© Steven J. Cary, July 25, 2022

With welcome rains recently falling in much (not all!) of New Mexico, I heard a meteorologist talking on the radio. He said our drought had “begun to ease.” I thought that was a very precisely-worded statement. The drought is not nearly over, and much more rain is clearly needed, but at least the easing has begun. As a result, I expect butterfly populations will “begin to express themselves,” and you can quote me on that. Much more precipitation is needed to get things back to something resembling normal. But also keep in mind, as Elaine Halbedel said to me a few weeks ago, there will be no more “normal” years. We must manage our expectations accordingly.

In the way of announcements:

Someone did me a huge favor by pointing out that the Mourning Cloak larval “carnage” I reported in the previous blog and documented with photos, was very likely the result of synchronized, en masse molting of gregarious larvae from one instar to another. Hatch together, feed together, shed skins together! Makes sense to me. If I could find that email I would offer a more personal “thank you,” but alas . . .

On the plus side of the ledger, Mike Toliver has now finished distribution maps for all the Blues. With Swallowtails, White & Sulphurs, Metalmarks and Coppers previously completed, ONLY the Skippers and Brushfoots remain. One-third down, two-thirds to go. Oof!

“Sierra Grande” is a big name one might expect would be attached to one of New Mexico’s higher peaks. Discovering, then, that it is merely one of numerous volcanic nubs on the shortgrass prairie east of Raton may initially come as a bit of a disappointment. When one digs into the details, however, the disappointment ebbs away.

Sierra Grande is a prominent part of the Raton-Clayton Volcanic Field, which makes that region one of the most curiously unique landscapes in New Mexico. Except for the very highest volcanic necks and mesas along I-25 north of Raton, which touch 9500 feet elevation, Sierra Grande is the next tallest, reaching 8770 ft. Close your eyes and imagine yourself c. 1860, wagoneering westward on the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail, traversing southwest Kansas toward New Mexico Territory. Your prominent landmarks will segue from Black Mesa in far western Oklahoma to Rabbit Ears north of Clayton. Next comes Sierra Grande, which stands as the easternmost summit of its altitude in North America, right there in western Union County, NM. Double-check that if you like.

The highest summits shoulder up through the high shortgrass prairie, up through pinon/juniper woodlands, through ponderosa pine savannas and into windswept subalpine grasslands that typify many of the >8000’ mesas east of Raton. These basalt mesas, stratovolcanoes and cinder cones have been home to three of New Mexico’s most exclusive butterflies: Alberta Arctic, Hobomok Skipper and Raton Mesa Fritillary. As such, they have been on my “got to see” list for at least 35 years. I have visited a few times, but not often enough.

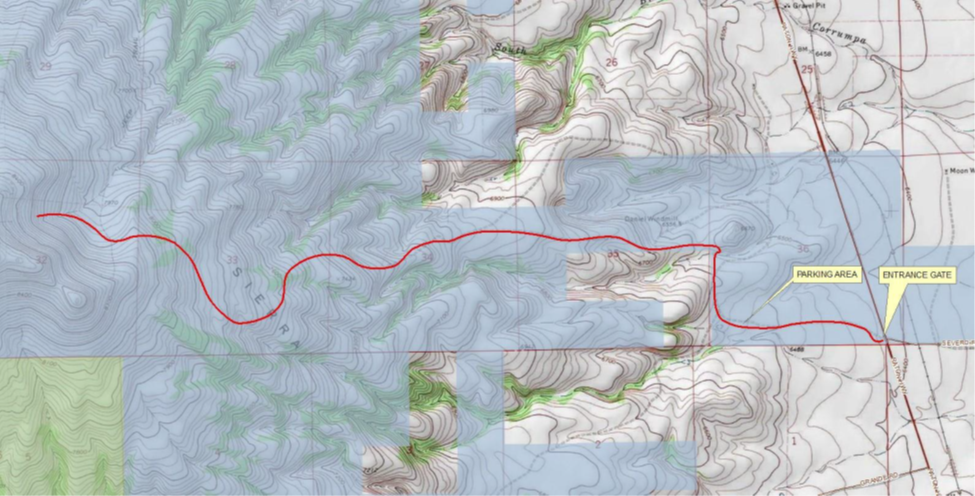

My planned participation in the Bodacious Butterfly Festival at Sugarite Canyon State Park during June 18-19 was a perfect excuse to visit Sierra Grande again. From my house in Santa Fe, the drive to Sierra Grande is three hours to Des Moines via I-25 and US 64, then a few more minutes to curve southeast on US 64 toward the gated (latched, not locked) entrance. New Mexico State Land Office (SLO) owns/manages multiple sections of state trust land in/on/around Sierra Grande. One obtains legal access by purchasing a SLO Recreational Use Permit at this website: https://openforadventure.nmstatelands.org/, which also offers this map (image 1) of the access route.

