September 17, 2020

By Steve Cary

A Quick Announcement: The Pajarito Environmental Education Center (PEEC) has centralized all “Butterflies of New Mexico” content so it can be accessed here. If you go to that site you can see my blog posts conveniently listed on the right-hand side. The main part of the page is an introduction to “Butterflies of New Mexico,” a completely new and unique online text and photographic resource covering all our 300+ species, which is now available for your use.

In the Introduction, find the list of all the families and subfamilies. Click on any of those to go to your family or subfamily of interest. Within each family or subfamily is a species list and soon you will be able to click on a species to go right to text and images for that species. Currently you can do that for the Swallowtails, Metalmarks and Whites. The other hot links are in-process, and it is a long, tedious process.

My heart-felt thanks go to PEEC, particularly Board Member Jennifer Macke who continues to expertly handle all the webpage design and functionality for the Butterflies of New Mexico project. PEEC staffer Rachel Landman continues to steer me safely through the blogoscape. Katie Bruell guides it all from her perch at the helm of the ship. You three are AWESOME!

How was August for you? For me, the air was so dry it made my skin shrivel, my contact lenses became gritty. The warm night air was so still that not a leaf wiggled. Our traditional Santa Fe style air conditioning could not do the job. I opened all doors and windows after sundown to let the warm air out, but it just hung there in the house, static, unmotivated to move. Rain? Hah! The unofficial rain gauge at my house measured barely 1.42 inches of rain during our usual two-month ‘monsoon’ season of July and August 2020. In my 12 years of record-keeping, that was the smallest monsoon season rain total and 2020 was the only time we received less than 2.00 inches. Most of those other 11 years were not very wet themselves.

Our monsoon season produces the most rain, to which most plants and then butterflies respond, when we have warm, moist air moving into New Mexico from the south. Warm air from over the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of California contains a lot of water vapor. Within that humid air, thunderstorms develop when the sun heats the land surface; warmed air rises (convection) and in the process of rising it cools; if cooling air contains sufficient water vapor, that moisture condenses and becomes rain. Rain makes plants grow. Happy plants make happy herbivores, including butterflies. July and August are the wettest months of our year, producing on average about 30 percent of our annual precipitation total. Coming during the height of the growing season, the monsoon rains are crucial for our ecosystem productivity. They make ‘high season’ for butterflies.

This summer, however, a massive upper level atmospheric high-pressure system parked itself comfortably over the Four Corners region. Stably settled there, that High was a double whammy for butterflyers in New Mexico. First, circulation of air around a High is clockwise, so the air coming our way during July and August was from the Intermountain West and the Great Basin: Nevada, Utah, and western Colorado. That is dry air, my friends, from which it is hard to squeeze precipitation. Second, high pressure stifles convective uplift. Little convection means little cooling, and hence little condensation. Local thunderheads can develop, but they are usually small, do not penetrate high into the atmosphere, and do not cool much. When their scant moisture condenses and falls toward Earth, you can see it trying feebly to rain, but it evaporates before it reaches the ground. Third, air flow from the north creates a headwind for subtropical stray butterflies trying to diffuse northward, like the Dark Buckeyes and Leda Ministreaks we saw back in May and June. Make it a triple whammy. Sheesh.

To deflect my deepening desiccation depression, I hoped to spend August getting a better grip on some of the dotted blues, or buckwheat blues, in the genus Euphilotes. Their buckwheat host plants (Eriogonum; Polygonaceae) are xeric, woody perennial shrubs, so it seemed possible they may be functioning despite dry conditions. In New Mexico, three species are most routinely seen: (1) Rita Blue (Euphilotes rita) has a strong hostplant relationship with Wright’s Buckwheat (Eriogonum wrightii) in southern New Mexico grasslands; (2) Central Blue (Euphilotes centralis) caterpillars eat Antelope Sage (Eriogonum jamesii v. jamesii) in the mountains; and (3) Spalding’s Blue (Euphilotes spaldingi) larvae eat Redroot Buckwheat (Eriogonum racemosum), which grows in pinon-juniper grasslands of north-central New Mexico. If one knows their hostplants, those three blues are relatively easy to discriminate.

