© Steven J. Cary, August 31, 2002

We will get to the Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot update in short order. First, here is a story from our Nepali students at Eastern New Mexico University, which did not quite arrive in time for my last post.

A Blissful Weekend, by Anisha Sapkota. All the way from Nepal to the opposite side of our world, the U.S., Sajan and I were thoroughly excited and overwhelmed for what present was unfolding in front of us. We arrived at Eastern New Mexico University, Portales on January 1, 2022. What a way to start a year, isn’t it? I must say, the early days were busy with the new challenges for adjustments in the new environment and the university schedules.

After staying in Portales for a few months, Sajan and I already knew Portales and Nepal are two different poles, in culture, in faunal diversity, in climate, in geography and so on. Above all, not seeing a lot of insect diversity was a bummer for us, because we came here to study insects! For butterfly lovers like us, Portales’ butterfly diversity was a drop in a bucket. We were starting to think New Mexico has limited butterflies to offer us. The cold and harsh winter in Portales would just show us a few grasshoppers jumping here and there. Spring came, however, with blissful warmth and blooming flowers. We would go out daily and roam around each lawn of our university in search of butterflies, but the time invested wasn’t worth it. Having no vehicle in the US is like having no legs, we couldn’t go out far in search of new butterfly habitat. Also, the long drought had hit the state hard, except for the fully irrigated lawns, there was no green at all! It was very demotivating for us.

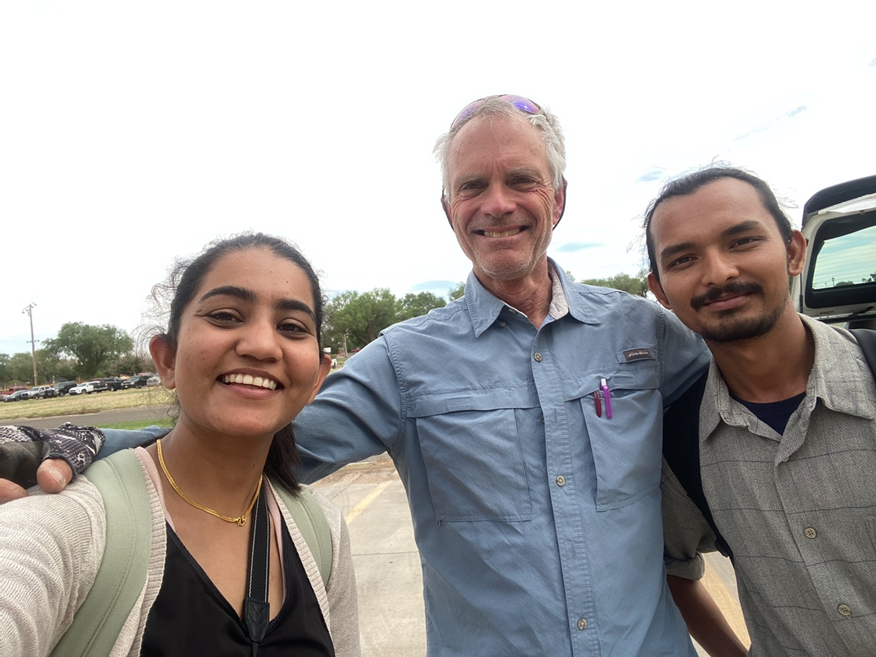

By the spring, we were already the fans of the https://peecnature.org/butterflies-of-new-mexico/, a webpage amazingly handled by Steven J. Cary and Michael E. Toliver, hosted by Pajarito Environmental Education Center (PEEC). To our great pleasure, Steve offered us a visit and introduced us to greener parts of New Mexico. We were on cloud nine. Together, we went away from Portales for butterflying in the first weekend of June.

On the first day (June 4, 2022), we set our journey for Ruidoso early in the morning. On our way, we stopped at several butterfly habitats. One of such spots, a marshy land indeed, gave us our first lifer for the day, Western Pygmy Blue (Brephidium exilis), the smallest butterfly of North America. Sajan was searching for it on campus for quite a time as Chenopodium, WPB host plant, is found in abundance at the university. It was a pleasure seeing our first WPB there. We both got a good shot of WPB and we continued our journey to Lincoln County.

Just after we entered Lincoln County Sajan saw another lifer, Margarita Skipper (Atrytonopsis margarita), from inside the car! What a welcome gift it was! We also got Hackberry Emperor (Asterocampa celtis) at the same spot, but it was dead and the ants were feasting on it.