I probably don’t need to mention that on this mid-June date, prospects for butterflies, or any form of nature, were poor to say the least. Extraordinary drought conditions persisted here, as in much of NM, and the expected steady 30 mph wind would do me no favors either, so I did not have high hopes for a big butterfly day. I find the location quite compelling, nonetheless, and decided to be grateful for whatever Lepidoptera scraps, if any, the mountain would divulge. From the US 64 gate to the summit (image 2) is a straight-line distance of about 5 miles with 2200 feet of elevation gain, but it cannot be walked in a straight line. So, I would get a good hike out of it in any case.

From the gate at US 64, my Toyota Prius traversed a decent dirt road going west for about a half-mile to a designated “camp.” At the ensuing “T” I went right, but the road soon headed uphill and became too gullied for my highway vehicle. I parked the car, donned boots, daypack, and plenty of food and water and began to walk. The route went briefly north and then persistently west on a two-track. Along the way I came over a rise and spooked a small herd of wary pronghorn. After a total of perhaps two miles the road ended at a flat, grassy area backed by fence with a pedestrian gate. Among the few things in bloom were some yellow-flowered prickly-pear cactus, which were visited on occasion by Pahaska Skippers (image 3), and the Pink Vervain visited by the Viereck’s Skipper (image 4). Were they there for nectar or just to get out of the wind?

Passing through that walk-through gate, a hiker is on a gentle, north-facing slope, which has some advantages in a drought; things are not as desiccated as they are on any south-facing slope. There is no obvious trail, but the route to the visible double summit is gently uphill all the way and the treed E-W ridge on my left did a decent job of moderating the southwest wind. It boils down to a grunt of 2 or 3 more miles, through pinon, juniper and grasslands that have been lush and green on my past visits, but not today. There are no real watercourses, but there are a few check dams and dirt tanks excavated into ephemeral drainages. All were bone dry today.

Along the route toward the subalpine grassland that cloaks the summits, the ground surface is largely vegetated and often pleasant to trod. At other times, however, it is littered with volcanic rock debris of motley sizes and shapes. Walking upslope is tolerable because the ground rises to meet one’s step, one can easily see where to put one’s foot, and one can push off with the ball of each foot. Control is good.

On my journey toward the summit I recognized some butterfly nectar plants and host plants, like butterfly bush and leadplant, barely evident above the land surface and barely showing any green. Dormant they were, but ready to go if/when nature called. The most abundant flowers were borne by prickly pear cacti and patches of pink vervain. Butterflies were scarce, as you might expect, but I did record a few species. Melissa Blues and Juniper Hairstreaks were best represented. Also Common Sootywings, instead of the Mexican Sootywings I had hoped for.

Within a mile of the summit, say at 8000’ elevation, the trees fall away and the remainder of the ascent from the east side is on unwooded slopes vegetated in bunchgrasses, forbs and shrubs. One of the dominant grasses is a fescue (Festuca sp.) which has hosted Alberta Arctic (Oeneis alberta capulinensis) here in past years. My hike this day was a week or more past their normal spring flight period; I did not expect to see any, but it was nice to see their host grass in what seemed decent numbers. Some other grass-munchers, below, were a welcome sight.

From there on, unprotected by trees and only partially sheltered by topography, I found myself rather exposed to the wind as I ascended the eastern summit. A few butterflies were functioning near the ground or in the lee of hummocks. On the summit itself, an occasional step by me would trigger a hidden Black Swallowtail to launch from its grassy shelter and into the headwind like the dedicated hilltoppers they are. After two or three valiant windward sorties in the vicinity of the summit, they would trim sail, coast back into the lee of the hill, and settle again in the tawny grass.

I knew how they felt. Did I truly need to reach the higher western summit? No, probably not – just more wind-battered Black Swallowtails anyway. Besides that, I was out-of-shape, tired, tender-footed, and weary of the wind in my ears, so I turned about and walked down into some trees for a seated lunch. Phew! This mountain always leaves a mark on me. On the return trip, I had no choice but to focus on foot placement. With the ground surface curving down and away, each heel met the ground hard. Usually my foot would stay where I put it, but stepping on an unstable rock of odd size and shape opens up a full 360 compass degrees of options; it could roll left or right; frontward or backward; then occasionally, to keep me alert, my foot would stay right where I put it. With 68-year-old ankles and knees adjusting on the fly, I longed for the two-track so I could see where to put my feet.