There are other species of buckwheat blues whose identities are less clear, at least to me. In our state’s northwest quadrant, wild buckwheats diversify into many species and their buckwheat blue herbivores proliferate into multiple named forms, be they subspecies or other taxonomic entities of uncertain status. I had been through that area — western Sandoval County and eastern McKinley County — back in 2000, honored to have Euphilotes guru Gordon Pratt in tow. We made many stops, I photographed many buckwheat blues, and he graciously told me what they were, so I could label my slides. In the long term, however, those labeled slides did not elevate my understanding to a high level. Looking back today, I saw that I had made a rookie blunder. I took many photos of undersides to contrast and differentiate buckwheat blues from that AcmoLupinoid Blue thingy with all the blue sparklies.

There were at least two different buckwheat blues present in 2000 — ‘Colorado’ Rita Blue and Ellis’ Blue. Gordon helped me label my slides at the time, one versus the other, so I could read the label and ‘know’ what they were. But with my 2020 eyes (that’s the year, not the acuity of my vision), I had a hard time seeing differences between Rita Blue and Ellis’ Blue undersides. Dorsal shots would have been helpful, but I neglected those angles at the time, or they were not on offer, and now I needed them.

What better excuse could there be to vacation in scenic western Sandoval County and eastern McKinley County? In August I made a handful of outings along US 550 from San Ysidro to Cuba, then SR 197 southwest from Cuba; also north from Grants on SR 509 — that’s uranium and coal country. I launched these trips early during the species’ flight seasons so there would be fresh males. I tried to be onsite early in the day so butterflies would be moving slowly and basking dorsally, showing off their uppersides. Eriogonum species readily populate roadcuts, so I drove slowly while scanning for roadside patches of wild buckwheats. When I found a promising buckwheat stand I pulled over, hopped out, and looked for blues on the buckwheat plants because that’s where you find them — on their larval hostplants.

It is nice when a plan comes together! Over the course of those outings I had reasonable success. Most buckwheat stands I encountered seemed a little parched, somewhat reduced in size and vigor, but there were enough blooms to show that life cycles were not entirely interrupted. The desired blues were there, though nowhere common. I had opportunities to get photos of male uppersides and I think I got some respectable ones (see below). Also note Central Blue male (darker blue, wide black submargin, reduced orange on hindwing) for comparison.

I can now distinguish males of ‘Colorado’ Rita Blue from males of Ellis’ Blue by looking at differences at the back of the dorsal hindwing: Ellis’ has a small pink/orange aurora in two cells, while on Rita the aurora covers three or fours cells, plus bold black discs that are missing on Ellis’ Blue. That I also photographed males of the pesky Acmolupinoid Blue made me smile. The next step was to get female uppersides, but on subsequent trips (females emerge later than males) the buckwheats seemed to be senescing early and the blues were very sparse, so I’ll try again in 2021. Meanwhile, I’ve collected buckwheat specimens which former State Botanist Bob Sivinski has agreed to examine for me. Learn the Buckwheat, learn the Buckwheat blue!