The first spot in Ruidoso had an amazing butterfly habitat. It had a river, many wild flowers, trees, moist soil with leaf litter and shade. The earthy smell of the place kind of reminded me of Nepal. There were several Painted Crescents, a few Grey Hairstreaks, and another fresh Margarita Skipper nectaring from wild Petunia. The fifth lifer was Ceraunus Blue (Hemiargus ceraunus) which I initially ignored, mis-identifying it as Reakirt’s Blue. Sajan also got his first good shot of Mourning cloak (Nymphalis antilopa). There were several Painted Crescents and a few Grey Hairstreaks as well. A strange sighting on that spot was that there were several caterpillars of Mourning Cloak, probably in their last instar, dead on the ground. Steve suggested that some disease might have caused the death.

We were having lunch when Steve called us informing that he saw a Hairstreak. We wolfed the food down, grabbed our cameras and ran towards him. The rest is history. We got a Juniper Hairstreak (Callophrys gryneus) ! I was swooning to witness its beauty. It was a dream-like experience to photograph it and on top of that, there were two individuals! I took no time to declare the weekend as our best weekend here in the States.

We stayed there for nearly three hours. Clearly, I didn’t want to leave that place but we all know that a good time doesn’t last long. I reminded myself of a line from Robert Frost’s poem:

‘And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.’

and left that place with heavy heart.

Lincoln National Forest was closed because of fire hazards so we decided to return back to Portales before long. Ruidoso was greener and way livelier than Portales. For the first time in the States, we saw people walking here and there on the streets for real. Ruidoso was just like Sajan’s hometown, Pokhara.

The next day we went to Sumner Lake State Park to find hundreds of Marine Blues and Reakirt’s Blues mud puddling. I suppose I saw a Viceroy and Sajan claims to have seen some Tailed Sulphur, we both weren’t able to photograph them. Then we stopped at Melrose Trap just to get some beetles. Towards the end of the day, Steve drove us to Ned Houk Memorial Park, Clovis, where we found hundreds of Marine Blues once again along with Reakirt’s Blues puddling near a lake. We got no lifer on the second day of our trip but talking to Steve and traveling with him was such a great pleasure. We got to know a lot about butterflies of New Mexico. We are very thankful to Steve for offering us a ride and spending a fun time with us.

We now believe New Mexico isn’t just a dry and desert state. It has a lot of habitats and butterflies to offer us. Throughout the travel, we were very amazed by the knowledge and experience Steve has acquired throughout his years of work on butterflies of New Mexico, and we hope to achieve the same one day.

Thank you Anisha! I hope it’s OK for me to add my own photo below. That Juniper Hairstreak did not have a chance with you and Sajan surrounding it. Dear Readers, are you getting the correct impression? Nowhere in New Mexico are there more avid and energetic butterflyers than Anisha and Sajan. If you have an opportunity to chase butterflies with them, you will not be disappointed.

Checking in on Checkerspots, by Betsy Bainbridge. In May, we requested the help of volunteers to conduct expanded surveys for the Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot Butterfly (SMCB) during July. As you might recall, this species is proposed to be federally listed as endangered. The goal of these surveys was twofold: to increase detection of the SMCB and to begin a captive rearing effort at the Albuquerque BioPark, BUGarium. Many of you responded and took time out of your busy schedules to help. For this, we at the Fish and Wildlife Service are so grateful!

The SMCB has historically been a common sight in Cloudcroft’s meadows between June and July. Initially, it seemed that the SMCB surveys were off to a good start, with several individuals spotted on June 26th. However, rain and cold weather moved into the area and persisted over the next few weeks. Subsequent SMCB sightings were sporadic, and our team struggled to find windows of warm, sunny weather where we might see the butterflies.

Through teamwork and perseverance, we eventually collected four butterflies to start the captive rearing effort at the Albuquerque BioPark – two males and two females. Luckily, both the females mated upon arrival at the BioPark and quickly began laying eggs. At last count, each female laid more than 350 eggs – roughly 700 eggs overall! There is still a lot of work ahead to successfully rear the checkerspot butterflies in captivity. However, because of the work by the BioPark, BioPark Society, Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service, and volunteers, we’re now headed down the road towards conservation.

Volunteers were an essential part of this effort. We would not have been successful at starting a captive population without the help of interested people! We’re hugely grateful to the passionate folks who showed up to help the SMCB! Because of them, the species has a brighter future.