Having attained the jeep track, I could pay more attention to the butterflies. Once I stumbled (poor choice of words?) on an unusual milkweed that was only about 6” tall and about as bushy around as it was tall – like a pincushion. I saw it because it was green and in full bloom with flowers that were white to pale lavender. Milkweed flowers always pull in butterflies and a closer look revealed two Juniper Hairstreaks (image 6). I think the plant was Asclepias uncialis (aka Dwarf Milkweed, Greene Milkweed, Wheel Milkweed) a small prairie species, but I will defer to any knowledgeable botanist willing to weigh in.

A little farther down the road, the pinon-juniper savanna dropped behind me and I entered the upper edge of a broad grassland. Narrow-leafed Yucca (Yucca glauca), occurred in occasionally dense patches over the next mile of ground and over the adjacent hills and slopes. I was not thinking at all about giant-skippers because I thought the season for Yucca G-S and Strecker’s G-S had passed. But then a female executed a buzzing arc across the road and landed on a yucca flower stalk where it stood out like a flag in a 30-knot wind (image 7). I approached for a photo, but instead spooked her. When she next settled it was down on the lee side of a rock, out of the wind.

Good giant-skipper photos can make a person’s day. They certainly made mine! The overall experience was well worth the effort. Sierra Grande is a spectacular destination in many ways. You should try it sometime. Check out the SLO website first. Then take sturdy footwear.

Sugarite Canyon State Park (SCSP) has had an annual butterfly event for the last 30 years, missing only a COVID year, as best I can recall. Now called the “Bodacious Butterfly Festival,” the event includes butterfly activities not just in SCSP, but also in adjacent Colorado, where Colorado Fish & Game manages the Lake Dorothey and James M. John State Wildlife Areas – many thousands of acres for wildlife-related recreation. Mark Yeager, of Pueblo, Colorado, led excellent walks up there on Sunday and I’m sure they saw great stuff and had good participation. But for purposes of brevity, I will focus this report on the butterfly walks offered on the New Mexico side in SCSP on Saturday June 18th.

The weekend of the events, Sugarite was very dry, like the rest of New Mexico and the Southwest. Grasses, forbs and underbrush were brown and flowerless, for the most part. Trees, including Gambel oak, New Mexico locust, ponderosa pine, pinons pine and various junipers, being deep-rooted, were going about their business, but with less than their usual enthusiasm. North-facing slopes were a little better, even including some nectar and green among the forbs and shrubs. Sites near water seemed less stressed and produced more butterflies, for sure.

The first walk Saturday morning was oversubscribed and so we split into two groups. Optimistically, my group proceeded along the Opportunity Trail, but the sky was overcast from the start. It was nice, personally, to be at a comfortable temperature, but that was not the purpose of the walk. The air, soil and plants never really warmed enough to get the butterflies comfortably active and, as a result, they proved to be few and far between. More impressive to me were the many outstanding butterfly watchers among the participants, including Christopher Rustay (Albuquerque), Elaine Halbedel (Silver City), Kelly Ricks (Des Moines) and Renee Robillard (Corrales). That was just the beginning, because I would later meet others whose photos I had seen on BAMONA or iNaturalist, and I was delighted to be able to connect the people with their images.

Kelly Ricks took the other group that morning. Kelly is a former employee at Sugarite and so she knows the people and they know her. When a group of Girl Scouts was delayed and could not make the start time for my Opportunity Trail walk, Kelly stepped up, waited for the Scouts and then lead them along Chicorica Creek via the Lake Alice Trail to look for butterflies there. That proved fortuitous for the Scouts and also for our butterfly tallies for the day, for they had sunshine. (see image 8)

Kelly elaborates: I moved in slow motion demonstrating the “butterfly walk” for two moms and six kids sporting colorful butterfly face paint. “Butterflies are good at seeing movement,” I said, gradually folding into a low crouch, “if you wanna get close, you have to move really slowly.” The rest joined in. Our stealthy dance must have been quite a sight! We ventured onto the Lake Alice Trail. “Will we see any butterflies with this wind?” asked a mom. Right on cue, a Field Crescent landed nearby. “Remember your butterfly walk!” The kids crept close and the butterfly stayed. By trail’s end we’d glimpsed a boatload of Marine Blues (dubbed “Zebra Marines” by the kids), Hairstreaks, Fritillaries, Admirals…a total of 14 unique species, including a “kissing” pair of Silver-Spotted Skippers (image 9). Most in the group had previously seen only a couple different kinds of butterfly. It’s amazing what a good location, a bit of curiosity, and a skillful butterfly walk can do.

Indeed it is Kelly! thanks for giving the Scouts a day to remember.

