© Steve Cary, February 8, 2023

My cold, dark, demotivated winter is disappearing in the rearview mirror, thank goodness! I have worked on this post since November 2022, but my effort has been erratic and unenthusiastic. January was very cold where I live, and all I did was change the blog title as I flipped calendar pages. But now the days are at least an hour longer and the sun actually produces heat! Spring is coming, sure enough.

So off we go into 2023. First, I share someone else’s cool Monarch story from Silver City. Then there are some announcements and then my own winter Monarch story. Happy reading!

First, a January news story just now arrived in my inbox (that’s how connected I am). A Monarch butterfly tagged in New Mexico this last autumn was re-spotted in January in California! That’s amazing! Read on:

There is an amazing new development that concerns Monarchs in New Mexico. You may have heard from other sources, but a Monarch tagged by young students this last autumn in Silver City was in Los Osos, California, in early January. You can read the full story by Jo Lutz here: https://www.scdailypress.com/2023/01/06/third-graders-make-important-contribution-monarch-migration/.

Thousands of Monarchs have been tagged in New Mexico during their autumn migration, but only three have ever been spotted again. The first two (tagged in Lea County and Bernalillo County) were re-sighted at the Mexican overwintering site used by Monarchs from eastern North America. This demonstrated that some of our Monarchs move along the so-called “eastern flyway.”

This latest discovery finally confirms what others have suspected: some New Mexico Monarchs head to California for the winter. Thanks to large-scale, multi-state tagging efforts led by Southwest Monarch Study, a Phoenix-based non-profit, it became clear several years ago that some Arizona Monarchs fly west to overwinter on the California coast while others fly south to overwinter at the central Mexican colonies. Now, thanks to excellent and dedicated work by Patrice Mutchnick and her Silver City network of schools, teachers and students, we know that New Mexico Monarchs split up the world in a similar way. This is a major development in Monarch biology/ecology in New Mexico. Excellent work by teachers and students!

ANNOUNCEMENTS:

1. I have a new email address: sjcary1 at outlook.com. Please adjust your contact info for me accordingly. I look forward to getting your emails.

2. If you post photos to BAMONA (butterfliesandmoths.org), you may know that an occasional submittal goes missing and does not get into a queue for review. If you have a submittal that seems to be languishing, go back and look it over . . . is the “Region” field empty? If so, click “edit” and type in the state and county of your sighting. Then the software will know which coordinator/reviewer to send it to. This little glitch is rare but can occur when a sighting is near a state or national border or in mountainous terrain.

3. The Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot Butterfly was formally declared “endangered” by the US Fish and Wildlife Service pursuant to the Endangered Species Act. Designation of critical habitat for the Sacramento Mountains checkerspot (SMCB)

will be proposed at a later date. Per USFWS biologist Betsy Bainbridge, the final listing rule for the Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot (Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2021-0069) was published in the Federal Register on Tuesday, January 31, 2023. All the listing documentation can be found here: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=FR. The final rule will be effective on March 2, 2023.

ESA listing is probably the last, best chance this butterfly has for survival and persistence into the future. It has declined from arguably the most abundant butterfly in its Cloudcroft-area habitat, to no more than a couple dozen individuals in each of the past two years. Narrow habitat specialists like SMCB are increasingly vulnerable as the footprint of Homo sapiens grows ever broader and heavier. We certainly hope it is not too late for this beauty.