— Elizabeth “Betsy” Bainbridge, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Mexico Ecological Services Field Office, Aquatic and Terrestrial Conservation Branch, 2105 Osuna Rd NE, Albuquerque NM 87113

One example of Betsy’s “passionate folks” . . . by Hira Walker. Tuesday, July 12: We started surveying Bailey Canyon south of NF-568 at 9:30 am. We finished at 1:15 pm. There was a slight breeze, but it was sunny and the sky was cloudless until the conclusion of the survey, when thunderheads appeared to the southwest. We immediately began seeing many butterflies and knew that the day held promise. The ground was wet and many butterflies were sunning themselves on the grass or logs. As it warmed up, butterflies started nectaring at dandelions and a few of the sneezeweed (sneezeweed was rarely encountered in sizable patches, but it was scattered along the route; however, it was not heavily used by butterflies). A few flowering penstemon were found. Other flowers included yarrow.

When we reached the earthen dam, we spread out across the wide meadow to survey. Just before 11:00 am, my daughter Brooke spotted a Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot puddling near a pond of water formed at the base of the earthen dam. The rest of us were 50 meters or more away. The Checkerspot flew up when Brooke approached so she tracked it for about 10 meters as it flew rapidly. When it landed to nectar at a dandelion, Brooke carefully approached it, then gently captured it with a light aerial net by creating a cone shape with the net and carefully placing the net-cone over the butterfly. I went over to verify the species and determine the sex (= male) of the butterfly. Without touching the butterfly, I carefully transferred it from the net into a well-ventilated carrier container (to which, later on, two dandelion flowers and a penstemon flower spike was added).

We continued to survey the area, including meadows SW of the earthen dam, for other Checkerspots for another 1.5 hrs. During this time, the butterfly was kept in the container in complete shade (it remained motionless with closed wings most of the time). After completion of the surveys, as we hiked out a side drainage to our vehicle under threat of a thunderstorm, we saw a probable Checkerspot fly by. It was flying too fast to capture, but I had a good ventral view of it and concluded that it was very likely the Checkerspot. The captured butterfly was carried to the transport vehicle, where it was gently transferred from the carrier container to the transport container without touching it. This transport container was placed in a picnic cooler on top of two icepacks that were covered with a towel. Approximately 5.5 hours later, the butterfly was delivered to Jason Schaller (Curator, BUGarium, Albuquerque BioPark) for inclusion in the captive rearing program. Success!!

During our survey, we encountered at least two Definite Patch butterflies (see Steve’s photo below), which are similar in appearance to the Sacramento Mountains Checkerspot. We were very surprised to see this species as we were under the impression that it occurred at lower elevations. My husband Glenn caught the first Patch just SW of the earthen dam before Brooke captured the Checkerspot. We all gathered together to study it and discuss how the Patch’s markings differed from those of the Checkerspot (e.g., the Checkerspot has orange eyes and antenna, checkers all the way up to the tips of the forewings, and orange, instead of white, edging on the forewings).

The second confirmed Patch was seen doing a swirling upwards flight with a Checkerspot and was captured by Brooke. I relocated the Checkerspot when it landed and nectared on a yarrow flower. It flew, as Brooke approached with the net, and could not be relocated. We observed another swirling flight of two checkerspot-type butterflies nearby a little later on, but we could not confirm if the individuals were both Checkerspots, both Definite Patches, or a combination of both.

Steve adds: The efforts of Hira, Glenn and Brooke were among the most successful of all the monitoring participants. While many other volunteer monitors, like me, saw no Checkerspots whatsoever, captures by Brooke, Glenn and Hira were pivotal in initiating the captive breeding program. More on that below . . .

The Checkerspot Captive Breeding Program is being housed at the Albuquerque BioPark where it is being managed by Jason Schaller, Curator for Entomology. They began with two males and two females, but one male was rejected by the two females. Altogether, the two females and one remaining male produced nine egg clusters totaling more than 800 eggs. That was a great start.

By early August, after routine losses due to infertility, etc., they still had about 150 larvae, all 4th instars. Of these, 57 are from cluster A1 (female FA22, 100 eggs counted) and 92 from cluster B1 (female BA22, 150 eggs counted). The details of parentage of the larvae are important because the program wants to maintain as much genetic diversity as possible.