My second walk of the day was slated for 1:00 PM along the west side of Lake Maloya. This event was blessed by sunny weather, mild winds, and a diverse group of about 12 participants, from young kids to much older kids, and with a range of skill levels. We saw butterflies from the start and everyone had opportunities to see, touch and learn about butterflies. I was particularly grateful to have other skilled and outgoing people along to share their expertise and help other participants get the most back for their $5.00 State Parks Day Use Pass.

Here are some bodacious photos from butterfly camera-bugs who participated (images 10-14):

When everything was added up for Saturday, I think we tallied 326 individual butterflies and 34 different species. Was anything “abundant?” We counted 113 Marine Blues – not a real shocker – this was Marine Blue Month! Only five species got into double-digits: Marine Blue, Silver-spotted Skipper, Common Sootywing, Two-tailed Swallowtail and Common Roadside-skipper. Nevertheless, the overall numbers far exceeded my drought-despairing expectations. Three things made the difference: (1) having several very capable observers and identifiers, (2) doing three walks in three distinct habitats, and (3) some people did their own walks and saw things no one else saw.

A closer look, however, indicates that many of our 34 species were very minimally represented. Fully half, 17 species, were represented by only one or two individual sightings. That is one effect of the drought: many species are still largely, if not completely, dormant. We New Mexicans go to Sugarite specifically to see some butterflies that aren’t seen elsewhere (mostly) in our state. How did we do on those? We saw only two (2) Hobomok Skippers, only one (1) Aphrodite Fritillary, and zero (0) Raton Mesa Fritillaries. We have higher hopes for next year when it comes to these particular beauties. We hope to see you there next June!

Colorado Hairstreak Life Cycle, text and photographs by Bill Beck

When we want to see a fabulous hairstreak of the mountains, there is nothing better than to rest our eyes on a Colorado Hairstreak (image15) basking with its wings open; displaying its royal purple “cloak”. While it’s the state butterfly of Colorado, it is not uncommon in New Mexico! Its host plant is known to be Gambel Oak, which is certainly one of New Mexico’s common oaks of the mountains.

Being quite the “stunner” hairstreak butterfly in both colors and large size, I’ve been raising them for a couple years, and have raised them from egg to adult. Like the other hairstreaks associated with oaks, the Colorado lays its eggs on the oak twig joints, and it overwinters there. Then, in the spring, the eggs hatch just as new oak growth starts.

The Colorado Hairstreak is different than all other hairstreaks in New Mexico in that it is NOT in the same butterfly TRIBE!!!! All the rest of the hairstreaks are from the tribe Eumaeni, which originated and evolved mostly in the neotropics in Central and South America. However, the Colorado Hairstreak is a member of the Theclini tribe, which has originated and evolved, for the most part, in southeast Asia. It has many relatives there and you can see the similarities if you look at their hairstreaks. It is believed that the Colorado (and the other US Theclini, the Golden Hairstreak) migrated from the Asian continent over the Bering land bridge in a different time and climate. Now that’s interesting!

Starting with a female caged with oak branches is a way to get eggs if you want to try. Other folks sometimes go looking for the eggs themselves on branch twigs, especially in the fall after the leaves fall off. The eggs are vastly different than Banded or Oak hairstreak eggs and are really spectacular in shape….wouldn’t you say a white “sea urchin”? (image 16)

When the eggs hatch you can again definitely tell they are not a Banded or Oak. The cats are somewhat long and grey, with perhaps fewer or shorter hairs (setae) (image 17). They grow quickly through their instars. One time I’ve had them eat only young leaves. The last time I provided a choice of Gambel Oak flower catkins and leaves, and they preferred the catkins.

As you can see, they continue to be on the long side, and turn quite silvery green, matching the early Gambel Oak foliage. (images 18 and 19)

After a couple weeks of eating and with growth completed, the caterpillar picks a spot, changes into a pre-pupa and then with another skin molt, the pupa. (images 20, 21 and 22)

The pupa of course transforms inside to the adult butterfly. It’s very cool that you can see this change happen, and the Colorado Hairstreak pupal skin becomes translucent just before eclosion. (image 23)

And so the completely formed adult emerges, unfolds and dries its wings, and is ready for the circle of life to start again! (images24 and 25)

Bill Beck, I learn something from every month! We all thank you for explaining how butterflies, especially hairstreaks, work.

White-lined Sphinx. Last month it was Marine Blues. This month, El Paso naturalists Tom Gill and Leah Whigham were on the front lines of the exploding populations of White-lined Sphinxes (Image 26), which responded rapidly to the early monsoon rains. They reached out to me after the July 4th weekend and within a couple of days New Mexico’s own CJ Goin made the first photo report from Las Cruces.