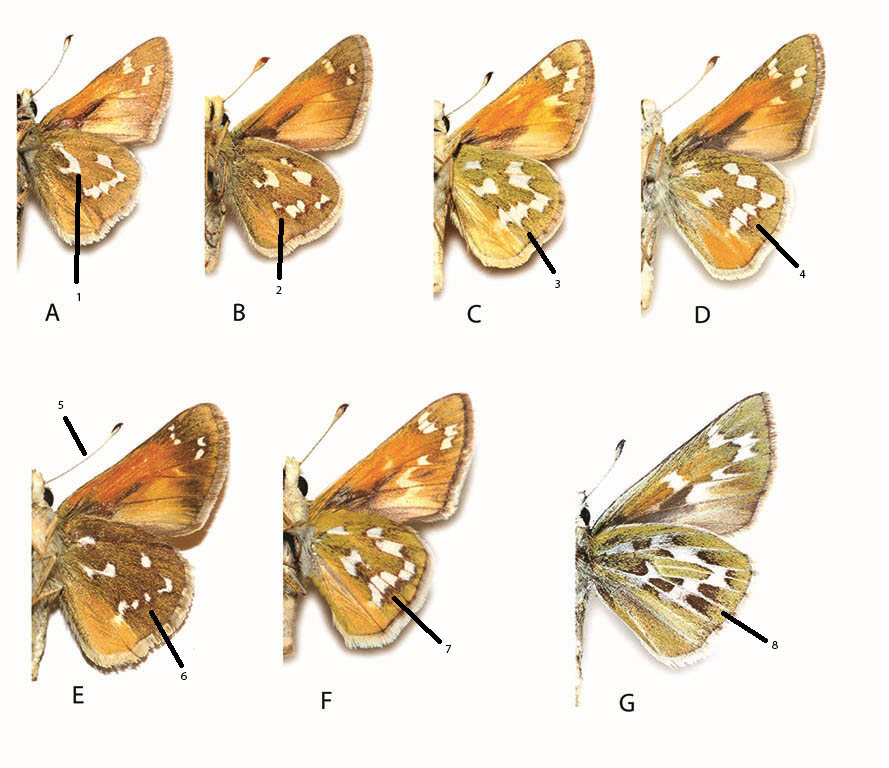

4. Distribution Maps. Mike Toliver and I (mostly Mike) have been plugging away at distribution maps and comparison plates for PEEC’s Butterflies of New Mexico. So far, the Swallowtails, Whites, Sulphurs, Coppers, Hairstreaks, Blues, and Metalmarks all have maps. Among the skippers, the Dicot Skippers and Spread-wing Skippers all have maps. We are well into the Folded-wing Skippers, then will come the Skipperlings. We saved the Brushfoots for last. We are a little more than half-done overall. Below is one of our recently completed maps and an example of the “comparison plates” Mike is preparing so readers can more easily compare and differentiate similar species. Please look into Butterflies of NM and tell us what you think.

5. SAVE THE DATES. I have a project in the planning stages involving Python Skipper and Margarita Skipper. If all goes well over the next several weeks, I expect to reach out in a future blog post seeking volunteer assistance in the field to find, photograph, and capture examples of these two look-alike skippers in New Mexico. My goal is to construct an accurate distribution map for each. Might you be available/willing to assist in May or early June? Much of New Mexico will be fair game for these two lovely skippers. Want to know more? Email me here: sjcary1 at outlook.com so I can add you to the team and answer any questions you may have.

And now here is your reward for reading this far . . .

California Coastal Monarch Groves. Marcy and I embarked on a trailer camping trip spanning most of November 2022. She needed some ocean/beach time, and I was happy to accompany her. Our itinerary included a “getting there“ segment, during which we camped one night at Homolovi State Park near Winslow, AZ. We spent our second night at Hole-in-the-Wall campground in California’s Mojave Desert National Preserve, which I hope to visit again when the weather is more auspicious. Our next two days and nights found us encamped within Carrizo Plain National Monument, followed by our triumphant arrival at Morro Bay. All these nights were on the chilly side, as one might expect in early November. Carrizo Plain National Monument (CPNM) seems not to be on the way to anywhere and thus not frequently visited. Tellingly, the BLM website touts it as “one of the best-kept secrets in California.” Its existence testifies to the persistence of conservation-minded local land-owners and to The Nature Conservancy. As a lifetime TNC member, I had read about it many times over the years, and so we decided to investigate it since we were in the neighborhood. At about 2000’ elevation, CPNM contains about 250,000 acres of land that is mostly grassland with some peripheral mountains, all of which drain to Soda Lake. Upon our arrival, our initial impressions were along the lines of “meh,” but as we explored over the next two days, we came to appreciate some of CPNM’s finer, if subtle, qualities. For example, the KCL campground was very basic, but it had a group of large eucalyptus trees where hawks roosted at night and which housed a pair of owls whose pre-dawn serenade boomed right over our heads. On our first morning, we drove/hiked to the San Andreas fault, which runs the length of the semi-enclosed valley. The Park offers a road, parking area, excellent interpretive signs, and a trail that takes you right to the fault trace at Wallace Creek, which has been bent over the years as the Pacific Plate scrapes episodically northwestward against the North American Plate. Visitors can stand with a foot on each side, straddling the fault. The fault scarp, perhaps 30 feet high in some places, can be traced for miles and can be seen from our camp at KCL. CPNM was created, in part, to preserve its largely intact and unusual grassland ecosystem that includes the expected pronghorn but also threatened or endangered mammals such as the giant kangaroo rat, San Joaquin kit fox, and antelope squirrel, not to mention an introduced population of diminutive tule elk. CPNM also is home to some terrific pictograph rock art. Marcy made the advance reservations necessary for us to access the pictograph site, and we were not disappointed; it was without a doubt one of the most outstanding we have ever seen (example below).