Of course, all these cats need fresh penstemon tissue to eat, which means Jason is raising penstemons and Checkerspots. He elaborated as follows: Cluster A1 had 20 larvae remaining on the original plant (which had been 75% consumed), and the other 37 were divided among 6 plants (groups ranging from 5-10 caterpillars). Cluster B1 completely finished their wild NM penstemon and were redistributed among 12 wild NM penstemons (groups ranging from 5-15 caterpillars each).

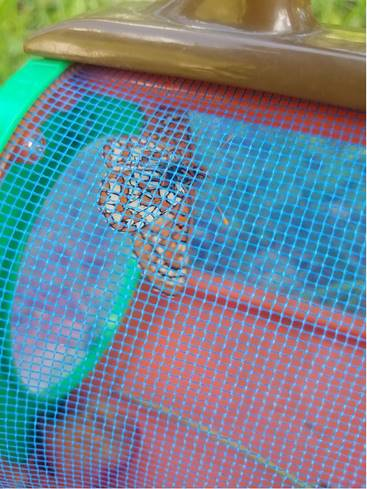

From the second image above you can see that SMCB larvae make themselves a tent-like shelter, which offers some protection from predators and parasitoids. This is typical for Variable Checkerspots. Thankfully, toward mid-August, the 4th instars ceased feeding and began to enter diapause, becoming quiescent in their silken tent. This is their routine in nature, too, as late summer brings less favorable weather to mountain meadows and food quality deteriorates as a result. Jason believes all the larvae are healthy going into diapause. Their next challenge is to get through winter – – – in the fridge, which will simulate winter. We can tune in again in April when they will be taken out of winter, break diapause, and start looking again for fresh penstemon tissues. We’re all keeping our fingers crossed!

The above information originated with the extremely busy, yet helpful, Jason Schaller, the BioPark‘s Curator of Entomology. The City of Albuquerque recently ran this article.