Now, of course, and over the last couple of weeks, White-lined Sphinxes have exploded over much of New Mexico. For a couple of weeks, Marcy and I gently waded through them during our dawn and dusk walks (avoiding the heat of the day), when they flocked to whatever flowers were blooming in the neighborhood. Based on CJ’s image below (image 27), we will see them again some day!

While we are thinking of moths, take a look at Marta Reece’s image below (image 28) of a mated pair of Polyphemus Moths (I confess I am not certain which species of Polyphemus). Marta measured their wingspan as 4.5 inches – clearly one of our largest moths. Can you tell which is the male and which the female? Here’s a clue: unlike butterflies, which are primarily visual creatures, moths find their mates by use of scented pheromones. The female emits the scented particles and it is up to the male to detect the scent and follow it back to the female. Scent detection is initiated in the antennae of the male. Now look again at the image; one individual has antennae that are barely noticeable, while antennae of the other are at what one might call “full attention.” This photo certainly won my attention.

Despite our drought/desertification/aridification – whatever you want to call it – you all are out there seeing stuff. Do not be deterred by weather forecasts or climate doom and gloom. There will always be butterflies to be seen, so you might as well go out and see them!

I believe your narrow leaf yucca on sierra grande was probably Yucca glauca. Thanks for the directions to go there, I’ve always wanted to & haven’t been yet.

right you are Lisa. thanks for catching that. I made a quick fix, so maybe no one else will notice :^)

I don’t think there is any way that the Nortern Crescent photo is that species, must be somebody else, like a Field C?

i would be anxious to see the acmon (texana) and lupini maps for review and comment.

Paul Opler

Hi Paul, and thanks for weighing in. I wobbled on the crescent, but am happy to defer to more experienced eyes. It has been changed to Field Crescent in the post. As for Lupine and Acmon blues, I (Mike Toliver, too, I think) continue to wander blindly and look for some phenotypic handholds. We recently opted to call everything in NM Lupine Blue, as you can see here: https://peecnature.org/butterflies-of-new-mexico/blues-lycaenidae-polyommatinae/#acmon. We still can’t reliably tell one from another, but this seemed to be the way the collective taxonomic wind was blowing, so we got on-board, so to speak. Is there a recent publication that we should be studying? We would greatly appreciate your expertise. Do we have Acmon Blues in NM? If so, where? I am expecting that most photos will not be sufficient to differentiate one from the other, but I would be only to happy to be wrong.

Steve! I am a big fan of Hairstreaks. So amazed at Bill Beck’s fabulous pictures and they migrated from Asia is amazing! Your blogs are eye openers for me.

Selvi

Selvi, your thoughts and comments are most welcome, as always. migrating from Asia quite some time ago, but it seems happy here, thank goodness!

Another extraordinary blog packed with information and excellent images – thanks, Steve!! Your stories of places and butterfly encounters make it easy to put oneself onto those landscapes and I appreciate them for the resulting “visuals”.

The youngsters with butterfly eye art look very happy and proud to be a part of the event – kudos to the artist! I’m always happy to see Bill’s reports and images, the CO hairstreak was perfectly-timed as we saw one last week near Cloudcroft, snapped several images of it on a muddy area, but just barely saw the bright blue dorsal color when it flew to another part of the puddle. Amazing to see Bill’s image!

Your discussion of butterfly diversity versus numbers of individuals parallels the southern trend as well (IMO), through early July. Currently, the diversity here is on the rise as is the number of individuals per species. I’m hopeful that moderate-to-heavy and consistent monsoon rainfall will arrive soon to increase the nectaring/puddling/etc. opportunities!!

many thanks, Jim, for your kind remarks. fingers crossed the monsoons do right by you all in Dona Ana County!

I and my son Jeremy attacked Sierra Grande on May 28, 1993…our quest was to find Oeneis alberta capulinensis. We accessed the peak from the east which I was directed to as the public access point when I inquired locally at a nearby ranch outside of Des Moines on the north side of the mountain. This was one of the most grueling hikes I have made. It sounds like Steve’s point of attack may have been easier but longer. All of the small rock on the hillside makes for a arduous, constant ankle-beater. And the wind never quits blowing up above the trees. We got our objective but we were beat when we arrived back at our vehicle. I estimate it was about a 5-6 miles round-trip trek. A great place to explore…once…but not going back. Sierra Grande certainly beat me up!

Mike, thanks for the perspective of time, and youth! :^) it is nice to that “I did it” and don’t have to do it again. but still . . . am I ready to give it up?