By Ruth H. Lier

It’s spring! While that means longer days and warmer temperatures, it also means it’s time for the arrival of pollen from many trees, flowers, and grasses.

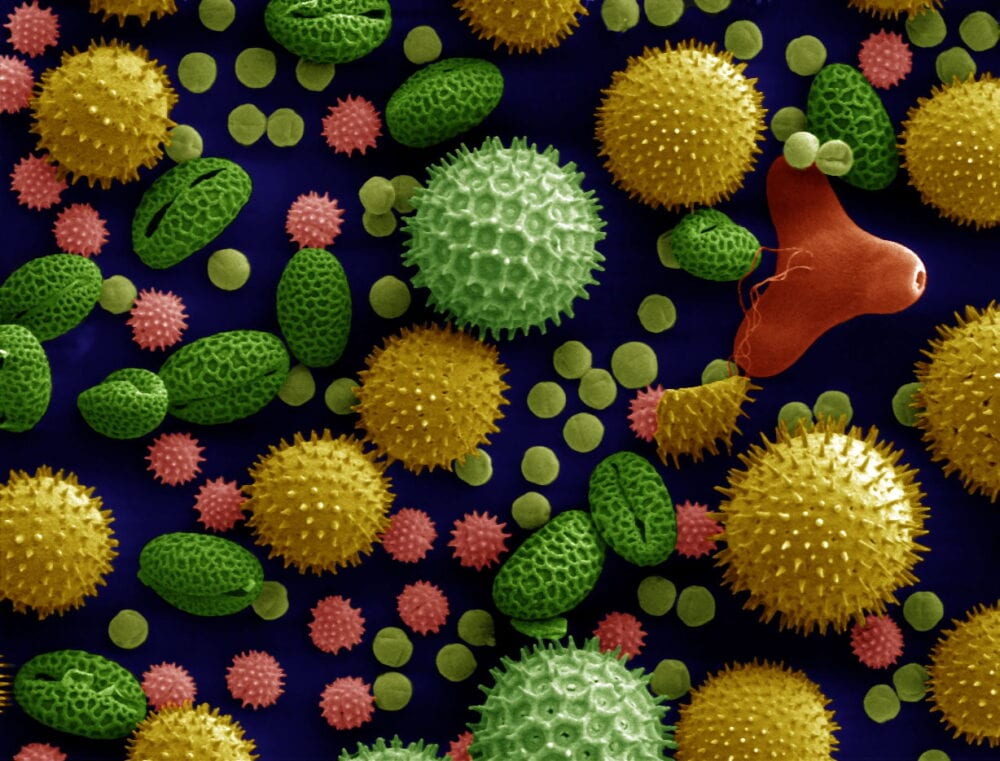

Because pollen grains are so small, we can’t usually see them blowing in the wind, traveling up our noses or into our eyes, and clinging to our clothing. This unseen world of pollen can cause us to itch, have red eyes, sneeze, or bring about more severe reactions.

Pollen grains usually range from 3 to 30 microns in size. A micron is one millionth of a meter, so they are very tiny! When pollen grains are viewed under a microscope, their size and shapes are used to identify their genus and species. Pollen grains can be round, oval-shaped, triangular, or have air bladders and look like Mickey Mouse heads. They may have bumps, barbs, and spines, or they can have golf ball depressions and furrows. They can be white, cream, or yellow in color.

Juniper Pollen:

Juniper pollen is a particular enemy of those with allergies in New Mexico! The male trees usually start to release pollen as early as December, but pollen levels peak in March and April.

The pollen from junipers is known to travel 200 miles on a moderately windy day! When viewed under a microscope, we can see that juniper is a spiny pollen. So when it goes up your sinuses or into your eyes, it is especially irritating and hangs on.

Piñon and juniper trees also make up the majority of New Mexico’s forests — so junipers have power in numbers. According to an inventory from the New Mexico Department of Agriculture, 60% of our forest lands are made up of piñon and juniper trees.

How Scientists Use Pollen:

Pollen is not just an irritant, however. Scientists can use pollen as a window into the past.

We can see how our forests have changed over time by taking a look at the pollen amounts found in soil cores. Predominant forest species can change through the years due to climatic changes from fires, temperature changes, rainfall amounts, insects, and other diseases. Decreases or increases in pollen amounts found in soil are indicative of changes in plant populations. Learn what the pollen found in a core sample taken from the Valle Grande tells us about the past climate cycles in the Valles Caldera.

Pollen analysis can also be used to identify artifacts. National Parks use pollen analysts to date artifacts or ancient ruins. Pollen analysis has been used to date many artifacts, such as Ötzi the Iceman, a natural mummy that was preserved in ice in the Italian Alps until it was found in 1991. The pollen in his gut was studied to identify where his last meals were eaten.

Take a walk in the forest today and consider the history underneath your feet, thanks to pollens!