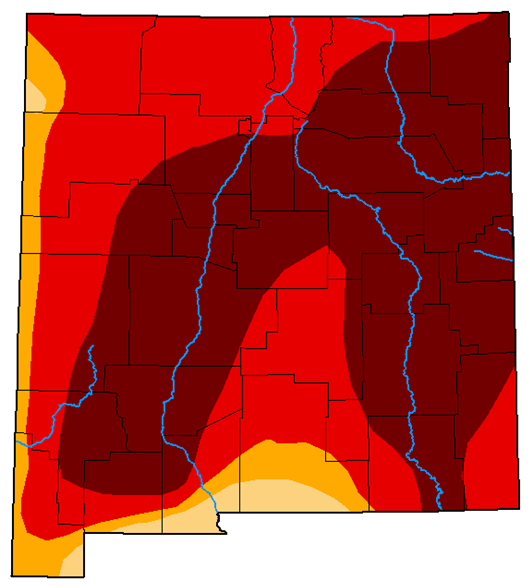

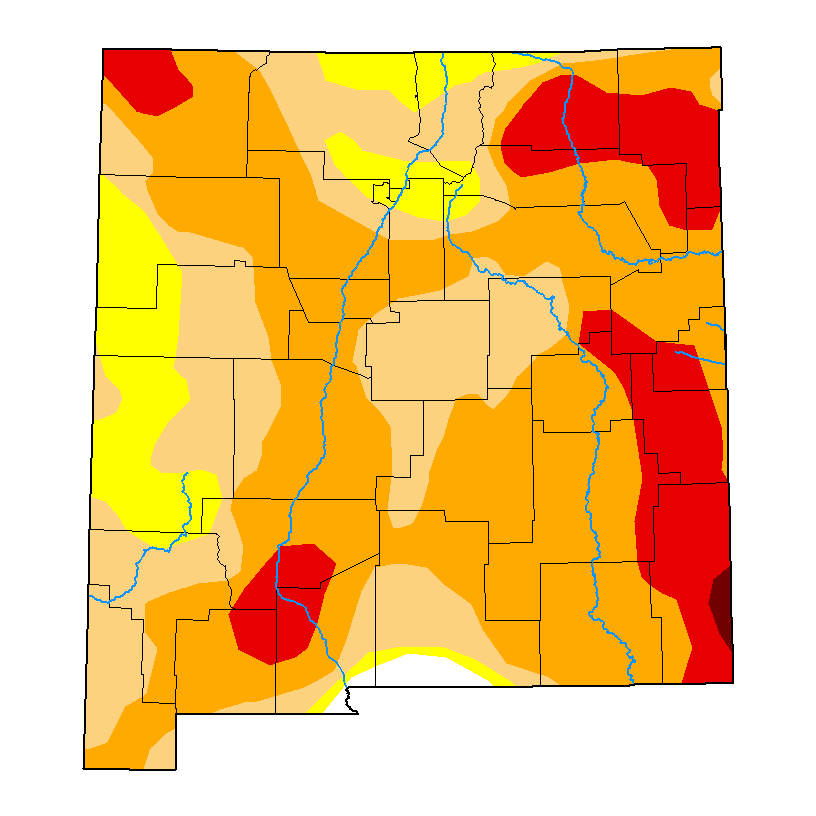

If you are watching the U.S. Drought Monitor, as I do constantly, you may have noticed some changes in New Mexico. The situation was very grim in early June, as you probably recall from personal experience. Since then, many parts of New Mexico have been blessed by multiple generous doses of precipitation. North-central NM, for example, my own home territory, has improved from extreme (red) and exceptional (brown) drought to abnormally dry (yellow) and moderate drought (tan). My house is a good example; we have recorded about 9 inches of rain since June 14. Weeds are going bonkers.

Generous rains have brought life back to local ecosystems. Green is everywhere, flowers, too, and oh, the weeds! How are herbivorous insects, like butterflies, faring? Well, results from my one-day outings into Santa Fe, Taos and Rio Arriba counties have been “interesting.” I have found butterflies to be rather sparse in terms of numbers and species richness. A few species are out in decent numbers, but most are represented by one individual here or there. Instead of seeing 20 or 25 species on a sunny monsoon August morning, I have been seeing 5 to 10 species. Surprisingly, the butterfly species we consider almost ubiquitous have been rather hard to find. Checkered Whites, Dainty Sulphurs, Orange Sulphurs, Reakirt’s Blues, Common/White Checkered-skippers, and Variegated Fritillaries have been very few and very far between. The fascinating subtropical strays, which often accompany a good monsoon, also have been largely absent. This may be attributable to the even worse drought that plagues northern Mexico. There are no butterfly resources down there either.

On the plus side, some very interesting species have made good appearances. The Rio Grande del Norte National Monument includes the famous Rio Grande Gorge, but also the adjacent Guadalupe Mountains, which no one ever goes to because access trails are not obvious, and then there’s the Gorge, home of ‘Anasazi’ Yuma Skipper. I went to the Guadalupe Mountains with the specific objective of documenting Indra Swallowtail (Papilio indra) as a breeding resident. I went hoping to see/photograph one or more hilltopping males. I did see one, I think, but my timing was off by a couple months and I got no confirmatory photos. But sometimes when I go out with a particular goal, I finds other cool things, too, or instead of.

In this case I was excited to see Spalding’s Blue in the midst of a normal looking summer brood, hosted by its sole larval host, Redroot Buckwheat (Eriogonum racemosum). There were males and females, and I got some photos. This would be only the second record of Euphilotes spaldingi from Taos County. Of course, it has been there all the time, but no one looked in the right spot.

I did photograph Indra, too, but it was more by accident, nectaring at Horsetail Milkweed along the Gorge rim as I was driving out. My working hypothesis is that Indra breeds in the volcanic summits/mountains on the Taos Plateau, possibly using as its larval host a rare plant called Spellenberg’s Springparsley (Cymopterus spellenbergii). It uses Cymopterus spp. elsewhere in its range, and this is the Cymopterus that grows here. I think I saw a worn male hilltopping on South Guadalupe Peak, but I was unable to confirm that, so that becomes a project for May/June next year. I did see and photograph (poorly) a female Indra over by the Gorge rim, just as Bob Friedrichs did almost exactly one year ago. My hypothesis includes the notion that gravid females disperse between high spots to place their eggs, thus ensuring that there are Indra eggs in multiple sites across the Taos Plateau. The Gorge Rim milkweeds give them a place to refuel en route.

The following week I drove to San Antonio Mountain on the west edge of the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument and the west edge of the Taos Plateau. This area missed out on the late June rains that fell in much of northern New Mexico. It was green enough by August 10, but it seemed a less developed, shallower, thinner, more tenuous green. Rather than making the ascent to the 10,000 foot summit, I was more interested in the wild buckwheat growing around the foothills, where I hoped for more of the Rita Blues (Euphilotes rita coloradensis) I had seen back in 1986.