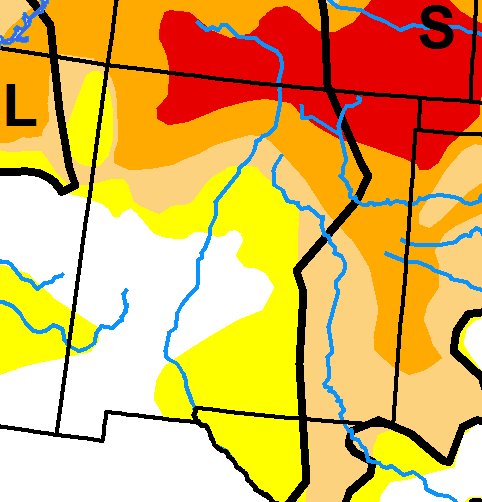

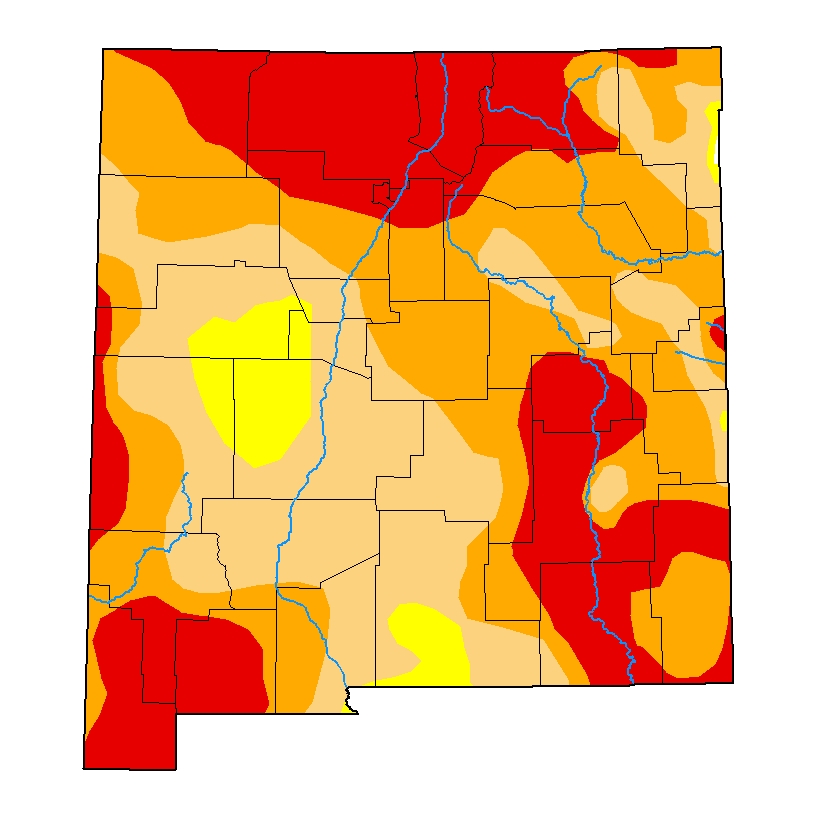

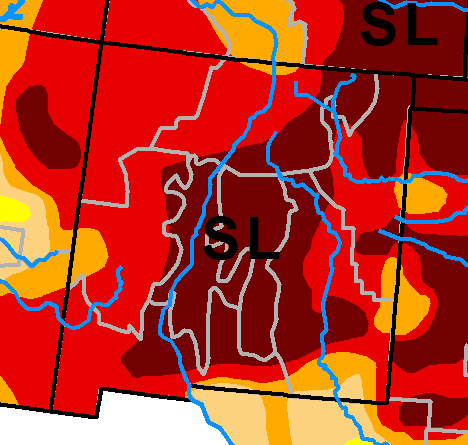

Drought is a major challenge for all life forms including butterflies, so it makes sense for us butterfly hounds to keep one eye on drought conditions, especially if one is inclined to travel for one’s butterfly fix. Few things are worse than driving several hours to your carefully planned destination only to find that conditions are dreadfully dry with few to no butterflies around. To minimize the chance of that happening, I check regularly with the US Drought Monitor. Updated weekly, their maps document changing soil moisture conditions in reasonable detail for the entire country. They depict on-the-ground conditions ranging from wet to normal (white) through abnormally dry (yellow), moderate drought (tan), severe drought (light brown), extreme drought (red), and exceptional drought (dark brown). I consult their maps when deciding where to go, and where not to go, in search of butterflies.

It may not be the degree of drought at any particular time, but the trend, which most strongly influences butterfly abundance in the moment. Plants and insects may be able to detect whether conditions today are better or worse than conditions yesterday, then plan accordingly for tomorrow. US Drought Monitor maps (above) show that while much of New Mexico was drought-free or only a little dry in early June, northern New Mexico was already in “extreme” drought. The map for early September shows that over the summer, “extreme” drought expanded into eastern and southwestern New Mexico. Elaine, who lives in Silver City, said butterflies had become scarce, even though the theoretical butterfly season still has a good two months to go. I have a troubling tendency to look ahead and worry about how bad it could get, but let’s not do that. After all, do you remember the three dry years of 2011, 2012 and 2013? Things have been, and could get, a lot worse. But they also could get better!

