and contending that the developmental history of Miller’s list did not merit its use. He was prompted to write that letter because Bob Pyle, in his review of Glassberg’s book Butterflies through Binoculars, (Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 50:161) called this list a “monumental redundancy”, given the previous publication of Miller’s book. Glassberg was answered by Pyle (News of the Lepidopterists’ Society: 38: no. 5), who noted that Glassberg’s understanding of the development of Miller’s list was mistaken. The rest of us were left wondering what is the “official” common name for butterflies? For example, what is the common name of Cyllopsis pertepida maniola? Aye – there’s the rub! Glassberg’s list doesn’t have one, while Miller’s does (oh, no – The Arizona Brown).

As it turns out, there is no such thing as an “official” list of common names for butterflies. The Entomological Society of America maintains a list of common names of insects and requires members to submit a formal proposal for a new common name before it can be used (https://www.entsoc.org/publications/common-names), but relatively few butterflies are included on that list. For example, only six Nymphalids (brush-foots, if you please) are in that list. The nearest thing we have is published by NABA (https://naba.org/butterfly-names-checklist/).

Now, what are we going to call Cyllopsis pertepida maniola? Maybe you all would like to vote: how many are in favor of “Arizona Brown” (for reasons of priority and the fact that it’s the only “official” common name)? How about “Arizona Gemmed-Satyr” (sounds better, tells you it’s in the Gemmed-satyr genus)? Maybe “Arizona Canyonland Gemmed-Satyr” (like the above, and has the advantage of telling you it’s a member of the Canyonland species – pertepida – but it is a mouthful)? Let us know your preferences! And don’t despair – chances are whoever you’re with will know what you’re talking about when you point and say “There’s an American Lady” (unless you’re with someone like Jo Brewer).

SJC comments: By all means, readers, please weigh in with your votes or opinions on this matter. Common (English for us) names, are a bit of a tangle because, as Mike pointed out, there are no rules, and attempts to arrive at rules provoked loud disagreements. It seems the best we can hope for is some level of mutual acceptance, if only to facilitate communication.

For example, a historical tracing of names applied to the species, Cyllopsis pertepida, shows that for about 20 years (~2000 – 2022) the common (English) name “Canyonland Satyr” was consistently used in publications. Recently, though, there have been efforts to make common (English) names more systematic, almost like scientific (Latin) names. For example, the term “Satyr” has been applied to many species in many genera within the Satyrinae, so its use as part of a common name doesn’t convey much information. Perhaps to remedy that, Butterflies of America now uses the term “Gemmed-Satyrs” for all species in the genus Cyllopsis. Thus “Canyonland Gemmed-Satyr” translates genus and species into English. Momentum is growing to develop common (English) names for subspecies, too. This is evident in Simon’s conservation article above, in which common (English) names are derived for SGCNs – how can we talk about them if they don’t have names? Applying that approach to Mike’s current question, I vote for ‘Maniola’ Canyonlands Gemmed-Satyr. We both look forward to your ideas and votes!

Best wishes to you all for a butterfly-filled August!

In regards to maniola, recent genomic analysis by the Grishin lab has determined maniola to be a different species from pertepida. Maniola is so far only known from the higher elevations of the Huachuca and Chiricahua Mountains in Cochise County, Arizona in the U.S. I do not know its status in Mexico? So perhaps this makes the application of an English name easier?? Kudos to Rich Bailowitz for seeing a difference in these two butterflies some years ago and being correct according to the Grishin lab. Both species occur in the Chiricahuas but only maniola is known from the Huachucas.

I’m betting they found avicula distinct as well.

Jim, thanks for that. Must be fun to have pyracmon, pertepida and maniola all frolicking around together. We have not seen maniola or pyracmon as yet in NM. We have suspected it is (they are) down in the Bootheel somewhere, but no luck so far.