U.S. 285 goes north from Española through Ojo Caliente, curves eastward up onto the Taos Plateau, and then steers north through Tres Piedras en route to Colorado. I exited and turned west onto Forest Road 87, which arcs around the southern base of San Antonio Mountain and heads west. I saw much of the wild buckwheat hostplant that I hoped to see, but the morning was cool, misty, and slow to warm, which may explain why I saw no Rita Blues. After an hour, I turned my attention to Los Cerritos de la Cruz, two little volcanic nipples southwest of the volcanic hulk that is San Antonio Mountain. The sun slowly gained the upper hand as I began walking. Insects in general, butterflies in particular, were few and far between. I finally spotted an Arachne Checkerspot (below). Mead’s Wood-nymph was the next to fly (below). These are interesting butterflies and I thought more things would appear. However, by the time I had summited the lesser Cerrito and returned to my truck 90 minutes later, all I added to my list for the day were a few worn Boisduval’s Blues and a few Small Wood-nymphs.

Results like that on a pleasant mid-summer morning invariably cause a person to scratch his head and move to another spot. I had not given up on Rita Blue, so I drove slowly along FR 87 as it angled west. I stopped to ogle roadside wild buckwheat patches, but no Rita Blues came to my eye. As I rounded a curve and descended toward a small stream crossing, I saw to my right a meadow that was wall-to-wall flowers, and many of those were Redroot Buckwheat, famous host for Spalding’s Blue and Blue Copper. The field was full of these knee-high spikes of pinkish-white flowers so there had to be something interesting there. I pulled over and waded into that meadow.

Well, yet again there were not many butterflies. I did see some activity around the buckwheat. Close approaches revealed Blue Coppers, a favorite of anyone who has ever seen one. I saw several of the gray/tan females, so clearly it was late in their flight period. Eventually I found and snapped a male that was showing some wear and fading.

Blue Copper larvae are hosted by Redroot Buckwheat, but so are Spalding’s Blue larvae. Were there any Spalding’s Blues about? I spent what seemed an inordinate amount of time looking for a species I had seen a week ago. It had to be there amongst all those healthy E. racemosum. Finally I kicked up a blue that showed Spalding’s submarginal orange on ventral hindwing and ventral forewing. Spectacular every time I see it! But wait, something was amiss. Uppersides were not Spalding’s. By golly, these were Melissa Blues. I had been so beguiled by the buckwheat that I jumped to conclusions. It was odd, though, to see Melissa Blues (males and females) cavorting on the buckwheat as if they were Spalding’s Blues. The buckwheat does offer a lot of nectar in a flower that is quite accessible to Melissa Blues, and in the photo below you can kind of see the proboscis dipped in a flower. Still quite odd; never saw Melissa replacing Spalding’s before.

The hour I spent in that 5-acre meadow should have produced a dozen species and dozens of butterflies on a normal summer day. That day, I saw several Blue Coppers, several Melissa Blues, one Orange Sulphur and one Mourning Cloak. Puzzling. It was some small consolation to find a Western Sheepmoth in the grass. I think it was dead, but it sure caught my eye. A lovely thing indeed.

The drought we are in is a deep one. All we can do is pay attention to how each butterfly species reacts and responds to precipitation, or the lack thereof. There will be no more “normal” years.