Drought may have dire short-term consequences for adult butterflies, but in the long run, drought by itself does not seem to extinguish populations of local native butterflies. Native species seem to be adapted, for the most part, through an ability to remain in developmental diapause (i.e., dormant) during unsuitable conditions, even for multiple years. The best demonstrated of that was by Dr. Jerry Powell at the University of California, Berkeley. He showed that a yucca moth species native to Nevada, Prodoxus y-inversus, can diapause in the pre-pupal stage for as long as 19 years and still remain viable. That seems like a valuable adaptation, potentially allowing it to persist through a multi-year drought.

Anecdotal observations strongly suggest that several New Mexico butterflies may share that ability. Likely examples include spring-flying species such as Spring White, Southwestern Orangetip, Desert Orangetip, and our state butterfly, the New Mexico Hairstreak (aka Sandia Hairstreak, Callophrys mcfarlandi). In the foothills east of Albuquerque, March and April are good times to look for Sandia Hairstreak around stands of Texas Beargrass (Nolina texana), where females look to place eggs on developing flowers, which the caterpillars eat. But don’t go looking for it following a dry winter because odds are the Beargrass won’t be blooming and Hairstreak adults won’t be flying. Why not? Has the butterfly been extirpated by drought? Are they gone from that location for the foreseeable future? No, they persist as diapausing pupae, resting in shallow soils and leaf litter beneath Beargrass plants since pupating the previous May. The Beargrass and their Hairstreak herbivores will postpone their reproductive stages until conditions are more favorable. How many years can they wait? Excellent question!

Thinking about it . . . dormancy is an adaptation all our native plant species must have in order to survive cold winters. They appear dead to the world in winter, then spring back to life in . . . spring. Or their seeds (a state of dormancy) germinate in spring. Our native insects also must survive cold winters, so why would they not have that adaptation? All resident native New Mexico butterflies remain here through winter, but in a dormant state, as egg, larva, pupa, or adult. We think many can remain dormant even longer if unfavorable environmental conditions, such as drought, persist. Experiments to prove it have not been done for each species, but circumstantial evidence certainly makes it seem likely, even necessary. Thus, for many of our butterflies that are scarce or absent during periods of drought, they are still around in immature life stages, waiting until conditions are more favorable before transitioning to adulthood. Here’s hoping for a lush, wet winter.

As I wrap up this drought-focused story, is it any surprise that we received about 0.7 inches of rain at my house this past week? That brings some hope for successful butterfly outings this autumn. September can be a fun time. Here are some suggestions for continued butterfly adventures . . .

* If you typically butterfly in the mountains, try lower elevations near water.

* Southern New Mexico still has many warm weeks ahead.

* Fresh from chrysalids, Painted Ladies seem to be turning up a little more these days. Our understanding of their migration is still in its early stages, so your observations of Painted Ladies can be very helpful. Take photos and post them, with date and location, to online citizen science web sites including BAMONA and iNaturalist.

* September is the best time to look for Apache Skipper (Hesperia woodgatei), one of few late-emerging, single-brooded butterflies in New Mexico. Try hilltops in the broad swath from Silver City northeast to Raton.

Fe, Santa Fe Co., NM; September 11, 2017. (Photo by Steve Cary).

* Monarchs will soon start their long, slow retreat to Mexico (or southern California), which will be experienced in New Mexico in unpredictable numbers from late September through October. Southeast New Mexico sometimes gets thousands passing through in mid-October. Why not reach out to Southwest Monarch Study, get some tags and try to attach some to traveling monarchs? Even if you don’t tag, there is still much to learn about that magnificent species and how it functions in New Mexico and the greater Southwest. Your shared observations contribute to that community learning process.

Stay safe and keep butterflying!

Steve Cary, Santa Fe

Map Usage Statement: The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.