By Aimee Slaughter, Museum Educator, Los Alamos Historical Society

How did people in the Pajarito Plateau’s past get their water? How did they live in a dry environment like ours?

Ancestral Pueblo people who lived here hundreds of years ago used ingenious dryland farming techniques, and homesteading farmers at the turn of the twentieth century also conserved water for their farms and families. The Los Alamos Ranch School had to provide water for students, staff, and animals at the school. When the Manhattan Project took over the area, a rapidly growing population strained infrastructure, and providing enough water to homes was a constant concern. For hundreds of years, people have solved the challenges of finding water in a dry environment and have created diverse and vibrant communities here on the Pajarito Plateau.

Ancestral Pueblo people began to create communities here about 900 years ago and lived here for around 400 years before moving on. They were farmers, and our flat mesas provided good locations for farms. Ancestral Pueblo people needed to be clever to make the best use of the little water available. They created terraced farms, which allowed water to run from higher plots to lower ones, making sure little water was wasted.

They also built waffle gardens, small square plots surrounded by low earthen walls arranged in a waffle-like grid. The small berms of dirt around each plot helped to contain the water in the farm. Drought may have contributed to the Ancestral Pueblo people’s decision to move in the early 1500s, and the pueblos they founded — including Cochiti Pueblo and San Ildefonso — are close to the Rio Grande.

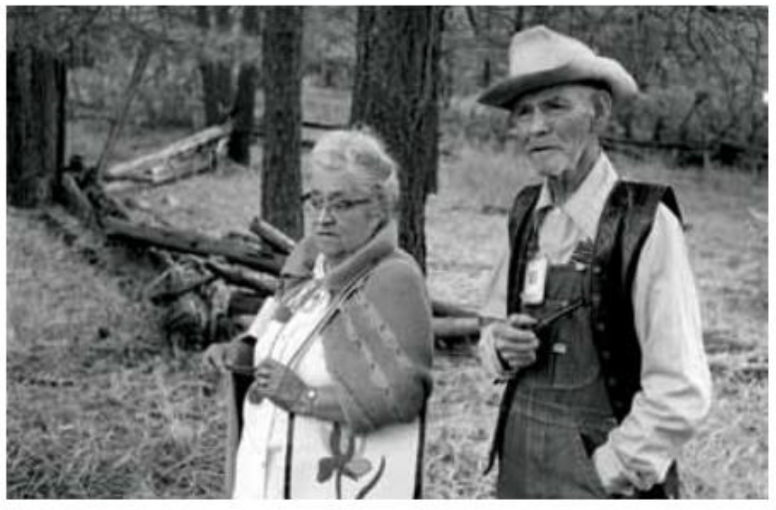

Beginning in the late 1880s, homesteaders claimed land on the plateau for farms. A few homesteaders were Anglos who came west to make a living, but most were Hispano farmers who had lived in the Española Valley for generations. These homesteaders also used dryland farming techniques and conserved water to make sure their crops, animals, and families had what they needed.

In 1917, the homesteaders had a new neighbor: the Los Alamos Ranch School. An elite college prep school for young men, the Ranch School was centered on outdoor activities and needed water for its gardens, crops, livestock, and horses, as well as students and staff. The large wooden buildings like Fuller Lodge also needed a large supply of water in case of fire.

To provide this emergency water supply, as well as a place for fishing, boating, swimming, and ice skating in the wintertime, the Ranch School enlarged a pond in the center of the campus and named it after the school’s founder, Ashley Pond, Jr. To keep Ashley Pond filled with water, and to provide a reliable source of water for the school, students and staff built a dam in Los Alamos Canyon. The water from the dam flowed to the school in gravity-fed pipes.

When the Manhattan Project arrived on our mesa, evicting the homesteaders and the Ranch School, water presented an even greater challenge. The army post of 1,500 residents quickly grew to over 3,000 people by the end of 1943 — and to over 8,000 people by the end of 1945. The wartime community became used to the reality that faucets would not always produce water when turned on. The army urged conservation. Crisis struck the winter after the war’s end, when the pipes from Guaje Canyon and Los Alamos Canyon froze and no water was available for the town. Residents were encouraged to leave if they could, and water was trucked in from the Rio Grande.

The ways that we’ve solved the challenges of getting enough water have changed with time, but what hasn’t changed is our need for water for our families, our gardens, and our pets. Visiting Bandelier to see waffle gardens or thinking about students at the Ranch School when you’re at Ashley Pond can help us to connect with the people who lived here in the past.

To learn more about historic uses of water on our plateau and about the history of Los Alamos, visit the Los Alamos Historical Society online at @LosAlamosHistory on Facebook and Instagram and at www.losalamoshistory.org.