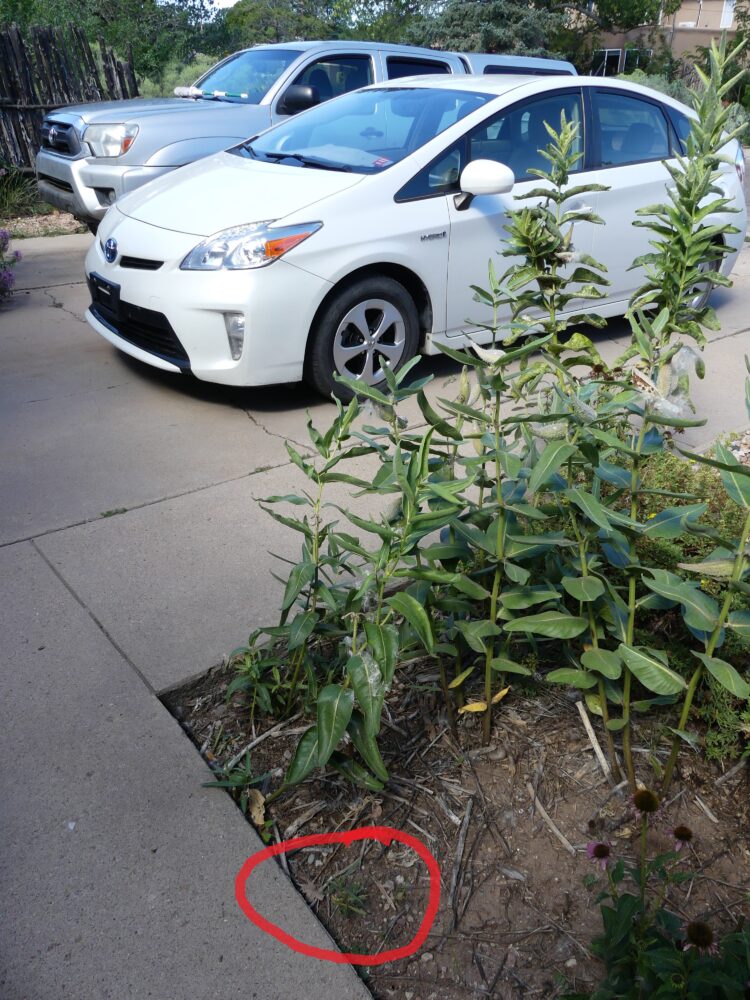

Monarchs Butterflies continue to reproduce around New Mexico. When I was out chasing Dotted Blues in San Juan County recently, Marcy was at home keeping her eyes open. She spotted a female Monarch on one of our milkweed plants.

You can see from the image above that we have several 3-foot tall, mature, aging, Showy Milkweed plants in that patch. They bloomed in June, were full of pollinators, and now have crunchy leaves and about 25 plump seed pods ready to burst. When I returned home the next day, Marcy said a Monarch had been slowly noodling around the milkweeds and had a photo to prove it (above). She saw it spend a little extra time in one particular spot (circled in red in above photo).

What is in that spot that would make a female Monarch ignore the mature milkweed plants and spend a little extra time? A relatively young showy milkweed seedling. It’s 4 inches tall – barely noticeable. On the underside of a leaf she placed an egg (see the images below).

Clearly, Monarchs continued to breed in Santa Fe in through August. The eggs they placed will (we hope) produce the migratory generation.

It has been more of the same down in Las Cruces: from Jim Von Loh . . .

Hi everyone – well Tuesday (August 24th) was an odd “faux desert” scene with damp soil, dew, humidity, and a cool S-to-N light wind blowing up the Rio. But, as they sometimes do, things happened in the milkweeds: [Caroline, please pair up these images below as best as seems reasonable.

Good News!

…Because he/she was trapped by the milkweed flowers and leaves and couldn’t move except forward and backward…

Otherwise it was a mundane mid-day on the Rio with:

Rio Grande, August 24, 20222. Photos by Jim Von Loh.