As a bonus, the trail to the culturally significant site was liberally decorated with at least two species of wild buckwheats (Eriogonum spp.), some even in bloom. Naturally, that made me wonder about possible late-flying dotted blues (Euphilotes spp.). The morning was sunny and warming, so I searched the plants intensively as we walked along. Sure enough, there were some blues, so I clicked off a few images. Later examination of photos (below) suggested two different species: a possible Dotted Blue (Euphilotes enoptes dammersi) and a possible Lupine Blue (Icaricia lupini). I submitted a photo of each to BAMONA, so now we wait to see what the California reviewer says. Whatever it is, I can’t complain about the result in early November while it was snowing at home in Santa Fe!

After two pleasant nights at Carrizo Plain, we headed for Morro Bay and the Pacific Coast . . . Marcy thoughtfully planned the core of our trip as a slow-paced 10-12 days along the Central CA coast. We arrived a day ahead of schedule and so found a spot at Morro Bay State Park, a haven for local golfers and sailors. We spent the day walking through town, out past the notorious three stacks to the famed Morro Rock, and back again. We sampled some locally farmed oysters and some local IPAs, enjoyed the sea otters, and admired the occasional Monarch butterfly that crossed our path in such a leisurely manner.

We checked in at Montaña de Oro State Park the next day, where we would spend six nights. We had camped there back in October 2019 and now, post-COVID, we seized the opportunity to return and enjoy what this fabulous place had to offer: walks along coastal bluffs, sea otters, harbor seals, falling asleep to the sound of the surf, hiking, tide pools at low tide. You know, the usual.

Over the length of our stay weather was pleasantly cool. Under a variable daily mix of sun and clouds, we walked the Bluff Trail, the Islay Creek Trail, and Pacific Gas & Electric’s Point Buchon trail, which is not far from the Diablo Canyon nuclear power station. On the one wonderful rainy day (if you thought New Mexico’s drought was bad . . . ), we spent time in nearby San Luis Obispo, (SLO, as the locals say): a winery, a craft brewery, grocery shopping, a poké bowl for lunch, ice for the cooler. Early one morning, we visited the aptly named Sweet Spring Audubon Sanctuary to enjoy the local shore and lagoon birds. California Quail frequented our campground.

Butterflies included what I presume constitutes the late autumn contingent: Painted Lady, West Coast Lady, Checkered White, Cabbage White, a Checkered-Skipper of some flavor, Lupine Blue, and a Buckeye. Given our location at the far western edge of the continent, I understand there is zero chance of having Common Buckeye of the eastern US here, so this must have been a Gray Buckeye. According to my sources, this assortment of species is very similar to what continued to fly in far southern New Mexico back in November when conditions permitted.

Monarchs were there, too, but not in great numbers. On most sunny days, we would see one here, one there, going to nectar, or wandering aimlessly. Toward late afternoon it was normal to see a couple in and around the treetops (Eucalyptus, a local pine, or a local cypress). Still, we never saw any roosting individuals or clusters. Nice to see them, always.

There was a designated Monarch Grove at the west end of the community of Los Osos, on the ocean side of the road, maybe two miles from Montaña de Oro State Park. We knew we were close to the Grove when we saw the official (yet somehow puzzling) sign adjacent to a regular neighborhood. The Preserve consisted of a large stand of tall Eucalyptus trees with a few trails and a bench.

At Los Osos Grove, we saw 2-300 Monarchs. Most were basking on east-facing Eucalyptus tree branches about 25 feet off the ground.

