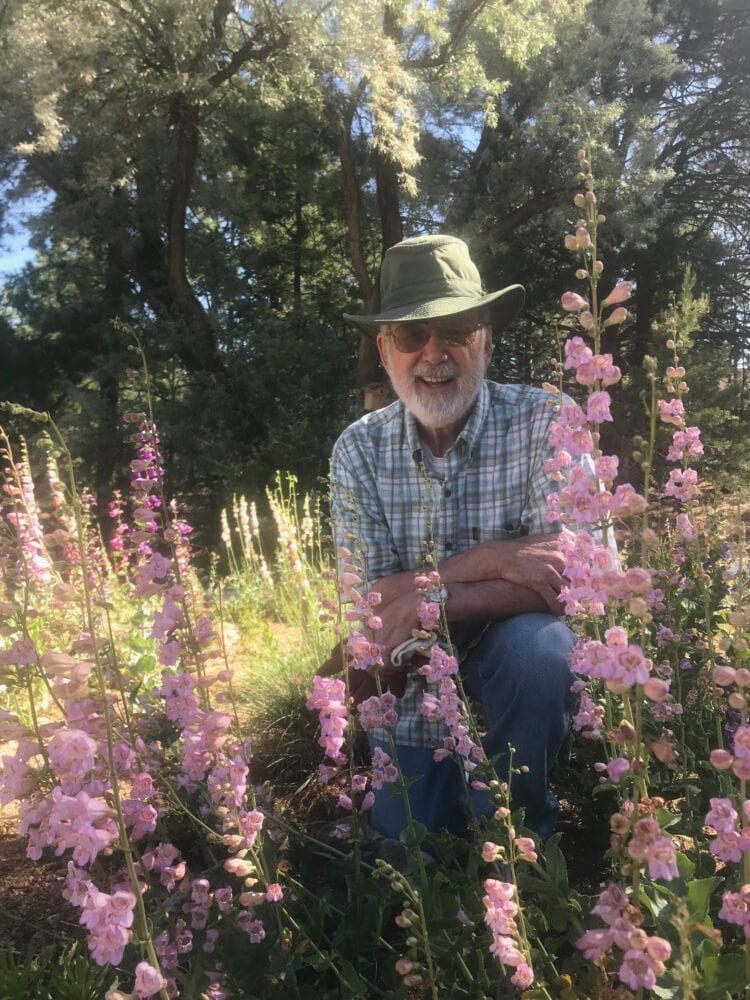

Larry Deaven, a PEEC volunteer, has been growing penstemons for over 40 years. Fortunately for our community, he began gardening for PEEC at the nature center in 2015. He received a special projects grant from the American Penstemon Society in 2016 to help support garden construction. The penstemon gardens at the nature center now contain over 2,000 plants including representatives from 100 different species and upwards of 60 subspecies, color forms, or hybrids.

We hope you enjoy reading about PEEC volunteer Larry Deaven and how he created our spectacular penstemon gardens.

Deaven worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory in human cytogenetics and human molecular genetics until he retired as the Director of the Center for Human Genome Studies in 2003. Although his primary education was in mammalian cell genetics, he also studied plant genetics, botany, and horticulture before coming to Los Alamos in 1971.

Deaven also received the highest honor bestowed by the Laboratory. Earlier this year, Los Alamos National Laboratory awarded four former researchers the Los Alamos Medal for their scientific contributions. Deaven, along with Scott Cram, Robert Moyzis and Howard Menlove received the award. The team of Deaven, Cram, and Moyzis were recognized for their work and unprecedented accomplishments sequencing the human genome and Menlove for his work on methods and instruments used for treaty verification.

PEEC: What brought you to Los Alamos?

L.D.: I was a student at MD Anderson Hospital in Houston when someone from LANL came and gave a seminar about a new kind of equipment developed at LANL. He discussed how they could measure the DNA in cells very rapidly with this new equipment. I was interested in using the device for research I was doing; looking at chromosomal changes that accompany malignancy and trying to determine if chromosomal changes occurred as the result of malignancy or if they were the cause of malignancy. The machine at LANL, called a flow cytometer, was an instrument that could measure the DNA in each cell by sending a population of fluorescently-dyed cells in suspension across a laser beam. The cells give off a burst of light and you can measure the intensity of the light. These measurements tell you how much DNA is in the cell. We could rapidly measure the DNA in each cell at speeds of 6000 to 10,000 cells per second. I came to LANL as a postdoc in 1971 for this reason. I instantly knew I loved Los Alamos and the beautiful environment here. Luckily a job came available and I stayed.

PEEC: Where did you grow up?

L.D.: I’m from Central PA, near Harrisburg. I still have some family in PA.

PEEC: Tell me about your education and background.

L.D.: I have a Bachelors Degree in Zoology, Masters in Genetics, and Ph.D. in Biomedical Sciences through a special graduate school that was making an effort to bridge the gap between M.D.’s and Ph.D.’s in medical research.

PEEC: How did you become interested in genetics and can you tell us more about your career?