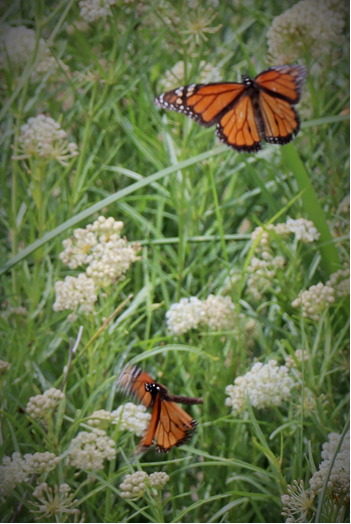

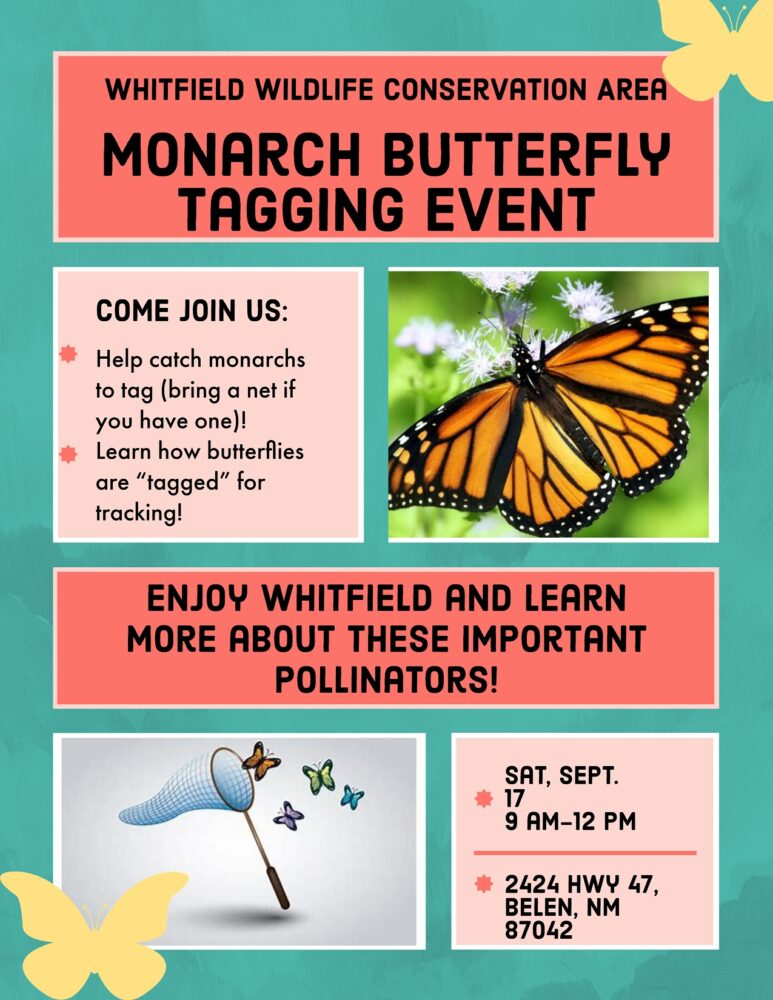

Want to tag monarchs? Their southward autumn migration commences in September. The Valencia Soil & Water conservation District is hosting a tagging event at Whitfield Wildlife Conservation area in Belen (see flyer below). I know from personal experience that Whitfield grows monarchs all summer and they should have plenty of monarchs to tag on September 17th.

Last but not least, we say thank you and a final goodbye to Ray Stanford.

Ray was born December 4, 1939 to Dwight Stanford and Maxine (Harris) Stanford. He grew up in San Diego and attended Stanford University, majoring in mathematics. He then attended medical school at UCLA where he met Katharine (Kit) Doyle. Ray and Kit moved to Denver for Ray’s residency in pathology at the University of Colorado. He practiced pathology at the VA, Webb Waring Lung Institute and Colorado General hospital during his years in Denver, and authored and co-authored numerous papers in the field of lung pathology. In 2007 Ray and Kit moved to Medford, OR to enjoy being closer to family and exploring southern Oregon.

Ray’s passion for the study of butterflies is what many will remember most. His contributions to the field of lepidoptery over the course of his lifetime are significant, including publication of the Atlas of Western USA Butterflies in 1993 and contributor to Butterflies of the Rocky Mountain States by Cliff Ferris and F. Martin Brown in 1980. He is survived by wife Kit Stanford, sister Gail Stevens, children Scott Stanford and Linda Stanford and grandchildren Remi Lathrop, Jolie Lathrop, Alexi Stanford and Dahlia Stanford. Memorial contributions can be made to the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation or the charitable organization of one’s choice.*

* Published by Denver Post on June 19, 2022.

When I moved to Santa Fe in 1980 to begin my professional career, I simultaneously commenced my New Mexico butterflying adventures. I knew no one at the time, but when I began to submit my observations for inclusion in The Lepidopterists Society’s annual “Season Summary,” Ray reached out to me immediately. He was the Season Summary coordinator for the Rocky Mountain region and for many years he was a generous and knowledgeable mentor, guiding me firmly and gently as I learned to identify different species. We also shared an interest in mapping the occurrence of each species, so we regularly shared and debated our geographic data. For several years we made early spring field outings together into southern New Mexico or west Texas to get a jump on the season. In the early 1980s, Ray was a most helpful co-author as we described the ‘Anasazi’ Yuma Skipper. With Ray’s encouragement we initiated Sugarite Canyon State Park’s annual butterfly count, which persists to this day as their Bodacious Butterfly Festival. Ray, you had a huge positive impact and you are very much missed. — Steve Cary

Sad news about Ray! I knew him well from my days in NM (and after), and it was always a pleasure to see him at the Lepidopterists’ Society Annual Meetings. He will be missed.

Great blog, as usual. I was surprised at how many nice butterflies I found near Portales in the mid ’60’s, given the agricultural nature of the surrounding lands. I hope Anisha and Sajan have better luck in the future.