The next stop on our journey was a 2-day stay just an hour south at Pismo State Beach. It is a well-known destination because A) they encourage visitors to drive on the sandy beach (it is California, after all) and B) it has a large Eucalyptus stand that for many years has been a popular roost site for wintering monarchs. Managed by California State Parks, the park/grove is well equipped and well-staffed to interpret the west coast population of Monarch Butterfly for the many people who come to see them.

We arrived at this Monarch Grove just as it was opening one morning. We entered slowly with several other people, sipping coffee and looking around for Monarchs. The first to catch our eyes were a couple of dozen Monarchs lying or standing on the cool, damp, shaded ground – easy to spot but a dangerous place to be. Several (Monarchs) looked dead, and concern was evident on many faces. A fellow (who raised Monarchs at his home) and I were confident we could move them without hurting them. With the blessing of arriving docents, we gently plucked them from the cold ground and placed them on sunny branches one by one. To the amazement of disbelieving visitors, most slowly came to life.

No one came to the Grove to see only a dozen Monarchs. Air temperatures were not yet above 55˚, so it was still too chilly for them to fly. Where were the Monarchs? Where were the legendary clusters weighing down tree branches? We all craned our necks looking for them. As it turns out, a tree full of Monarchs resting with wings closed looks much like a tree with branches stacked with pale, dead leaves. Eventually, the morning sun worked its magic, provoking some Monarchs to open their wings and reveal their presence. They had been in plain view all along.

Over two days, we visited three times and saw thousands of Monarchs. Population estimates while we were there ranged from 16,000 to 24,000. A week earlier, they estimated they had 300,000, but the aforementioned rainy day apparently dispersed them. As I write this, an article in today’s Santa Fe New Mexican touted recent estimates of the West Coast Monarch population at more than 600,000 this recent winter. That made two consecutive years of increases from a dismal low in 2020 when Pismo State Beach had only 80 overwintering Monarchs.

We also saw hundreds of intrigued people who ranged from child to golden-ager and from novice to expert. Visitors were very curious and respectful and asked good questions. Volunteers were outstanding, providing spotting scopes, information, inspiration, and knowledge. Naturally, there was also the obligatory swag wagon, where visitors could spend money to support the non-profit that served Preserve.

Overall, it was a terrific experience, largely due to efforts of docents such as Barbara Hagerty, below. Now in her 20th year as a Monarch docent, she explained a little about cluster dynamics in a roost. In particular, there is rather a lot of moving around from day to day, roost to roost. Another visitor asked if the (non-native) Eucalyptus trees were necessary for the Monarchs? Barbara commented that Monarchs were doing this dance long before Eucalyptus trees were imported from Australia 150 years ago. Eucalyptus does grow tall in dense stands, and that appeals to Monarchs. Still, the native coastal cypress, cedar, cottonwood, and sycamore, despite being more bulky than tall, must have sufficed before human intervention.

As we moseyed along to make room for other arriving visitors, I heard her explain some basics of Monarch behavior. As you all may know, Monarchs in breeding season around milkweeds behave either with unmistakable territoriality (males) or with retiring discretion and aloofness (females). During winter, however, as Barbara explained, individual Monarchs did not even know if they were boys or girls. Hence their languid, worry-free nonchalance. These are the pressing issues for Monarchs on most winter days: shall I wake up? Is that another Monarch? Meh. Maybe later I can bask in the sun, maybe find some nectar, maybe not. Then definitely have a nap.

As far as we know, there is nothing like these aggregations in New Mexico, so you have to go somewhere else to see them. I highly recommend visiting one of the many known, staffed and interpreted Monarch overwintering preserves up and down the California coast, of which Pismo State Beach is but one.

HAPPY BUTTERFLYING!!

Those California Quail do look almost identical to Gambel’s don’t they? (It’s a range thing: no Gambels along the coast.) I’m glad you were able to get away for what appears to have been a great winter trip! And thank you for all the instructive photos and descriptive information, almost all of which is new to me.

Steve! Welcome back to blogs. As always you have come up with amazing information on Blues my favorite. The monarchs in California increase is awesome! Eucalyptus trees seem like the reason. I have seen these majestic trees in South India Ootacamund ( Ooty ) same altitude as our Los Alamos.

I hope Blues and Monarchs visit our yard.

Selvi, it’s great to hear from you. I hope you get lots of blues and monarchs. too. Eucalyptus trees are magnificent.