L.D.: Like most undergraduates in the life sciences, I took a course in general genetics. I knew genetics was a quantitative side of biology, which I found intriguing. At that time, most of biology was descriptive. Genetics had something you could sink your teeth into and I was attracted to it. I ended up staying there (Penn State) for my master’s degree. During my master’s program, I worked with a professor who discovered some major blood groups in trout. He wanted to use these blood groups to analyze wild fish populations. His goal was to gain information on what their genetic heritage had been and what happens when you stock hatchery trout in streams with wild fish. After my master’s degree in genetics, I worked in cellular genetics at M D Anderson Hospital. It was there where I became interested in chromosomal changes. I was trained in mammalian cytogenetics; the study of chromosome and chromosomal changes in cells.

When I first came to LANL I worked with laboratory employees who had been involved in radiation accidents, some of the early accidents at the lab when people were exposed to high doses of radiation. Some of these people were still living, and I worked with them to determine the extent of cellular damage they had sustained. When someone was exposed to large doses of radiation it damaged the DNA in the primordial cells in their bone marrow. They continued to generate daughter cells that had chromosomal damage. Up to 40 years after exposure I could do a chromosomal analysis and get information on the type and quantity of exposure they received. I then spent 3 years in DC working at the Department of Energy managing their genetics programs. This was in the early 80s when molecular cloning was being developed. When I returned to LANL in 1983, I reflected on how we have flow instruments that can measure DNA in single cells and on the possibility of combining flow cytometry with colecular cloning. I wondered if we could stain isolated human chromosomes and sort them into individual fractions using flow cytometers which had by that time been developed into flow sorters. We soon found out that it was possible to sort hundreds of thousands of copies of each of the human chromosomes. Using molecular cloning techniques, the DNA in these sorted chromosomes could then be used to make DNA libraries that represented the genes in each of the human chromosomes. The DNA libraries were shared with investigators throughout the world and were used to find the physical location of the genes on each of the human chromosomes. Later the fragments of DNA in the libraries were sequenced, and these DNA sequences became the beginning of the Human Genome Project. Working on that project became the rest of my career.

PEEC: How has your scientific background helped you as a gardener?

L.D.: Thoroughness and attention to detail are very helpful as a scientist and gardener. In life science, there can be five trials of the same experiment. You may not always get the same results. It’s the same with gardening.

PEEC: How did you get involved with PEEC?

L.D.: I know Chick Keller, one of the founders of PEEC. Years ago he introduced me to PEEC and their wildflower walks. When PEEC moved into the county building, Chick encouraged me to get involved with the gardens. I’ve been familiar with penstemon flowers for 25-30 years, maybe even longer, so one of my first ideas for a PEEC garden was one featuring penstemons. I was always impressed with penstemons; they’re drought tolerant and have a unique beauty in having rich and vibrant colors. I decided I would like to plant a demonstration garden so people could see what the possibilities are with penstemons.

L.D.: I’m so happy to hear that! Wow. It’s exactly what I wanted to do; get people to see these flowers, their beauty, and know they can do something like this in their own yard.

PEEC: If you had advice for anyone that wanted to start their own penstemon garden at home, what are the pointers you would share?

note: Larry and nine other PEEC volunteers spent endless hours collecting dry penstemon plants at the nature center, cracking seed pods and sorting seeds. PEEC’s own penstemon seeds are now on sale in the nature center gift shop.

L.D.: My experience with commercial greenhouse growers is that they want to grow large, flowering plants that will attract buyers. They grow them in pots and the roots are rather compacted. It can be difficult to get the compacted root balls to grow and spread naturally. For penstemons, I much prefer to grow new plants from seeds and plant them into permanent locations when they are small plants with their first 10 to 12 leaves.

Growing from seeds can take a long time or it requires some steps to speed things up. The seeds, like many desert plants, have germination inhibitors. If you were to just plant the seeds in a pot, they could sit there in the soil for up to five years and not germinate. The seeds need cold and damp conditions simultaneously to germinate. What I do is put the seeds between damp paper towels in a plastic petri dish in my refrigerator. Once the seeds germinate in the fridge I plant them. I’ve written some lengthy instructions that are given to people when they buy the PEEC penstemon seeds. I would urge gardeners to read the directions prior to planting.

PEEC: You put in so many volunteer hours. I would say you average 120-150 hours a month! What keeps you going? What do you feel when you’re gardening?

L.D.: For me, it’s a form of meditation. It’s hard to describe if you haven’t meditated. When I really get into gardening, when I’m really into it, my mind clears and that’s the most wonderful thing. SO for me, gardening is Zen. It’s meditative.

-If you are interested in learning more about our volunteer program, please email Christa Tyson at visitorservices@peecnature.org.

Article by Christa Tyson, PEEC Visitor Services Manager

Inspiring on so many levels! I am bringing PEEC pestemon seeds to grow in Placitas and will follow directions to the “T”. Thank you for everything PEEC and its volunteers do.

It was terrific to read about Larry’s career and see how it fits with his penstemon passion. And the comment about gardening as meditation strikes home–I think all of us who love nature find that truth.